Advertisement

Opinion | Why China fearmongering is bad for America

- China bashing, which has intensified ahead of the US presidential election, is shortsighted, undermines justified criticism of China and, critically, distracts from America’s real challenges

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

12

As the US presidential election gears up, the anti-China rhetoric has ratcheted up. Just last week, the Biden administration announced an investigation into Chinese-assembled smart cars, which it said could collect sensitive information about Americans and US infrastructure. This came after Donald Trump promised to impose tariffs of 60 per cent or more on Chinese goods if re-elected.

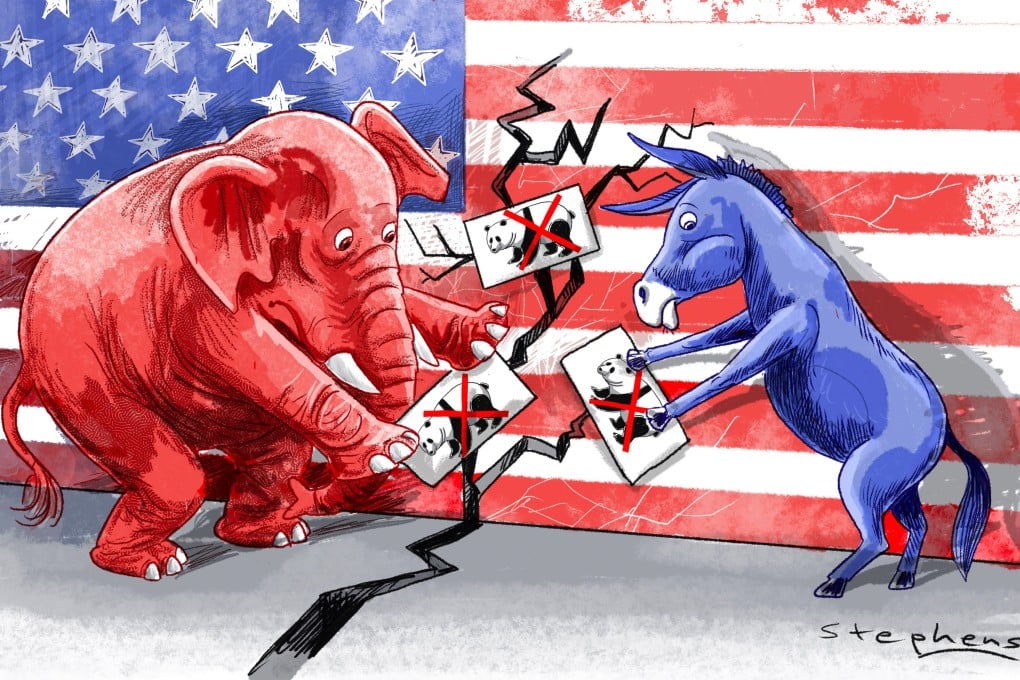

The political incentive for anti-China fearmongering is obvious, as the Republican and Democratic parties seek to rally support and show a tougher stance on China.

What may boost short-term political aims, however, comes at the expense of grappling with America’s real challenges, not least its fraught relationship with Beijing. While criticism of China is often warranted, reckless and unsubstantiated fault-finding confuses voters and distracts from America’s inability to maintain global dominance – all while doing nothing to resolve Sino-US tensions.

When it comes to China bashing, the race to the bottom continues. Last December, Republican senator Rick Scott set his sights on Chinese garlic or what he calls “sewage garlic”. In a letter to Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, Scott wanted an investigation into Chinese garlic imports and their food safety, warning of an “existential emergency that poses grave threats to our national security, public health and economic prosperity”.

No, Scott was not kidding. Nor was Raimondo when she said she was “upset” over Huawei Technologies unveiling a smartphone with an advanced Chinese chip during her visit to Beijing last year.

More gravely, US military leaders have joined the fray of China alarmism. Last year, it emerged that the four-star air force general Mike Minihan had gone as far as to warn internally of war between China and the US. “I hope I am wrong,” Minihan said. “My gut tells me we will fight in 2025.”

Advertisement