Security concerns scupper Copenhagen’s celestial cycling lane

Danish capital’s lofty idea of a bike bridge in the sky falls through

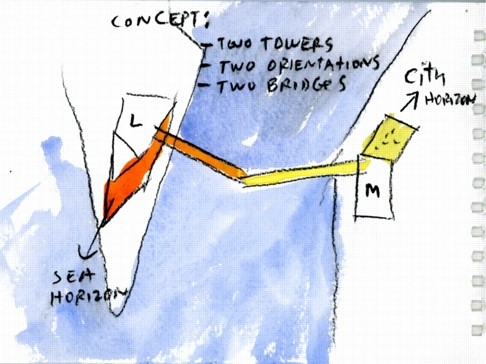

For a city as practical as Copenhagen when it comes to transport, the project seemed grand, almost frivolous: a glass-walled bike and pedestrian bridge suspended 30 storeys above the harbour, between two skyscrapers.

But after years of discussion, plus some premature reports that the scheme was about to go ahead, it seems plans for the so-called Copenhagen Gate were abandoned this week.

The idea dates back to 2008, when celebrated US architect Steven Holl’s company won a competition for the regeneration of the harbour in the Danish capital. It comprised a pair of skyscrapers on either side of a port inlet, containing office space and two hotels. A bridge between the towers was deemed necessary so the building on the outer side was no more than 500 metres from the nearest rail station, as dictated under planning laws for workplaces.

There was just one problem: twice a day, the large Copenhagen to Oslo ferry would sail between the two buildings. Holl’s solution was to place the cycle and pedestrian path 65 metres in the air, necessitating a long lift ride on either side.

While the kinked bridge, with its floor-to-ceiling glass sides and orange-and-yellow colour scheme, would have provided stunning views, cycling groups in Copenhagen were not convinced of its practicality.

“It would be fun, and a landmark, but it would never be something that would be used every day,” says Klaus Bondam, formerly Copenhagen’s mayor for roads and the environment and now the chief executive of Cyklistforbundet, the Danish Cyclists’ Federation. “You wouldn’t want to cycle, get in a lift with your bike, get on your bike and then get in another lift on the other side. It would be quicker to cycle round the harbour.”

In the end, the project fell foul of a more prosaic objection: security. The developers decided that allowing continuous public access to a 65-metre-high bridge would be so problematic they asked if they could make the route private.

Some sort of non-public link between the towers might still go ahead, but the plans for the development will now be redrawn after the city council rejected the scheme as it stands.

The developers, Harbour, now prefer the idea of a ground-level bridge that could open to let the Oslo ferry pass, a plan supported by Bondam. “The ferry only leaves once or twice a day, so it would be possible to have a lower-level bridge that opens,” he says. “You don’t necessarily need to go up 30 storeys. My suggestion would be to build a bridge at water level, and make sure it can go up whenever the ferry has to pass.”

Why was this not the first solution? More planning laws, Bondam says. When the scheme was first mooted in 2008, all cycle bridges had to be fixed. Since then, however, the rules have eased. This summer the Circle Bridge, made up of five circles of different sizes and jointed in the middle, opened in another part of the harbour.

Coming soon is yet another new harbour bridge, a futuristic retractable creation between the city centre and the new opera house designed by London practice Studio Bednarski.

Could such options not have been considered when the Copenhagen Gate was first proposed? Developers’ spokesman Nielsen told Politiken that, in retrospect, there had been some architectural hubris.

“Back then it was down to the architects to come up with a conceptual design, something which doesn’t always consider practicalities,” he said. “But subsequent analysis has shown it’s almost impossible to have a public pedestrian and cycle bridge at that sort of height.”

Guardian News & Media