Donnie Yen’s action choreographers on his and Jackie Chan’s lasting influence on movie making

- John Salvitti learned martial arts from Donnie Yen’s mother, and Yen himself, before working for the martial arts star as an action choreographer

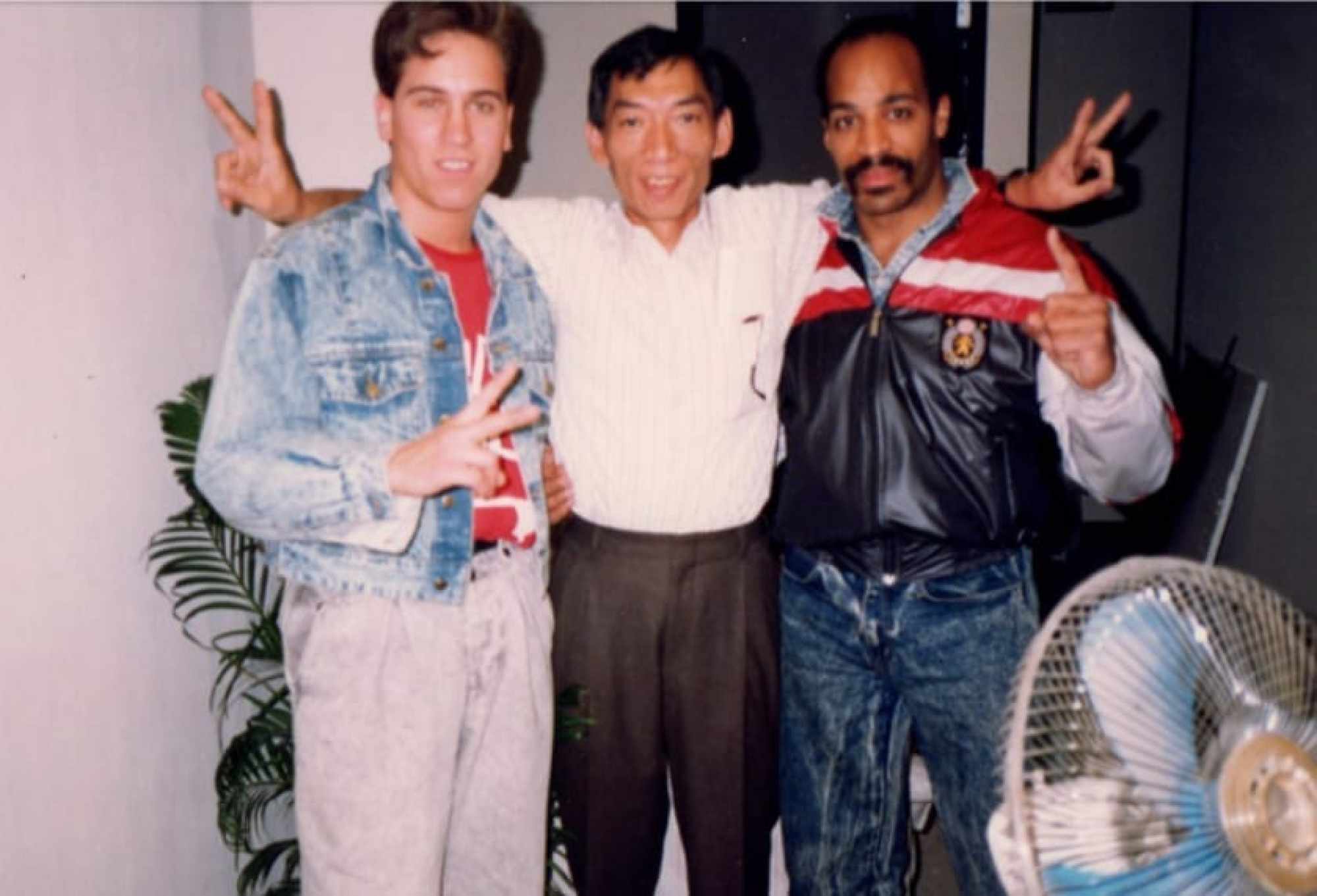

- Kenji Tanigaki, action choreographer for Henry Golding’s Snake Eyes film and Japanese series Rurouni Kenshin, has worked with Yen since the mid-1990s

The only Japanese member of the Hong Kong Stuntman Association, Kenji Tanigaki speaks Cantonese with a Japanese accent when he choreographs action scenes in Donnie Yen Ji-dan’s movies.

