Opinion | To woo Asean, Russia needs to offer trade, not just arms

- Over the past decade, Moscow has consciously pursued its own pivot to Southeast Asia, hoping to exploit booming markets and the space opened up by intense US-China rivalry in the region

- Moscow’s recent vaccine diplomacy will help, and in the longer run it needs to build an economic relationship based on more than arms sales

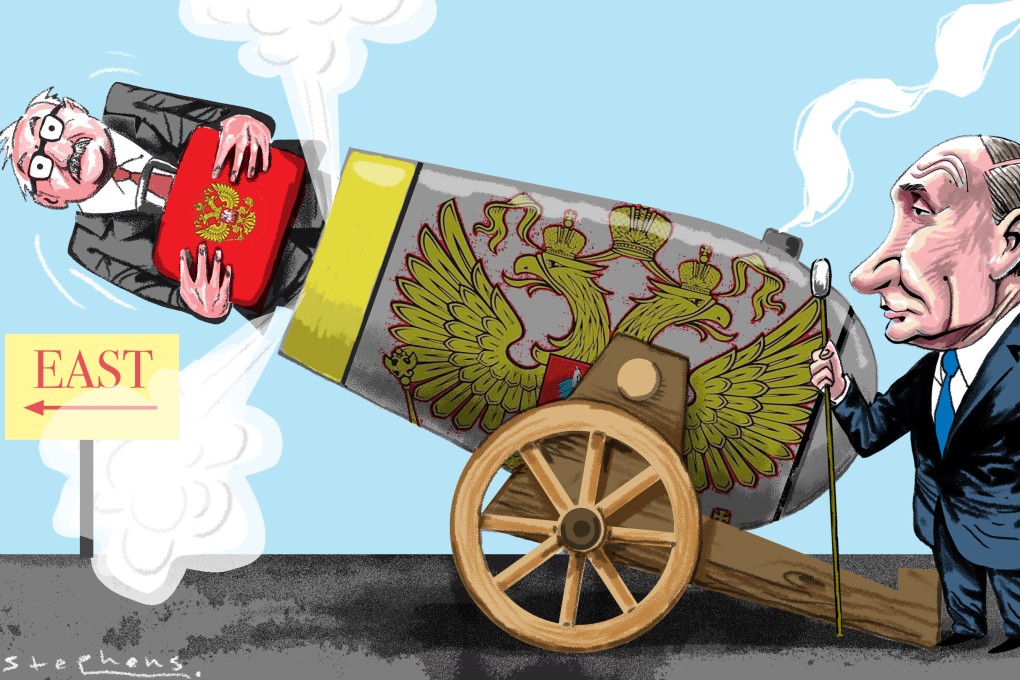

Summing up the cold-blooded maxim of 19th-century Europe, a French officer declared, “There is no judge more equitable than cannons. They go directly to the goal...” Here in the 21st century, a resurgent Russia is following the same logic, using its state-of-the-art “cannon” and military technology to win over vital regions such as Southeast Asia.

In an era of Sino-US rivalry, the heirs of the Soviet empire are consciously presenting themselves as a benign yet resourceful alternative to the two superpowers. The special summit this month between Russian and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ chief diplomats signals a shared interest in deepening bilateral strategic relations.

But Russia’s quest to regain its historic place of pride in Southeast Asia, once a major theatre of its Cold War rivalry with the West and Beijing, has been far from smooth.

Stretching across 11 time zones, from Vladivostok to Saint Petersburg, Russia is a transcontinental behemoth with direct borders with and vital interests in both the western and eastern extremes of the Eurasian land mass.

Beginning with Peter the Great’s southern and eastern push into Asian heartlands, an ostensibly “European” Russia increasingly became a major player in Asian geopolitics.