Then & now: Blowing their trumpet

Elaborate, lavish funerals prove that 'face' is as important in death as it is in life, writes Jason Wordie

Funeral rituals are a part of life; throughout human history, every culture has marked this most final of journeys in its own way.

The Chinese approach to death has always been very distinctive. Various historical travel accounts, documenting aspects of life in the mainland, Hong Kong and among the overseas Chinese diaspora, describe these events.

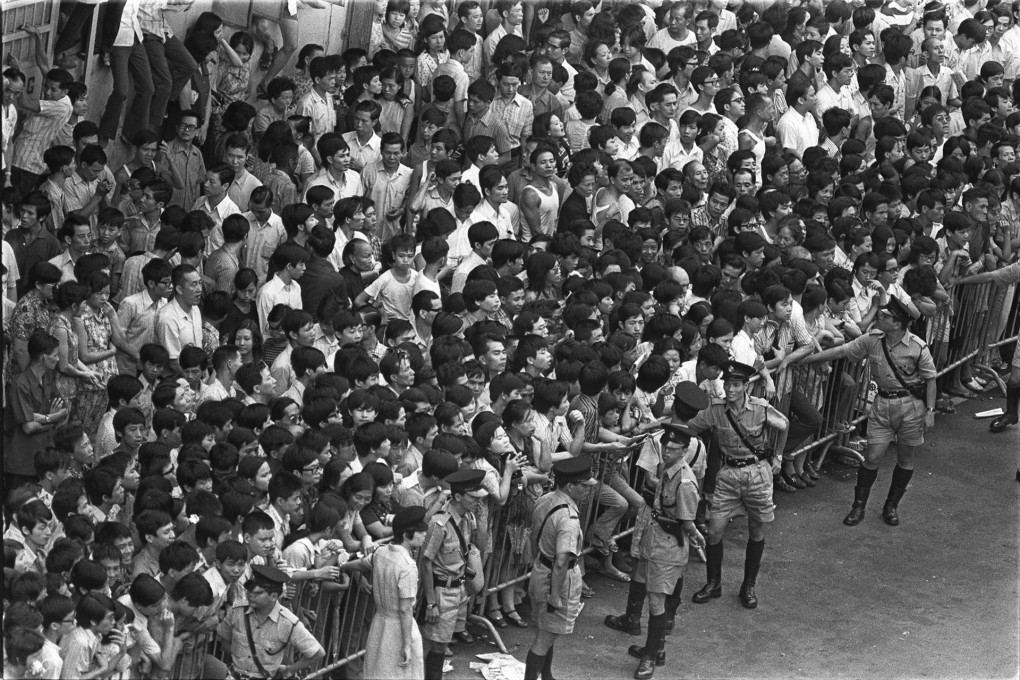

In the 1950s, funeral processions for the wealthy and socially prominent could stop traffic across an entire city for hours. Like any unusual, colourful event, details of the cavalcade would be pored over by onlookers for days afterwards.

In both villages and cities, musicians have long accompanied the Chinese dead to their graves. While the clashing of cymbals and wailing of flutes were standard escorts to the land of shades for poor and wealthy alike, by the late 19th century a new innovation had come into vogue in the Chinese world - the European-style brass band.

Hong Kong, and other foreign-influenced cities in China, such as Shanghai and Tientsin, had plenty of nightclubs, whose freelance musicians were always prepared to work an extra gig - especially well-paid daytime numbers that didn't conflict with their evening routine. British military bands could be obtained for a price (the Hong Kong Police Band can still be hired for various occasions); even the Salvation Army was not above renting out its band for "heathen" funeral ceremonials, if the fee was acceptable. Onward, Christian Soldiers - perhaps unsurprisingly - was the usual theme tune this particular ensemble played.

As with much else in Chinese life, if something is good, then more of the same must naturally be better. Having two or more full brass bands marching along in the cortege, each playing a different tune, was a commonplace feature.