For Hong Kong’s healthcare reforms to work, better policies are needed for its ageing population

- Latest reforms reflect an ageing policy still too narrowly focused on disease prevention rather than ageing successfully

- Affordability of chronic disease management must be tackled as well as health literacy and the wider socio-economic factors that support good health outcomes

Patients are also encouraged to have a regular family doctor as their first contact point for healthcare and the management of chronic conditions. A Hong Kong study found that patients with multiple ailments who had a regular source of primary care were 23 per cent less likely to be hospitalised than those who did not.

But, for all the efforts to improve primary care in Hong Kong, structural barriers have not been considered sufficiently. Affordability of chronic disease management has long been an issue. Older people are among the most frequent users of the public system – three-quarters of elderly Hongkongers have at least one chronic condition, which usually requires multiple follow-ups, long-term medication and investigations.

Moreover, on two points, the blueprint – or more broadly, the ageing policy in Hong Kong – is narrowly focused. First, good healthcare alone does not guarantee good health. According to the World Health Organization, 30-55 per cent of the differences in health outcomes within and across countries are down to a collective of wider social factors.

In short, the conditions in which people are born, grow up, work, live and age all shape the conditions of daily lives, which in turn affect their health. Health differentials arise from the societal distribution of these factors – the more socially disadvantaged often lack access to (or knowledge of) the necessary resources conducive to health, for example.

Take health literacy. Provision of healthcare services is a two-way street – even in the presence of a world-class and affordable system, what it offers has to be made known and comprehensible to those who need it. Health literacy is poorer among those who are older, have poorer education standards and live in inadequate housing.

The notorious complexity of the booking and referral system of the public sector in Hong Kong often intimidates those who warrant necessary medical attention, resulting in delayed treatment (or, at the opposite end, pursuing unnecessary consultations for minor ailments).

The traditional idea of health equating to healthcare has hindered how resources are allocated and how the impact of policies is measured. Social and economic policies may not focus on health, but they will inadvertently affect the outcome.

It’s a ‘sick care’ system: experts say we must rethink healthcare for elderly

None of these health determinants fall into the realm of healthcare. Policymakers should take into account the health dimension when formulating, say, housing, welfare, environmental and transport policies.

Second, the blueprint has largely associated ageing with chronic diseases. Even in the absence of chronic disease, ageing results in declining physical and cognitive functions, which may lead to dependency and increased use of health services.

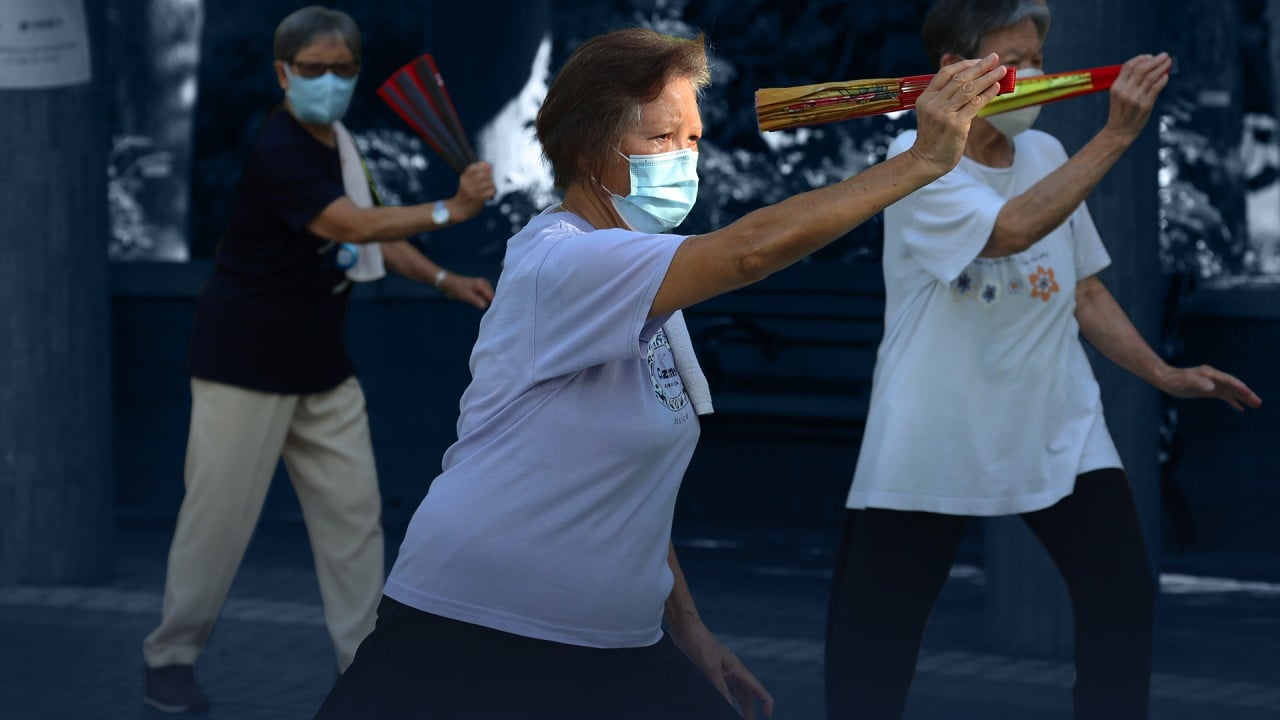

Population ageing is a global phenomenon; Hong Kong is no exception. What Hong Kong urgently needs is a road map away from a fear of ageing to a future that thrives on ageing. It is imperative to realise that ageing successfully means more than a mere absence of disease. When longer lives in good health are combined with physical and social infrastructure that enable older people to be productively engaged, all of society benefits.

Eric T.C. Lai is the Research Assistant Professor at the Institute of Health Equity at the Chinese University of Hong Kong

.jpg?itok=x0VyVnpg&v=1655360011)