From peaceful protests to violence to terrorism: Northern Ireland’s ‘Troubles’ could show where Hong Kong is heading

- The conflict in Northern Ireland in the 1970s and ’80s, which led to a campaign of terrorism by a radicalised minority, offer a warning amid Hong Kong’s protests, due to their similar beginnings and escalation

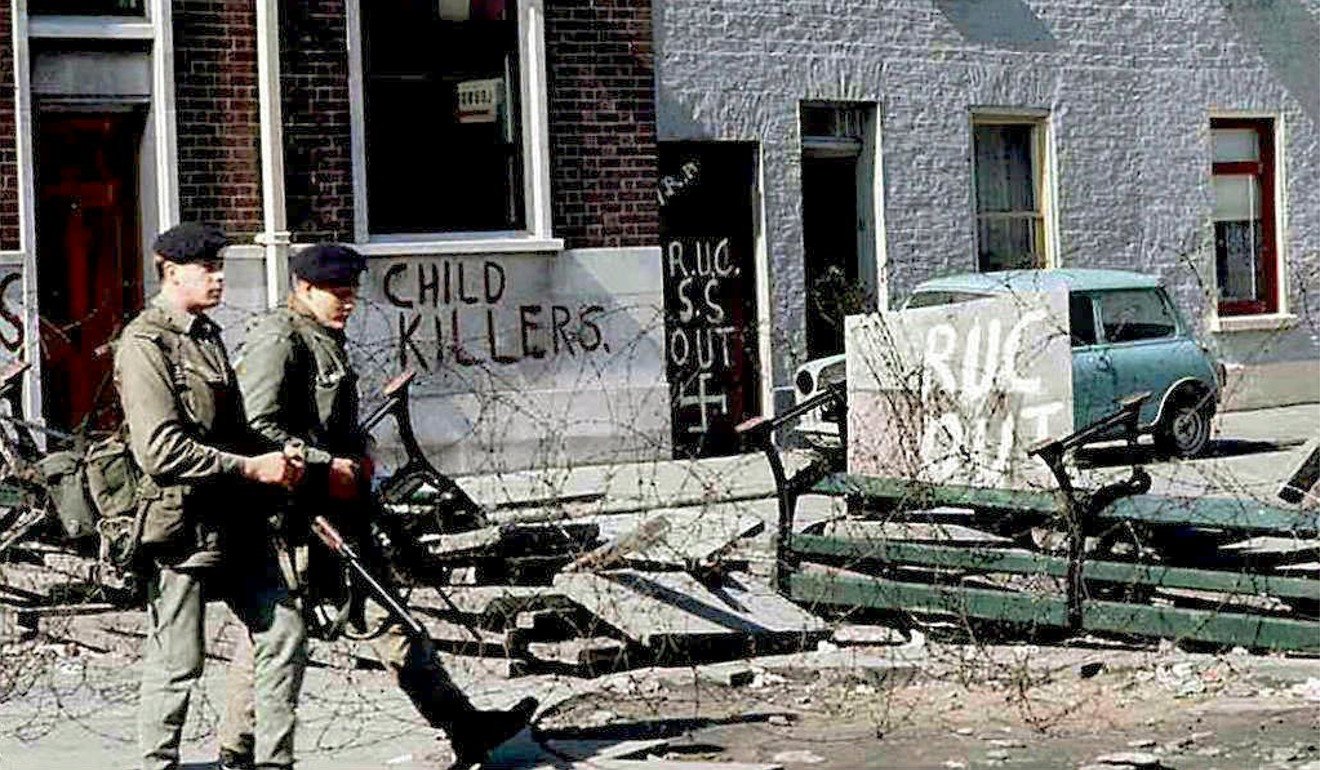

The crowds surged through the streets, demanding basic political rights. They were met by club-wielding riot police firing tear gas and rubber bullets. The clashes became routine, reflecting the gap between an aroused populace and an isolated and unresponsive government.

This sounds very much like Hong Kong, where I live, in the summer of 2019, but in fact describes Northern Ireland 50 years ago. As the crisis in Hong Kong shows no sign of resolution, the strife increasingly resembles the early years of what became known as “the Troubles” – a conflict that lasted 30 years and left 3,000 people dead.

I covered Northern Ireland as a journalist in the 1970s and 1980s. Over the last three years, I have studied that history in detail while researching and writing a book about the life of the late Professor Kevin Boyle, a leader of the Northern Ireland civil rights movement and later a prominent human rights lawyer.

The Troubles began as a peaceful protest movement demanding that the province’s minority Catholic population be given the same political and civil rights enjoyed by the Protestant majority and other British citizens. The initial response of the North’s Protestant-dominated government, however, was indifference, hostility and support for police efforts to stifle the movement.

In Northern Ireland, the government’s unwillingness to address demands for basic civil rights also sparked clashes, with the police using rubber bullets and tear gas in largely futile efforts at crowd control. As a journalist in Belfast wrote in 1971, tear gas had “enormous power to weld a crowd together in common sympathy and common hatred for the men who gassed them”.

Hong Kong police and protesters need to make peace, to end the insanity

By the time the Northern Ireland authorities grudgingly conceded some of the basic civil rights demands in the early 1970s – an end to gerrymandered electoral districts, equal opportunity in housing and jobs – it was too late. Growing numbers of Catholics came to see the Northern Ireland state itself as illegitimate. Demands for specific reforms gave way to calls to overthrow the system altogether.

For the Irish Republican Army, or IRA, this meant the start of a campaign of violence aimed at severing the North’s British connection and creating a united Ireland.

In Northern Ireland, the failure of peaceful protest and police heavy-handedness sparked the IRA’s campaign. Hong Kong has thankfully not yet reached this point. Still, for me, events in Hong Kong, with roads closed, transport disrupted, tear gas in the air, bring back memories of the challenges of navigating daily life in Belfast in the 1970s.

In 1969, Boyle played a prominent role in a civil rights march attacked by Protestant extremists. A lifelong opponent of violence, he responded with increased efforts to find a political way forward. Others, including participants in that same march, moved towards violence and terrorism. It is not unreasonable to worry that the uncompromising approach of the Beijing and Hong Kong governments risks pushing some of the youthful protesters in a similar direction.

Mike Chinoy was a long-time foreign correspondent, serving as CNN’s first Beijing bureau chief and as senior Asia correspondent. He is currently a Hong Kong-based non-resident senior fellow at the University of Southern California’s US-China Institute. Reprinted with permission from YaleGlobal Online. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu