US extends rivalry with China to the moon as it resists cooperation and seeks control over mining

- Nasa claims its Artemis lunar programme will promote diversity and cooperation, but fellow space powers China and Russia have been left out in the cold

- With the US attempting to lay down rules for mineral extraction, the new space race looks set to divide the world – and the moon – along Cold War fault lines

There’s enough strife on land, sea and in the air to keep US Cold Warriors and their Wolf Warrior counterparts in China sparring for a long time to come, but the race to create zones of influence and secure resources doesn’t begin and end with planet Earth.

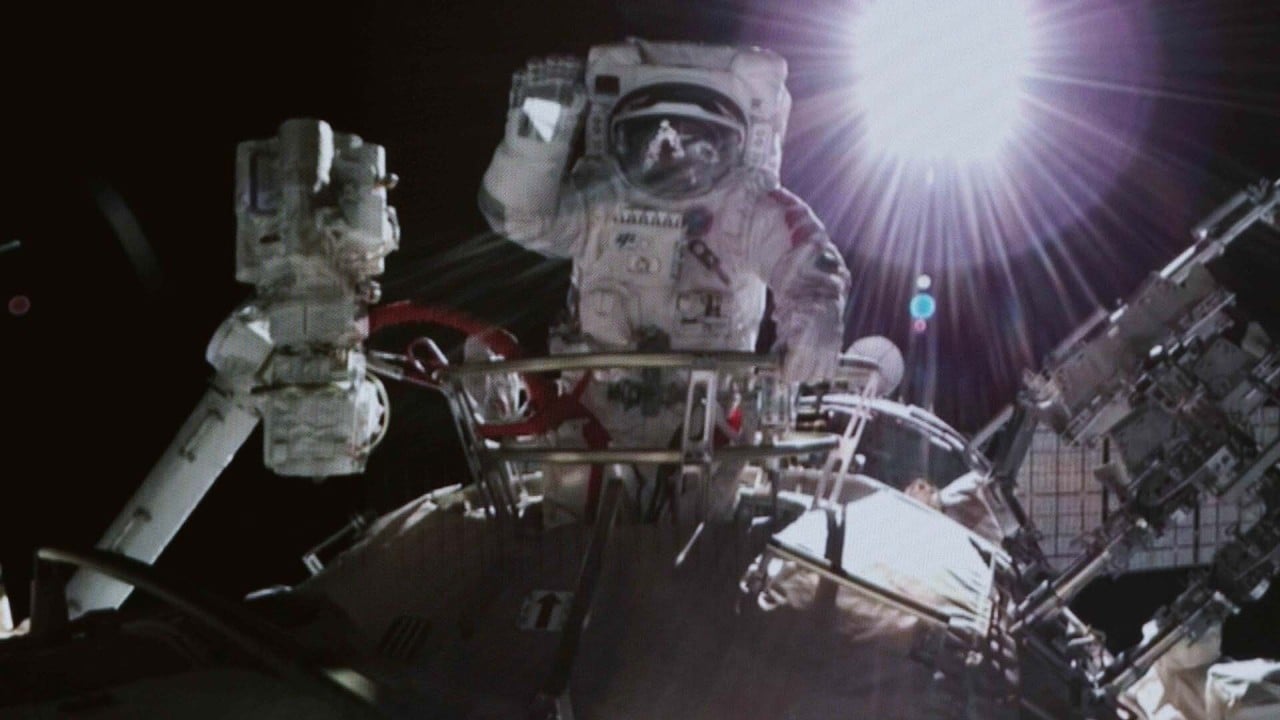

“Through Artemis, Nasa aims to land the first woman and first person of colour on the moon,” the mission statement reads. The US will “collaborate with commercial and international partners and establish the first long-term presence on the moon”.

At first glance, both China and Russia would be logical international partners, but the statement has a distinctly American accent.

It’s not the first time the US has tried to set the terms by which other nations can explore Earth’s only natural satellite. A US-scripted “Moon Treaty” was drawn up in 1979 but eventually withered away because the tiny handful of nations capable of competing with the US in space were not interested in signing away their rights.

Even the flag-waving president Donald Trump came to disdain the treaty because it suggested that the moon should be treated as part of a “global commons” rather than as a private resource base that individual nations and corporations could exploit.

The executive order issued by Trump is still in effect and the language has been altered only slightly. The goal of sending the “first woman and next man” to the moon was amended by the Biden administration to read “first woman and first person of colour”.

There are several ironies inherent in the way US leaders talk about the space programme. One is the partisan political flavour; the Democrats emphasise its links with identity politics, while Republicans emphasise the capitalist free market element.

But neither party wants to be stuck with the budget shortfalls and delays that have dogged the programme from day one. And no one is talking about including China.

If human diversity was really a serious goal of the Artemis programme, there would be scant reason not to cooperate with China. Or Russia for that matter. But why should China and Russia sign on to a day-late, dollar-short programme jump-started by Trump that defines the rules of exploitation on US terms?

What the mission statement is really saying is that the US reserves the right to exploit the mineral resources of the moon, and will do so with allies of its choosing and within guidelines of its own creation. As for China and Russia, the only two serious rivals to the US in space, they have been left out in the cold.

The Artemis Accords add another brick to the regulatory firewall the US has built regarding cooperation with China in space. The 2011 Wolf Amendment prohibited such cooperation, with the unsurprising result that China has taken a go-it-alone approach ever since.

The implicit anti-China gist of the Artemis programme is symptomatic of US party-driven politics in general. On the one hand, there’s a seemingly unbridgeable political divide at home; on the other, one administration looks the same as the other when viewed from afar.

The ostensible aim of the Artemis programme is to promote cooperation, diversity and set down rules for lunar exploration. In reality, it is dividing the world into two camps, following the familiar East-West fault lines established in the last Cold War.

Philip J. Cunningham has been a regular visitor to China since 1983, working variously as a tour guide, TV producer, freelance writer, independent scholar and teacher