Xinjiang exports rattled by coronavirus outbreaks in Central Asia as risks from US sanctions loom

- The share of exports in Xinjiang’s gross domestic product is declining, from 9.2 per cent in 2019 to 6.84 per cent in the first half of 2021

- Lacklustre export data has stoked worry about the impact of US sanctions, but virus outbreaks in Central Asia pose a bigger threat

This is the third in a series of stories looking at China’s Xinjiang province and how the far-western region is coping economically under a series of US sanctions over alleged human rights violations and the widespread use of forced labour.

“Previously, orders from them required more than a dozen trucks each month,” Zhang said. “Now they are all gone.”

First off, we need to recognise that Xinjiang’s economy isn’t really export driven; it’s much more dependent on investment

Its exports have been hit by dampened demand in neighbouring Central Asia, skyrocketing freight costs, and US sanctions over alleged human rights abuses of Uygurs and other Muslim minorities, charges which Beijing has repeatedly denied.

In 2020, Xinjiang’s total exports were valued at US$15.836 billion, down 12.2 per cent from 2019, a huge divergence from overall national growth of 1.9 per cent.

Though customs data shows trade has improved this year, with exports surging 50 per cent year on year in the first six months and 16 per cent compared with the same period in 2019, the share of exports in the region’s gross domestic product (GDP) is declining: from 9.2 per cent in 2019, to 7.96 per cent in 2020, and 6.84 per cent in the first half of 2021.

The lacklustre export data has set off alarm bells about the potential impact of international political controversy over alleged Uygur rights violations.

01:08

Xinjiang, China’s top cotton producer

Nevertheless, despite their high-profile nature, US sanctions have so far been all bark and little bite when it comes to Xinjiang’s economy – although they remain a major uncertainty, according to local traders and experts.

“First off, we need to recognise that Xinjiang’s economy isn’t really export driven; it’s much more dependent on investment,” said Nick Marro, lead analyst for global trade at The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

In the first half of 2021, China’s total exports contributed 18.51 per cent to national GDP, almost three times the proportion of Xinjiang.

“Trade flows [in Xinjiang] are relatively shallow compared to elsewhere in China, which might be reflected by the relative volatility in annual growth rates,” Marro said.

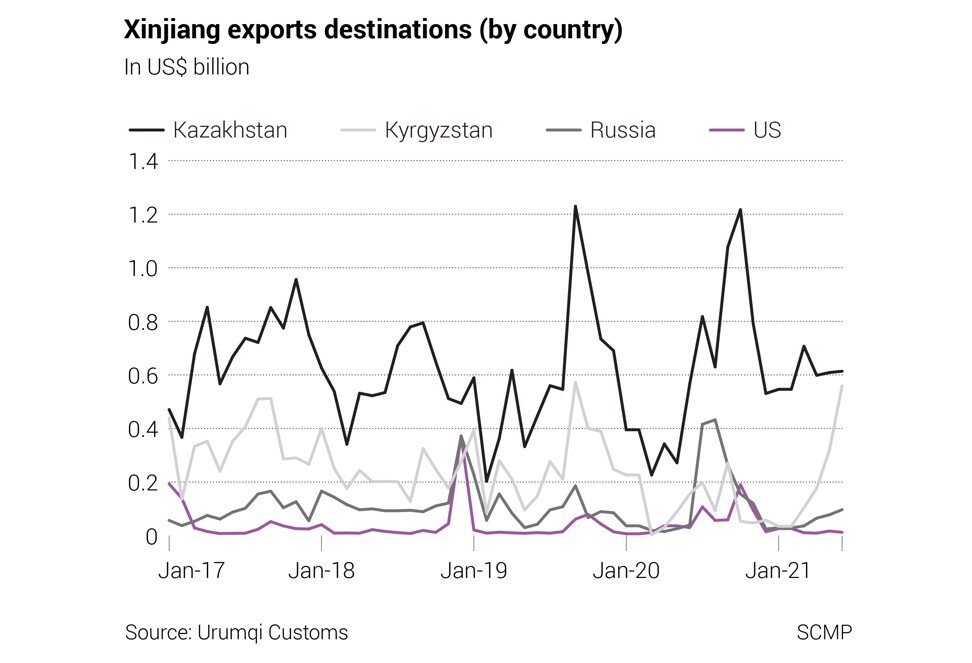

Exports to the United States have only accounted for about 2.6 per cent of Xinjiang’s total exports since 2017, according to calculations from the South China Morning Post based on customs data.

The region’s top export destinations remain Central Asian nations and Russia, so these countries’ economic conditions are the biggest factor affecting shipments abroad.

