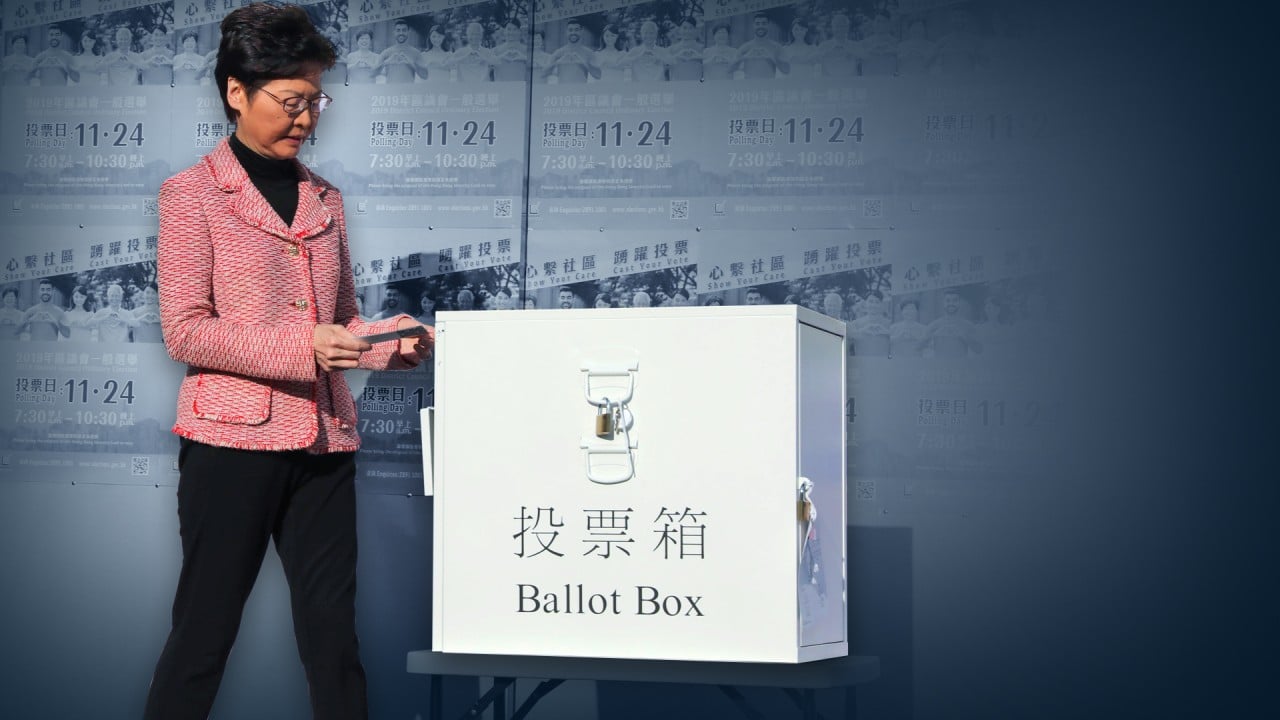

As Hong Kong prepares for Legco polls, a lesson from the lead-in-water scandal

- While efforts to ensure competition in the election are welcome, a truly improved system would give lawmakers the political room to do the sort of work that exposed excessive levels of lead in water at a public estate in 2015

But securing nominations is no walk in the park: former lawmaker Ronny Tong Ka-wah, now leader of Path of Democracy and a government adviser, has said securing nominations has been unexpectedly difficult.

Worse, what if the aspiring candidate doesn’t get past the eligibility review committee? That would make nominators supporters of people who were deemed unfit to run – a blotch on their patriotic profile.

Those who wish to be part of the election – whether by running or nominating someone to run – have to navigate treacherous political terrain.

Surely there must be more than a handful of acceptable and capable patriots to fill these seats? Otherwise, it will be ridiculous.

It is good that there is growing awareness of the need to pay attention to public perception. If the Legco election is to be billed as a showcase of the new and improved political system, it must be competitive. It’s important to acknowledge that healthy competition boosts performance.

We ought to recognise that, besides the drama inside Legco and the rioting, once upon a time, the opposition – and the competition to win public support – did do some public good.

Uncovering the high levels of lead in building water pipes was one example. Still, opposition lawmakers failed to secure enough votes to invoke Legco’s special powers to investigate because the government had enough allies.

Image matters, but so does substance. A truly new and improved system would allow lawmakers to have the political room to do this sort of investigative work, and serve the public well.

This begins with allowing those who nominate and vote for candidates to the legislature to do so without making them read the tea leaves while being strapped into political straitjackets.

Alice Wu is a political consultant and a former associate director of the Asia Pacific Media Network at UCLA