In Nijinsky, ballet's spark of genius smothered by madness

Vaslav Nijinsky was almost immobile at the last moment of his real life. Only his expressive hands moved, turning magazine pages as he waited outside the office of a pioneer psychiatrist at a Zurich asylum.

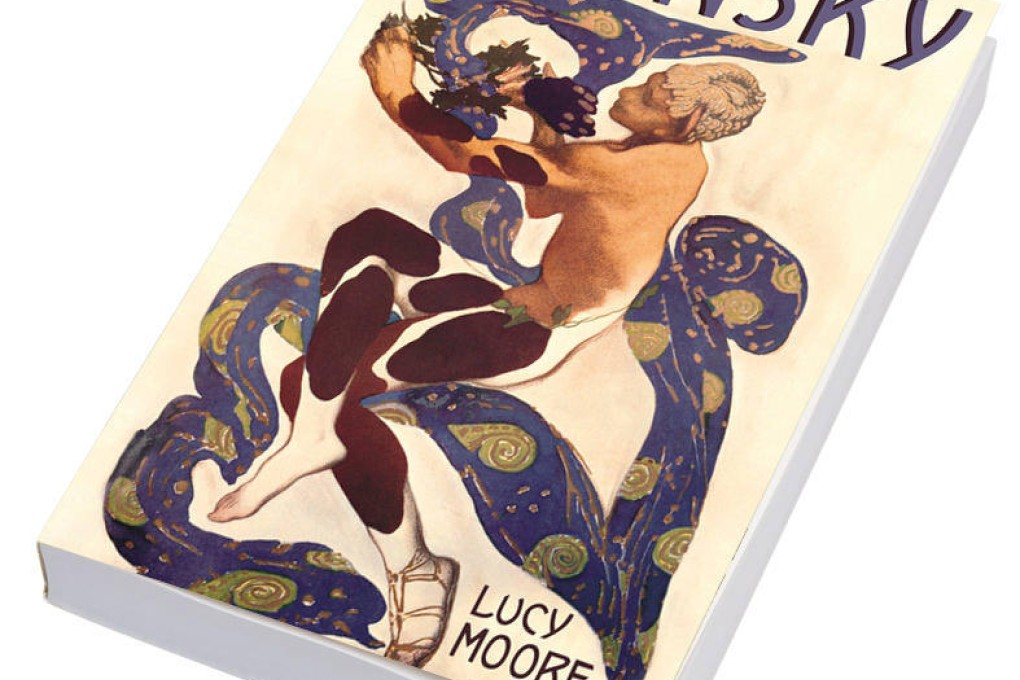

by Lucy Moore

Profile

Vaslav Nijinsky was almost immobile at the last moment of his real life. Only his expressive hands moved, turning magazine pages as he waited outside the office of a pioneer psychiatrist at a Zurich asylum. After a consultation the doctor privately told Nijinsky's wife, Romola de Pulszky, that her husband was incurably mad. Nijinsky already knew his condition; he had kept an inventory of his own disintegration in a journal. There followed 31 years of schizophrenia with rare lucid episodes. He was never himself again.

Just days away from Nijinsky's 30th birthday in 1919, and the biography is almost all over but for a coda on a fading legend.

The energy from his lowly childhood elevated him. As a student, he was cast by choreographer Mikhail Fokine, who wanted a male dancer with attitude to redress the sexual balance on stage - not a safe pair of hands to loft a prima ballerina, but a power. Nijinsky was certainly that.