Exports to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan accounted for 75 per cent of the region’s exports in the first half this year, according to figures from Urumqi Customs in Xinjiang.

Products from Xinjiang accounted for about 45 per cent of total exports from China to Central Asia in the same period, data from China’s General Administration of Customs showed.

Rigorous border control at land ports and surging freight costs triggered by the pandemic have exacerbated the problem.

While the number of trucks crossing China’s borders has been more than halved due to virus control measures, freight costs have jumped tenfold since the pandemic began, said Zhang, from the logistics company.

“The road freight cost between Horgos to Almaty used to range from US$1,000 to US$2,000, but has increased to US$18,000,” he said.

Pandemic controls have also eliminated the small amount of cross-border retail trade that existed between China and its neighbours. Though small in scale, before Covid-19 residents could trade at designated markets straddling the border and sell to tourists.

“The pandemic has not only brought increasing freight, but also cargo delays, and traders may also need to pay additional fees for transport congestion,” said Jing Ran, an international trade professor at the University of International Business and Economics. “So exporters face more opportunity costs such as loss of sales, perishable goods and the risk buyers will drop orders.”

Xinjiang is also disadvantaged because most of its products are low-value added and labour-intensive, she said.

“As for low-value products, consumers have limited tolerance for price rises, so it’s difficult to offset the increasing costs by raising costs,” she said.

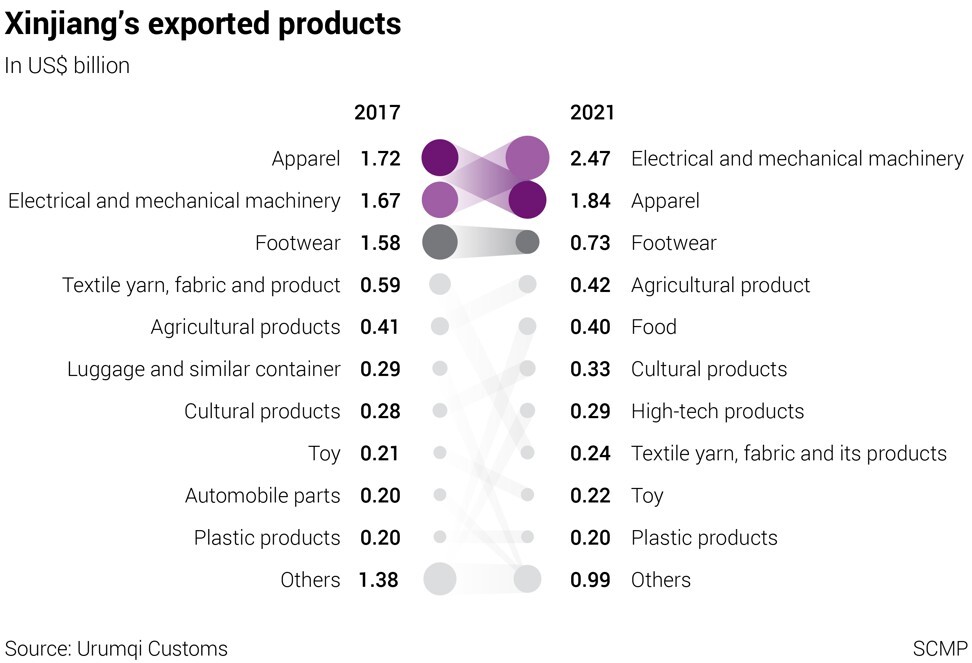

Since 2018, electrical and mechanical machinery products have accounted for most of Xinjiang’s exports, despite also being embroiled in allegations of forced labour. In the first half of this year, these products accounted for 30 per cent of total exports, while apparel took up about 20 per cent.

According to Urumqi Customs, major types of electrical and mechanical machinery exported to Central Asia include data processing machines and audio equipment.

The changing composition of exports reflects new investment in areas like electronics and hi-tech goods, which along with auto parts and chemicals, have seen greater production over the past few years, according to Marro.

“The quality of these goods may not rival production in other parts of China – the electronics industry clusters in Guangdong are much more sophisticated, for example – but lower land and labour costs have steadily attracted corporate investment away from China’s pricey coastal locations for much of the past decade,” Marro said.

While e-commerce and improved connectivity – including port infrastructure and the China-Europe Railway Express – have helped reduce trade costs and boosted reliability, Xinjiang’s export outlook is fundamentally shaped by economic development in Central Asia, analysts said.