In an interview with the Post, Tanigaki recalls how he left an impression on Yen with his stunt work in Fist of Fury. “He had to fight many Japanese [in the series]. He asked me to help him out in 1996 when he started his own company [Bullet Films] to be a director.

“When directing Legend of the Wolf (1996), he started to put together his own stunt team. He didn’t have enough money [to pay the crew] then. The experience was very harsh. But I enjoyed it a lot.”

10 best Asian action movie stars working today

“Jackie Chan made me want to become a stuntman,” he says. “I imitated his drunken kung fu in Drunken Master [1978] when I was a child. I learned Hong Kong-style kung fu at Kurata’s school in Japan for four years. But Japanese action movies then were lame. The stunts were fake.

“When I arrived in Hong Kong, there were over 200 filmmaking companies listed in the [telephone directory] Yellow Pages. I turned up at the companies but they ignored me as I didn’t speak Cantonese.”

Tanigaki read the entertainment section of Chinese-language newspaper Oriental Daily and learned the local language from passers-by at McDonald’s every day. One day his luck changed when a talent scout approached him at McDonald’s and found him some work at the Tsim Sha Tsui police station.

“I had to dye my hair blond. In the police station, I sat on a bench with four people. We were asked to stand up and sit down many times. I was paid HK$300 for the work. It turned out it was for witness identification.

“The talent scout called me later for a bit part in a TV series. I got to know the action choreographers on set and joined the Hong Kong Stuntman Association in 1994.”

Unlike during the 1980s and ’90s when stunts were developed on set, Tanigaki says that from the noughties on, due to tight production schedules, action choreographers have got their own staff to enact the action scenes on set and made edited videos before shooting starts.

“Yen will watch the videos and ask for adjustments. He loves making changes. Although Yen is not the director, he calls the shots on set, requiring the cinematographer to use a certain lens for a scene, for example.”

Tanigaki won a joint Golden Horse Award for best action choreography in 2018, for the Chinese film Hidden Man. He’s a film director in his own right, having directed Yasuaki Kurata in Legend of Seven Monks (2006), and Yen in Enter the Fat Dragon (2020). Tanigaki credits Yen with teaching him all aspects of filmmaking.

John Salvitti is another long-term action choreographer for Yen. The martial arts expert from Revere, Massachusetts, says Yen is a visionary who passes on his filmmaking knowledge to all his team members.

“Donnie makes the style and technical calls. We pitch ideas. If he thinks they will work, we go along with them,” he tells the Post.

“Once shooting starts, he has pretty much mapped out what he wants to do. The team have to stay alert and ready.”

Salvitti was a student at Yen’s mother Bow-sim Mark’s martial arts school in Massachusetts in the 1980s. “Donnie graced the cover of [monthly magazine] Inside Kung Fu in 1982. I read this and was so intrigued that soon I [joined] his mother’s school. I eventually became Donnie’s student. I would watch his every move and study his way of training and explosiveness.”

Of all the Yen films he has worked in, Tanigaki says the shooting of Flash Point (2007) was the most memorable. “Shooting its ending takes three months, with many reshoots. We tried to create a new style of action choreography with MMA elements. So there was much trial and error. I brought 10 stuntmen from Japan to work on that film.”

Although the Hong Kong movie industry is in decline, with a drastic drop in output and wholesale migration of filmmaking talent to China, Tanigaki says local action movies have left a lasting legacy that will keep inspiring future generations of moviemakers around the world.

“Seventy per cent of foreign action choreographers grew up watching Hong Kong movies. The prolific Hollywood action choreographer Bradley Allan from Australia is a member of Jackie Chan stunt team.

Tanigaki went with Yen to Berlin to make the German TV series Der Puma – Kämpfer mit Herz, which was co-directed by Yen from 1999 to 2000. Their stay encouraged locals to become action choreographers, he says.

“The same happened [in 1993] when Jackie Chan stayed in Vancouver for six months to make Rumble in the Bronx (1995). I hope the Hong Kong movie industry will regain its former glory in future.”

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook