In the past couple of decades, nothing has been as prominent in remaking the global economy and reshaping global geopolitics as China’s rise and globalisation. China’s accession into the World Trade Organisation in 2001 – the

landmark inception of the world’s most populous nation into the global capitalist system – drove both China’s explosive growth and economic globalisation.

In the past year, however, a completely different theme has come to the foreground:

decoupling. Many in Washington fear or suggest that China and the United States, the world’s two largest economies, might go their separate ways, due to fundamental divergences in their philosophy on economics, governance and politics.

The idea, reportedly put forward by China hawks in the Trump administration, including trade adviser

Peter Navarro,

gathered steam this year as negotiators repeatedly failed to reach a comprehensive solution despite marathon US-China

trade talks.

In theory, decoupling would mean demolishing the supply chains, freezing cooperation initiatives and tearing down the geopolitical bridges that were built to facilitate such exchanges.

Indeed, decoupling has already started. US multinationals have begun to relocate some manufacturing operations out of China or sought alternative suppliers as trade tensions rise. US Congress is working on a

host of regulations to restrict bilateral economic and technology exchanges. In retaliation, Beijing has redoubled its efforts in areas of high-end manufacturing traditionally dependent on US imports, such as

semiconductors.

Decoupling has also affected both nations’ trading partners, with their declining orders hitting

export-oriented economies such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

In past decades, multinationals from the developed West made China their go-to manufacturing hub by relocating their assembly lines there, under the doctrine of

comparative advantage.

As a result, major US brands, from Apple to HP, IBM and Nike have become almost completely dependent on China for their supply chain. American multinationals such as Boeing, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and McDonald’s have also made huge profits in what was the world’s last untapped market.

In other words, China’s rapid evolution from economic backwater to the world’s second largest economy, largest exporter, chief foreign direct investment destination, and

largest foreign reserve holder was made possible by free trade and economic globalisation, and thanks to the help of developed economies from the US, Europe, and Japan, to the Asian tigers of Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea. The developed world, and the overall global economy, have also benefited from China’s economic rise.

The US desire to decouple from China comes out of its long-standing complaints about the communist state’s unfair trade practices and market-unfriendly policies, grievances shared by most of China’s trade partners in the developed West.

Washington is also concerned about China’s growing threat to regional and global security as

Beijing’s moves in recent years signal more authoritarianism at home and more assertiveness overseas.

Washington is obviously prepared to isolate the communist state globally, as evidenced by a

‘poison pill’ clause in the recent US-Mexico-Canada trade agreement aimed at forcing America’s trading partners to choose between the US and China.

US multinationals can neither afford the wholesale relocation of their plants out of China nor replace Chinese suppliers easily. An exodus of foreign firms from the world’s manufacturing hub would not only deal a deadly blow to economic globalisation but might also signal the beginning of the end of China’s growth story.

That is perhaps why the US and China chose to reach a

phase-one agreement on Friday. It looks like Washington has yet to find a place to sustain its protectionism, and Beijing may have to retract its earlier rhetoric about the revival of Maoist self-reliance.

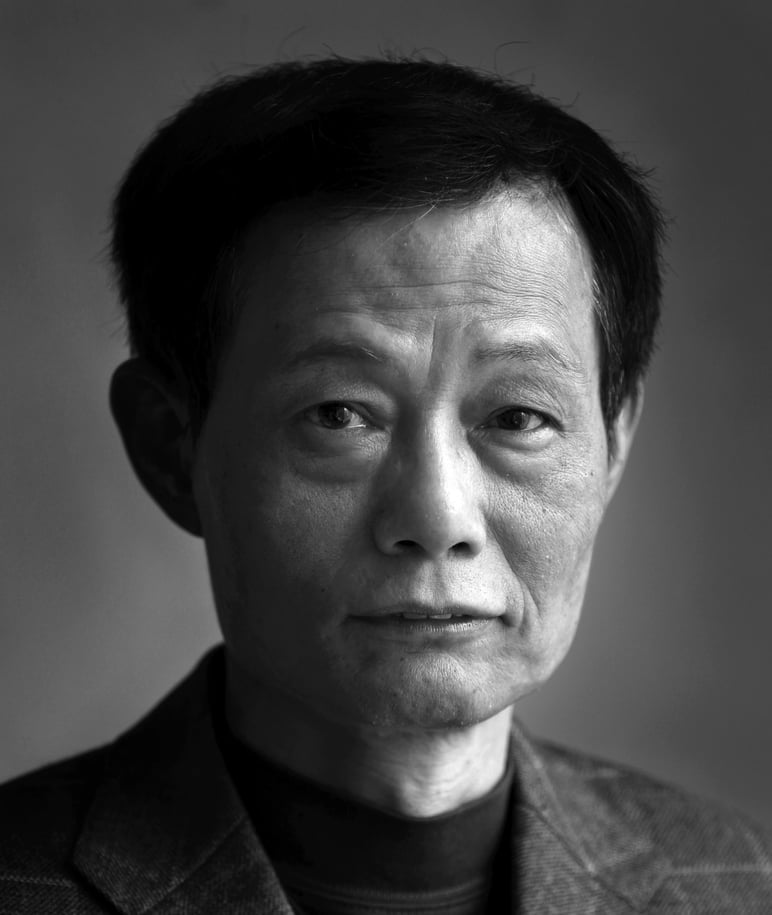

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on this topic since early 1990s