For semiconductor self-sufficiency, China must collaborate, not just innovate

- The Western semiconductor landscape is an intertwined global network, fostered by decades of collaborative research and intellectual property sharing

- Beijing must learn to marshal its domestic and international resources in a similar way to realise its ambitions

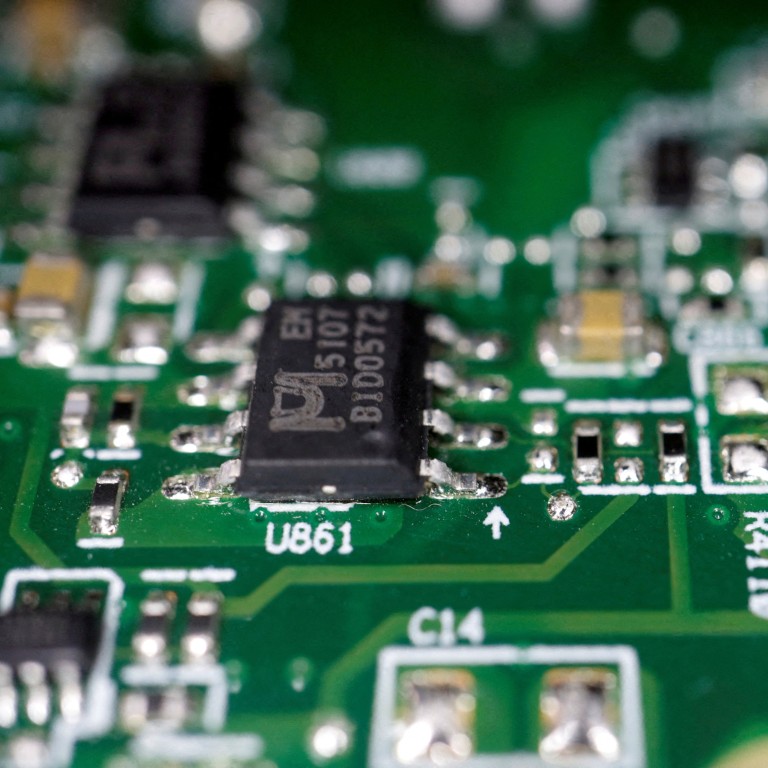

China is the top semiconductor market, with sales of about US$180 billion in 2022 representing more than 30 per cent of the global total. It leads the world in both exports and imports of semiconductors. Mainland China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan account for more than 80 per cent of global semiconductor fabrication. However, although manufacturing is centred in East Asia, critical chip design software and manufacturing equipment remain controlled by the West.

The nature of the challenge faced by China is epitomised by ASML, a Dutch company that makes the photolithography systems needed to manufacture semiconductors. About 4,000 companies contribute components, materials, expertise and patents that converge at ASML, whose machines embody technologies from nations including the US and Germany.

The Western semiconductor landscape represents a complex and intertwined global network, fostered by decades of collaborative research, development and intellectual property sharing.

The comprehensive nature of this network extends from foundational research to precision engineering, such that academics and specialised manufacturers form a robust moat around the West’s dominance in the industry. This is how the US is able to leverage restrictions on electronic design automation (EDA) software and capital equipment to lock out China.

Nations outside this network face significant hurdles, as success in the semiconductor industry is determined not only by financial investment or technological prowess but also by active participation in such global networks.

The West’s advantage lies not just in individual components – top-tier universities, advanced corporate labs, and a network of suppliers and manufacturers – but in the strength and synergy that arises from their collaboration.

For example, leading foundries work in close partnership with the top EDA providers. The trust-based partnerships that underpin this ecosystem present a formidable challenge to Chinese newcomers.

The implications of such a technological leap are vast, promising to propel computing into a new era of heightened processing speeds coupled with diminished power demands. Should China surmount the scalability and integration challenges within chip fabrication, the rewards promise to be transformative.

Many semiconductor titans have emerged from the US’ liberal market economy. But now, the risk-reward profile of the semiconductor industry is often seen as unattractive by most venture capital investors, with the landscape dominated by Chinese VCs.

Tech given greater importance than defence in Beijing budget

In this intricate nexus of cooperation and competition, China’s drive towards semiconductor self-reliance is a strategic imperative with global repercussions. It is a delicate balancing act that requires China to skilfully leverage domestic innovation while engaging in international collaboration.

Just as the US has marshalled its global resources to contain China’s semiconductor ambitions, China must also effectively coordinate all domestic and international resources to realise its strategic aspirations.

The semiconductor industry’s future will depend on the ability of all players to navigate a win-win balance where competition spurs innovation and collaboration fosters growth. The successful performance of the semiconductor global ecosystem hinges on the concerted harmony of its interconnected players.

Winston Mok, a private investor, was previously a private equity investor