China’s workforce paradox and how to solve it

- China’s employment conundrum, where younger people are perceived as past their prime at age 35 and older workers retire too soon, must be addressed

- Workers across age groups should embrace lifelong learning and juggling multiple roles. AI can be deployed, with care, to avoid widening inequalities

China is wrestling with a severe demographic challenge. The National Health Commission expects that by 2025, over 20 per cent of citizens will be over 60, the biggest aged population globally. This, paired with a birth rate that hit a record low of 6.77 per thousand people in 2022, portends a stark 1:1 worker-to-retiree ratio by 2050 compared to 2.26:1 today.

But thanks to smarter lifestyle choices, better nutrition and wider access to a steadily improving healthcare system, workers in this cohort are living longer, healthier lives than the generations before them.

Regardless of their motivation, they find themselves at the mercy of a system that views them as outdated, even redundant. They are forced to leave the workforce despite their willingness and capacity to contribute.

This workforce paradox, where the young feel they have prematurely peaked and the old feel unjustly sidelined, will become one of the biggest misallocations of societal resources if unresolved. There must be solutions.

First, workers across all age groups must embrace lifelong learning. In a world where technology and artificial intelligence are taking centre stage, adaptability is essential. Continuous education and skill development are not merely choices but necessities. For younger workers, they ensure relevance and competitiveness. For the older generation, they offer a pathway to pivot careers or re-enter the workforce.

The emergence of a “slasher” culture where people juggle a variety of roles is another outlet for workers young and old seeking better work-life balance and more meaningful careers. It’s a trend worth watching: a survey conducted by Beijing Youth Daily estimates that there are around 80 million slashers in China.

Joining the ranks of the slashers can help younger workers diversify their income sources and stave off burnout. Older workers who take on multiple roles can capitalise on their deep work experience by branching out as independent experts and coaches.

Finding real solutions to joblessness among China’s youth

Employers have an important role to play here as well, by acknowledging the potential of their workers across all age groups and committing to retraining. McKinsey Global Institute’s findings indicate that up to 220 million Chinese workers – or 30 per cent of the workforce – may need to transition between occupations by 2030.

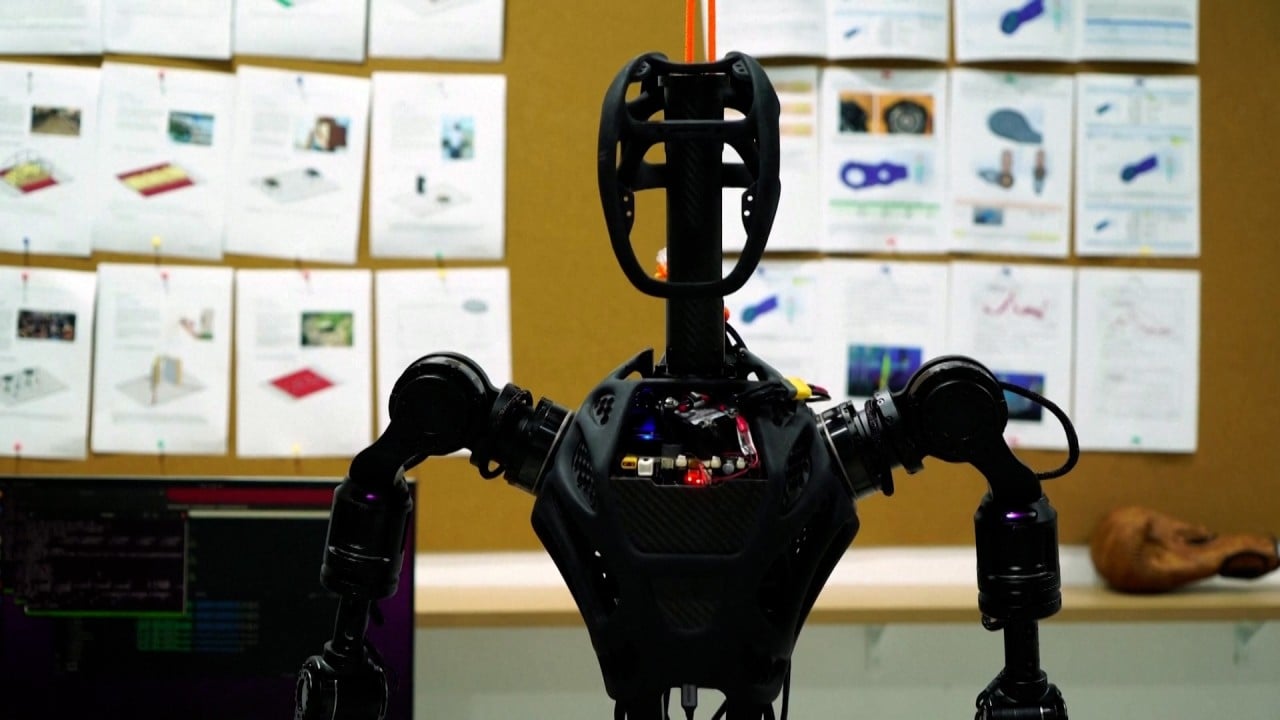

More importantly, while AI and automation pose a threat to the current workforce, necessitating upskilling, they may also hold the key to overcoming China’s demographic challenge. According to McKinsey, AI has the potential to add $2 trillion to China’s economy, primarily by enhancing worker productivity.

Nevertheless, we must remain cognisant of the potential economic upheaval and social disparities these technologies may engender. Used properly, they have the capacity to level the playing field and uplift productivity. But the risk of technology and AI widening the gap between the haves and have-nots and creating even more social disparity is real. China’s demographic conundrum, magnified by its vast population and regional inequalities, is daunting.

We should be optimistic. By leveraging technology, China has made remarkable strides in its economic development, elevating hundreds of millions from poverty. There is no reason technology should not again be the solution to China’s looming demographic challenge.

Joe Ngai is the chairman of McKinsey & Company’s Greater China region