“Central Asia is growing relatively fast, and the market will be able to absorb more Chinese goods in the future,” said Hans Holzhacker, chief economist at the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Institute, an intergovernmental organisation headquartered in Xinjiang.

“But it must diversify and find new sources of growth besides mineral fuels, otherwise Chinese exports to the region will suffer, no matter how good the transport infrastructure is.”

“The BRI has not yet been able to fully realise its potential in exports to Central Asia, as the growth of China’s exports to the region has been significantly less since 2013 than to the rest of the world,” Holzhacker said.

Concerns about emerging market debt and fragile post-pandemic growth in Central and South Asia will further complicate Xinjiang’s short-term export outlook, Marro said.

Facing uncertainty in Central Asia, Xinjiang has been building new trade ties, especially with Southeast Asian countries under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) since the beginning of the year.

In May, Xinjiang’s department of commerce arranged a forum with trade representatives from Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei, and two months later, another forum was held with representatives from Vietnam, the Philippines and Myanmar.

Trade figures for the first half of the year showed the effort was bearing fruit, with Xinjiang’s exports to RCEP countries growing 23.9 per cent year-on-year to 4.64 billion yuan (US$719 million). Exports to Vietnam increased 395.5 per cent, while exports to South Korea and Thailand jumped 176.7 per cent and 117.1 per cent, respectively.

Vietnam bought 91 wind turbines – valued at US$172 million – from Xinjiang in the first seven months this year, which accounted for more than 60 per cent of the country’s total imports from the region.

China’s largest wind turbine maker, Xinjiang-based Goldwind Science & Technology, announced in June it had installed its first overseas offshore wind turbine in the waters of Vietnam.

Still, Marro said diversification of exports to RCEP countries is more rhetoric than reality in the long run.

“There isn’t much Xinjiang can do,” he said. “Geographically, for instance, it’s less competitive than coastal provinces like Guangdong and Fujian, which can benefit more from tighter supply chain integration under RCEP with Southeast Asia.”

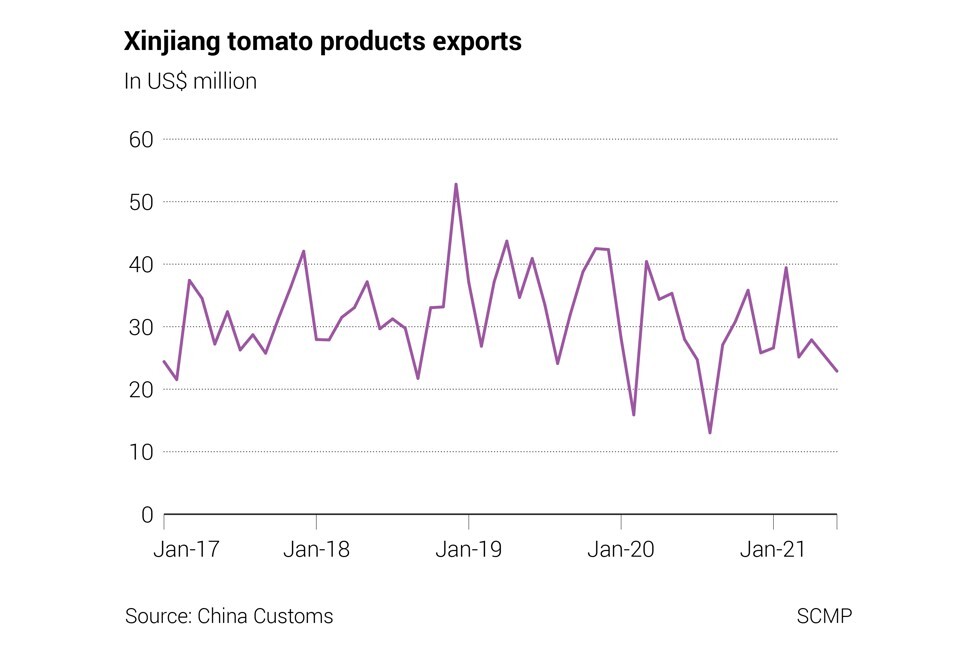

US sanctions have so far not caused substantial damage to Xinjiang’s foreign trade, including tomato exports, or the local textile industry. But they remain the biggest risk for the future, especially if machinery and electronics manufacturing is targeted, analysts said.

“In terms of supply chains and sanctions, the story is more complicated for third parties,” Marro said.

“Xinjiang is a major global supplier of cotton and solar panel materials, and it might be painful for midstream and downstream buyers to comply with the US bans – particularly those working with contractors in countries, such as in Southeast Asia, where product procurement might be more opaque.”