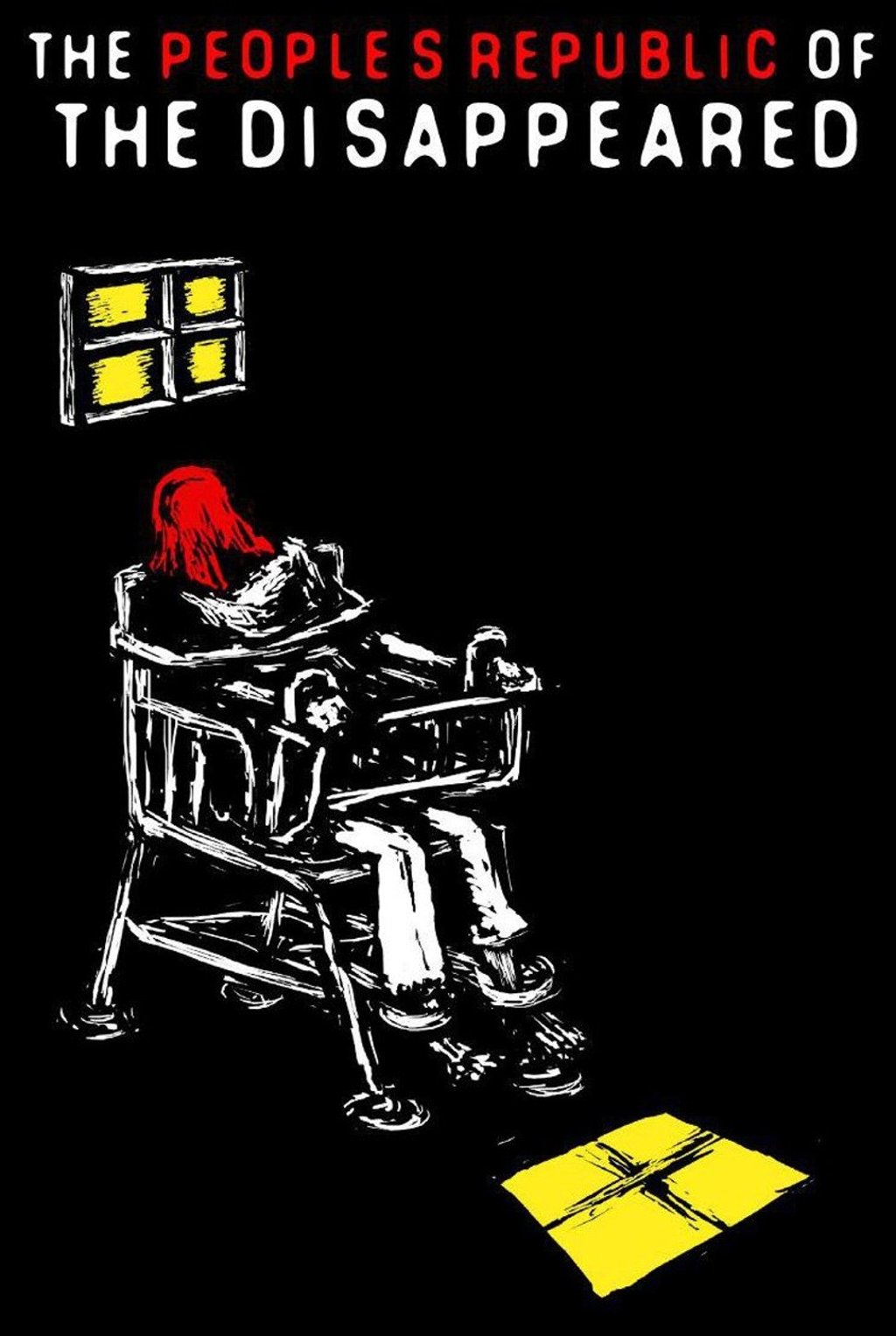

Abductions by Chinese authorities detailed in US-published book

The People’s Republic of the Disappeared documents the brutal techniques used on civilians and rights activists under the state’s ‘residential surveillance at a designated location’ detention order

“Residential surveillance at a designated location” doesn’t sound so bad. It hints at house arrest, the sort of detention you might get if your transgression doesn’t warrant a prison sentence or perhaps while the authorities determine the nature of your crime. But if those who have provided first-hand accounts in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared are to be believed, it is far more sinister than that.

Published in November, the book is edited by Michael Caster, a human rights advocate and senior adviser to the Chinese Urgent Action Working Group, which states its mission as being to strengthen the rule of law in China. The book brings together the accounts of 12 people who have been held under RSDL, a form of detention introduced into Chinese criminal law in 2012, with the amendment of Article 73 of the Criminal Procedure Law, to allow the authorities to detain people for reasons of state security or terrorism.

Sui’s account comes towards the end of the book, by which time the reader is familiar with RSDL, which, it is alleged, typically begins with an abduction and quickly descends into physical and psychological abuse, isolation, threats to family and friends and sleep deprivation.

“Early on the fifth or sixth morning of sleep deprivation, the tiredness started to hit me. My consciousness felt vague, followed by a pain I felt all over my body. It was like being roasted by a fire, while at the same time feeling extremely cold. It was a kind of pain that I had never experienced before. Faintly, I felt that I was dying,” writes Sui, who is known for his work defending other rights activists, including fellow lawyer Guo Feixiong.

I had the right to ask for a lawyer, but I did not have the right to receive a lawyer. I had the right to meet embassy personnel, but the authorities could make me wait as long as they wanted before allowing me to meet anyone