Waste Water

Chaotic planning and over-development defaces the city's harborfront

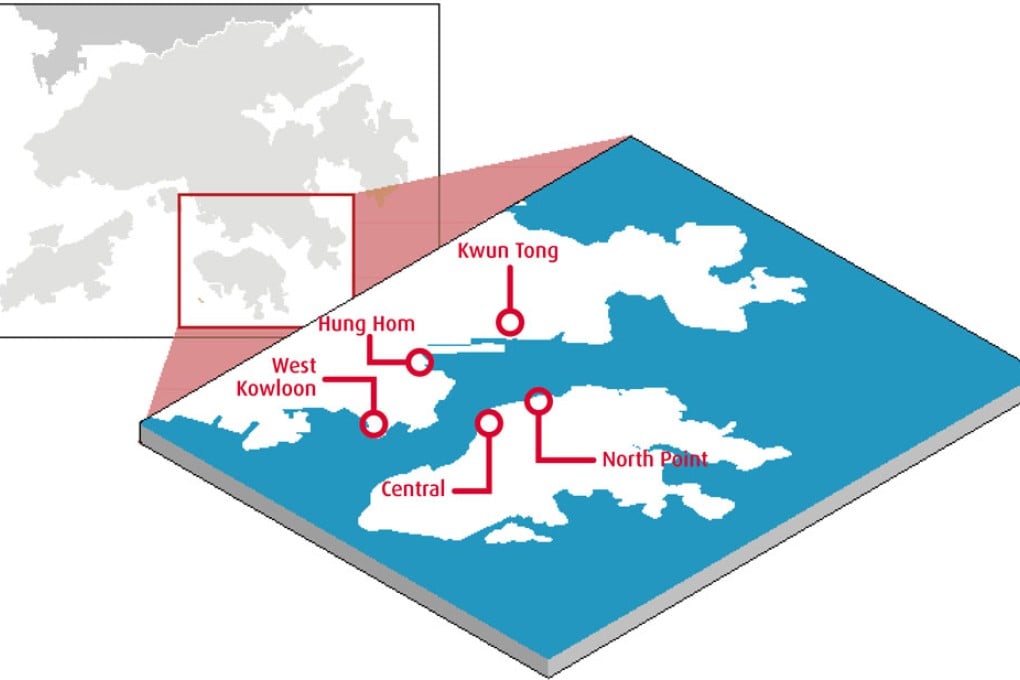

Hong Kong never knows what to do with the harbor. Despite being the most valuable asset and undoubtedly an icon of the city, Victoria Harbour has always been given a different treatment by the government at any given time—we used to try filling it up as much as we could, then we kind of stopped, then we started again for a road. We are now officially entering a new phase of our waterfront development with the recent opening of Lung Wo Road— formerly known as the P2 Road, the controversial road connected to the Central-Wan Chai Bypass—plus last month’s closure of the Harbour-front Enhancement Committee, the government’s advisory body on the harbor front development.

Without a proper harbor policy, or a master plan on waterfront development, what kind of waterfront are we really getting? For years, the government’s approach has been more about slogans and less about the unifications of plans. In last year’s policy address, Chief Executive Donald Tsang called for a need to “beautify the harbor front” and said he had delegated the Development Bureau to set up a Harbour Unit to “co-ordinate and plan harbor front enhancement initiatives.” One year later, we think it is now a good time to examine the ongoing waterfront development to find out how different the approaches are—some are promising while others are hindered by bureaucracy as usual—and determine if this is, at the end of the day, giving our city a better waterfront.

Central

By far the source of the most controversies, Central’s waterfront has gone through a decade of turmoil. The demolition of the 55-year-old Star Ferry pier in Central in 2007 triggered the city’s embrace of our heritage, and the government’s change in policies—as well as a change of principal officials—to better adapt with the public’s new urge to conserve. After that, Queen’s Pier, right next to the Star Ferry pier, was also removed—all of this was because of the construction of the Central-Wan Chai Bypass, a major transport link the government persuaded the public was necessary for the future development of Hong Kong. The bypass also required major reclamation in Central, which the government proved had “overriding public interest,” and would be the last reclamation in the harbor. The bypass will be in the form of a tunnel, whereas its linkage road, the newly opened Lung Wo Road, cuts across the waterfront and is six lanes wide.

What’s happening?

After much debate over the years, the Harbour-front Enhancement Committee has reached a consensus regarding the development density. They will lower the density to improve the views of the harbor from inland, with a large landscaped deck connecting the Central Business District to the new harbor front. Secretary for Development Carrie Lam announced last year that the government will not relocate Queen’s Pier to its original location after the bypass is completed. Currently there are still two proposals on hand for the waterfront and there has been no decision on which to adopt yet. In his latest policy address, Chief Executive Donald Tsang has included the development of the Central waterfront as part of his initiative to conserve Central, the city’s very first attempt to conserve not just single buildings, but an area.

North Point

The North Point waterfront is up for grabs—we are not kidding. But before we go into that, let’s have a quick geography lesson. Despite its location on the north of the island, North Point residents never really enjoyed the waterfront—the Island Eastern Corridor has blocked residents from going near the water, and only those living in waterfront developments, namely Cheung Kong’s Provident and City Gardens, can see the harbor. However these two developments are classic walled-building developments (a total of 31 blocks with 25 to 27 stories), blocking the airflow to the rest of North Point. Ms. Cheung, who has been running a newspaper stand for more than 20 years there, experiences the pollution firsthand and has developed allergy symptoms because of it. “We’re trapped between the walled buildings, but the breeze from the harbor front and the mountains can’t reach us,” she says. Eastern District Council chairwoman Christina Ting Yuk-chee adds, “Residents have been complaining to us for years but it’s not like we can tear down the buildings to start our urban planning all over again.”

What’s happening?

With the demolition of North Point Estate (near Java Road) seven years ago and the fact the former Government Supplies Department building in Oil Street has been empty since 1998, suddenly there are two pieces of premium waterfront land available in North Point. So far the government has not had any success in developing either of them. At Java Road, the former North Point Estate site is now a 37,000-square-foot plot of land. There have been plenty of hiccups. In 2002, the Housing Authority, which managed North Point Estate and the land under it after the estate was demolished, announced plans to give it back to the government, on the condition that the government would sell the land and allow for 3,430 residential flats to be built on the location (with a plot ratio of 10). Unsurprisingly, the plan for more walled buildings was widely criticized by local residents. In 2007, the Housing Authority scrapped the plan and returned the land to the government unconditionally.