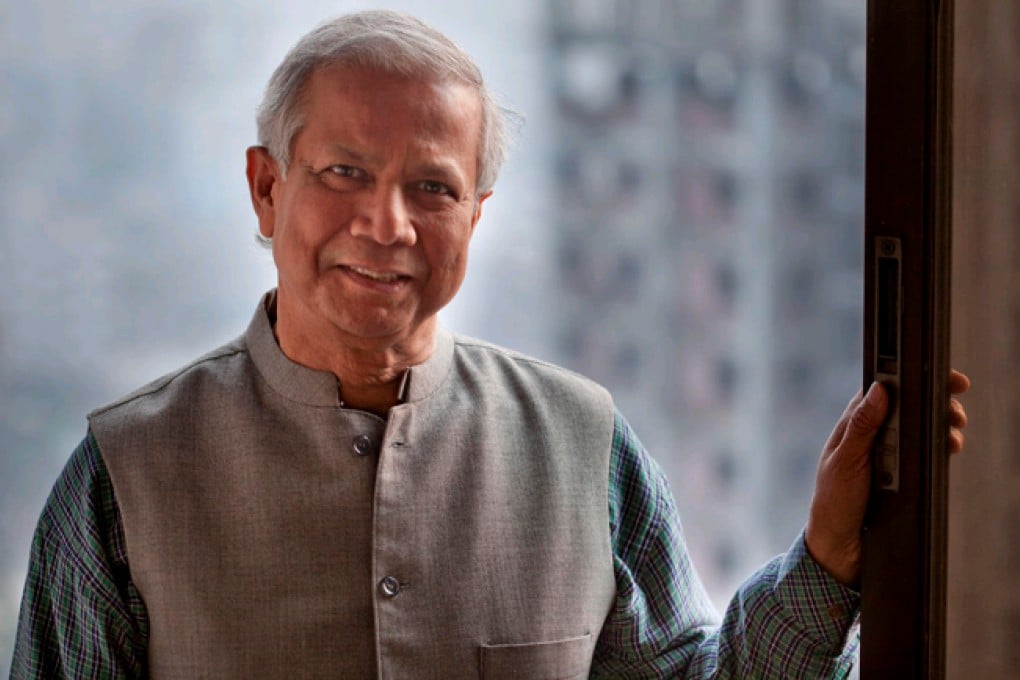

My life: Muhammad Yunus

The Nobel laureate and microfinance pioneer tells Charley Lanyon why the job of proving people are more than money-making robots has fallen to our children

I was born in a village in (what is now) Bangladesh (and was then British India) to a very low-income family. In 1947, when I was seven, we became a separate country, Pakistan. So the question became, what do we do with the country? How do we handle development? Two things became attractive to me: one was the law, because all our political leaders were lawyers, and the other was economics, because our issues were mostly economic. I chose to study economics at university. After I finished my master's degree in Bangladesh, I got a Fulbright scholarship. I got a PhD (from Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, in the United States) and started teaching at Middle Tennessee State University. In December 1971, I resigned and started teaching in Bangladesh. I saw famine and poverty, and wanted to see if there was a way I could help. I was doing little things for individual people. Then I saw loan sharks in the village and started lending money myself. That's how it happened. Microfinance was an accidental thing. Then I tried to connect borrowers to the local bank. I offered myself as a guarantor. The money involved was so small that it didn't bother me - I was just solving a local problem and it had nothing to do with theory. You see a ditch on the street and you try to fill it up - not because you have a theory about roads and transport, just because you saw a big ditch and wanted to make things easier for people.

As we grew bigger and bigger, the bank became more and more reluctant. So I thought, "Why don't I create a separate bank?" I got permission from the government, but it was hard for me because I was reluc-tant to operate under the existing bank-ing law. My position was that if we did this under the law, no matter how much we tried, it would become the same as any other bank because the law would push it in that direction. I wanted to make the borrowers the owners of the bank - under the existing law, that would have been complicated. But finally I got it done. In 1983, we created a separate law (and founded Grameen Bank). We borrowed from the central bank, loaned money to people and continued to expand. We wanted to make sure half the borrowers were women. It took us six years to reach that point. We saw that money going to the family through women brought more benefits than the same amount of money going through men. Gradually, (the percentage of women borrowers rose to) 97 per cent.

Winning the Nobel Peace Prize (in 2006) was a fantastic experience because all along I had been saying the same things - poverty is the denial of all human rights, entrepreneurship is something built into every single human being, the banking system is wrong and needs to be redesigned - and people showed little interest. But after the Nobel Prize, I would say the same things and people would think they were wise words. Doors that I couldn't open before were opened. People don't see that, along with Grameen Bank, I've created more than 60 companies and they are all dedicated to solving problems - not making money (Yunus was in Hong Kong over the summer as a keynote speaker for Nu Skin's 2012 Master Forum, where he discussed how individuals and corporations could create positive change). I realised that this was a new type of business. I call it social business: a non-dividend company to solve social problems.