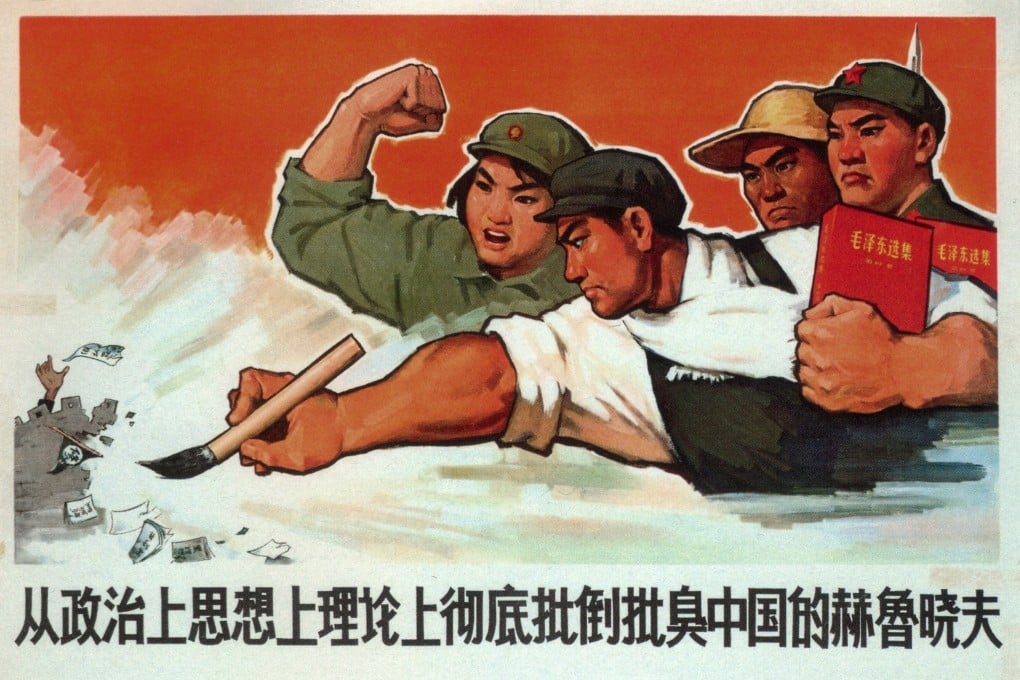

How art spread Maoism around the world, from China all the way to Peru

An excerpt from Art, Global Maoism and the Chinese Cultural Revolution, edited by Jacopo Galimberti, Noemi de Haro García and Victoria H. F. Scott, explores the contradictions inherent in the global spread of China’s 20th century political doctrine

“Contradiction is present in the process of development of all things; it permeates the process of development of each thing from beginning to end.”

Mao Zedong, ‘On Contradiction’, 1937

Art and images were and continue to be central channels for the transnational circulation and reception of Maoism. Though it is rarely acknowledged as such, the so-called Great Chinese Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was one the most extraordinary political upheavals of the 20th century. And similarly, no other post-war statesman has elicited more conflicted emotions than Mao.

If the 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of anti-colonial struggles, and “an awakening sense of global possibility, of a different future”, this should also be ascribed to Maoism. Thus it comes as no surprise that Fredric Jameson viewed Maoism, rightly or wrongly, as “the richest of all the great new ideologies of the 1960s”, when the idea of “Maoist China” became a productive epistemological device to reimagine the world, to reinterpret its hierarchies and to act to change them.