Shoko Asahara: my memories of how Tokyo subway sarin attack spread terror one day in March 1995

Post journalist Charmaine Chan recalls the fear that gripped Tokyo residents, glued to their TVs in a pre-internet age as police hunted for Aum Shinrikyo cult members in the weeks after deadly gas attack

One of the worst aspects of my newspaper job in Tokyo was the bird-call starts. To be at my desk by 6.30am meant catching a 5.30am train and changing lines twice to reach the Asahi Shimbun headquarters in Tsukiji. March 20, 1995, however, changed my attitude to the early shift.

That day, during peak-hour Monday morning traffic, members of the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult gassed the city’s subway system, killing 13 people and injuring thousands more.

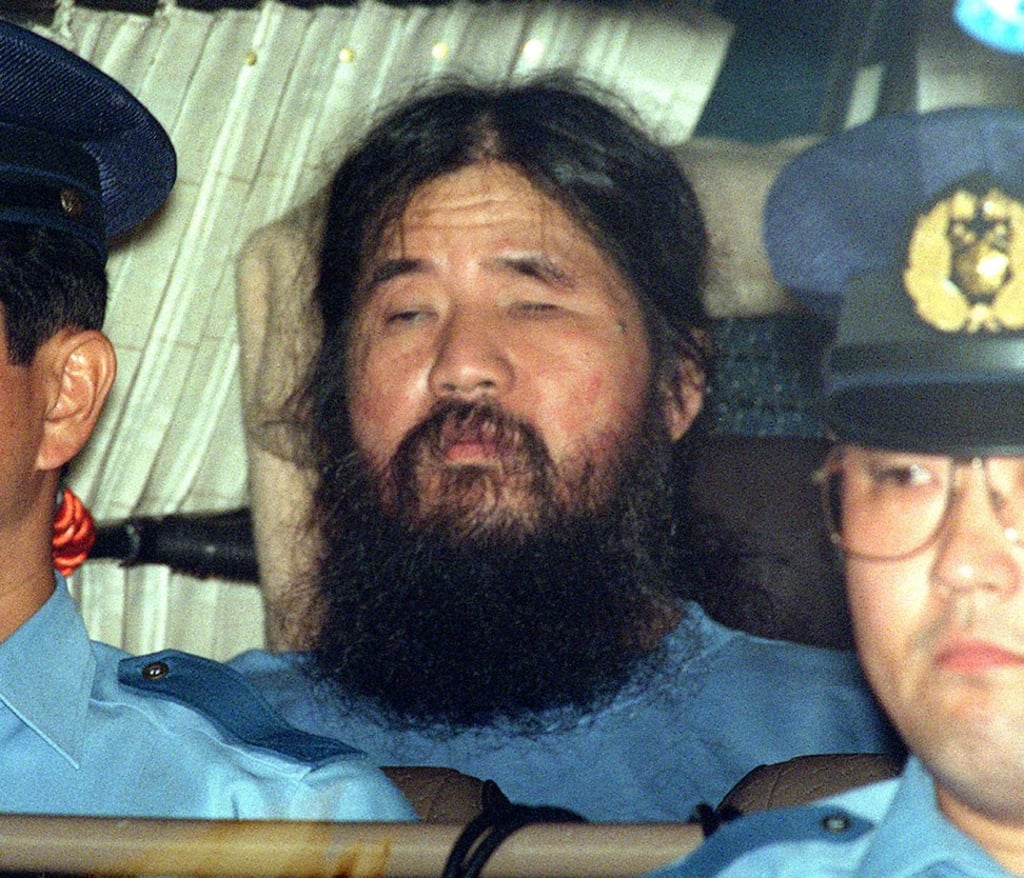

The media provided near round-the-clock reports, culminating in the capture of the corpulent, near-blind, self-proclaimed guru. On May 16, 1995, police discovered him in a coffin-like cell at the group’s headquarters in Kamikuishiki, a hamlet at the foot of Mount Fuji. Television cameras on that misty morning broadcast scenes few would forget: a couple of hours after the day’s drama began, the countdown to finding Asahara started with reporters gasping: “The doors are being forced open,” then shrieking into microphones as his location was confirmed.

An unkempt Asahara, dressed in pink robes, was ejected from his hideout still hugging wads of Japanese yen, and driven away in a blue van at 10.35am. With helicopters buzzing overhead, hundreds of reporters giving chase and crowds perched on highway overpasses watching the spectacle, it recalled the surreal tailing of O.J. Simpson a year earlier on a Los Angeles freeway. Only this was Japan, known for its law-abiding citizens and often ridiculed for instilling in them an unshakeable will to conform.