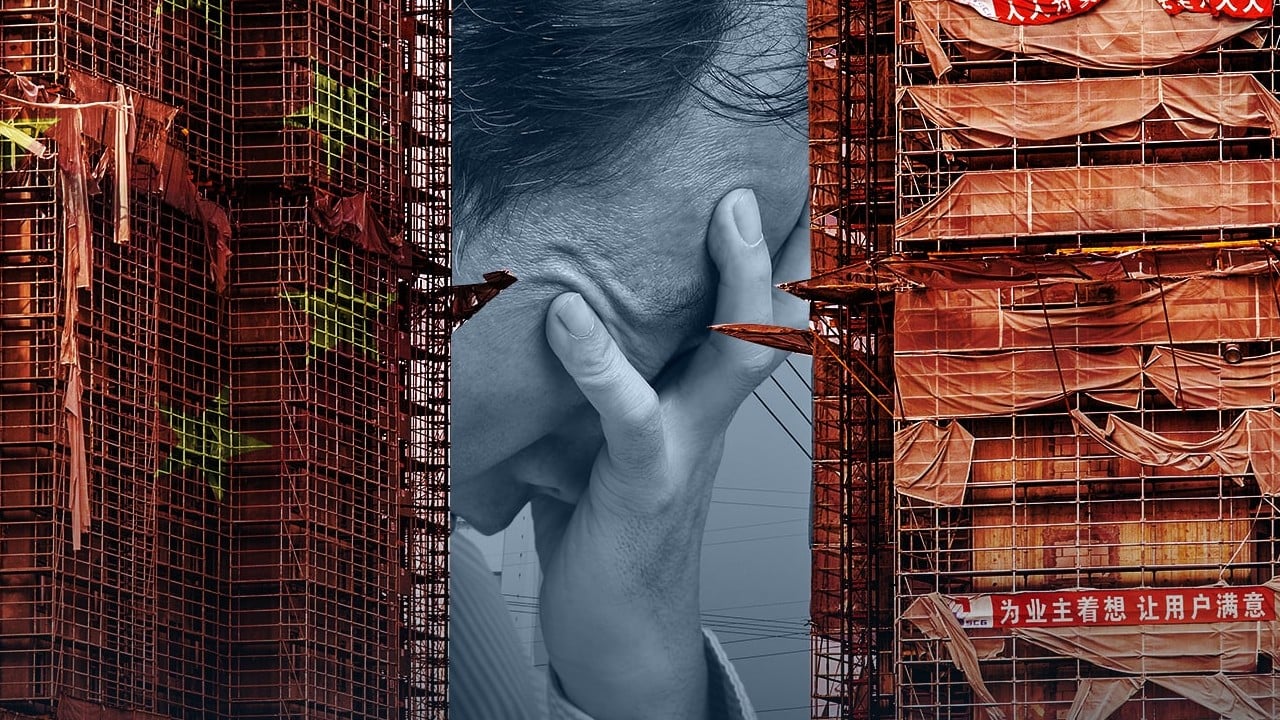

Unlike Japan, China’s property crisis won’t lead to lost decades

- China’s crisis stems from overenthusiastic investment while Japan’s was a result of speculation and bank profligacy

- To revitalise its economy and calm international jitters, Beijing should look to other industries with higher investment yields, such as the tech sector

But China presents a different story, one that is worth examining in greater detail.

Since around 2017, China has moved to curb its frothy property market, regulating prices to prevent excessive fund inflows even as the supervision of banks tightened. In line with this policy direction, average home prices have generally trended lower, particularly since August 2021.

But the construction boom also created a massive property sector, estimated to now account for as much as 23 per cent of China’s GDP. This boom has since peaked and offers diminishing returns, especially in small and medium-sized cities. The result: China has the capital stock of a developed economy – its housing space per person, for instance, is 430 square feet, as much as in Germany or Japan – but not the income.

During the property price decline, Japan attempted to lift the economy from its severe downturn by channelling vast funds towards infrastructure investment and cutting interest rates. The consumer tax was raised to 5 per cent in 1997 from 3 per cent and pension insurance premiums also increased.

With both new and international accounting rules demanding the disclosure of more accurate non-performing loan figures in Japan, a Goldman Sachs report in 2001 estimated that Japan’s non-performing loans had reached 237 trillion yen (US$1.9 trillion). This was nearly 38 per cent of all bank loans at the time, and about five times the official figure published by banks.

In reality, the total value of non-performing loans in the 15 years after Japan’s property bubble burst was only 110 trillion yen, less than half the estimate.

In 1998, as the property crisis evolved into a debt and banking crisis, Japan took the unprecedented step of nationalising banks in trouble.

Shigeoki Togo, then CEO of Nippon Credit Bank, which was nationalised and later renamed Aozora Bank, continues to criticise the takeover, insisting he was confident of the bank’s recovery and that it was the change in accounting rules that forced his bank into bankruptcy.

Japan’s example suggests that one way to proceed is to find other industries with higher investment yields to achieve an intensive, short-term economic revitalisation.

What China can learn from Japan to deliver needed economic reform

Fortunately, China has globally competitive tech-driven industries, such as in batteries and electric vehicles and will be able to boost exports even amid a semiconductor battle with the US. Also, China’s well-balanced savings and investment rates, each at over 40 per cent of GDP, are far better than in many other countries.

Property woes could lower this investment ratio to 35 per cent, a gap of roughly US$1 trillion given China’s GDP of US$18 trillion. But as long as China makes up the difference through its current account surplus, its economy will stay in equilibrium.

And that may be enough to calm international jitters over the Chinese economy. China does not have to change its accounting rules over non-performing loans.

Yoshihiro Sakai is adviser to the Office of the President at the University of Tokyo. He is a former market operation officer at the Bank of Japan and a senior economist