Opinion | How a people’s jury system is helping Chinese courts to open up as part of vital judicial reforms

- Grenville Cross says the recent case of a man who languished in prison for a murder he did not commit is but another miscarriage of justice in China. However, two recent reforms to Chinese law should help prevent such cases

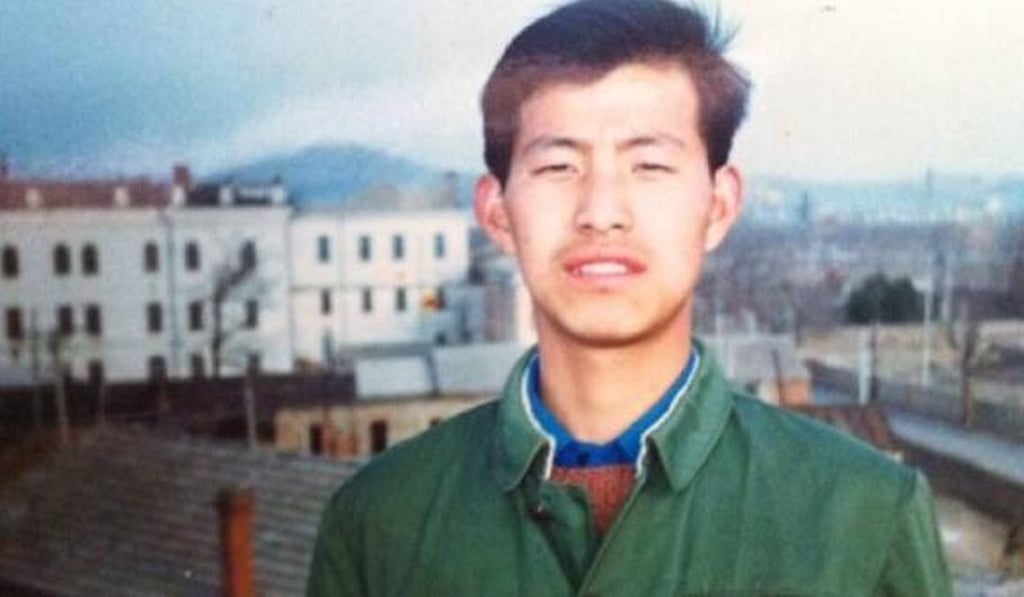

However, Jin’s conviction has been reviewed by higher tribunals, resulting in several retrials. In October, the latest retrial concluded in the Jilin High People’s Court, with prosecutors agreeing with defence lawyers that the facts were unclear and the evidence insufficient. Although the formal verdict is still awaited, Jin’s lawyer, Xi Xiangdong, said “the court recognised that Jin had not committed a crime and was therefore not a suspect”.

Jin’s case is but another miscarriage of justice arising from coerced testimony. However, recent reforms to China’s criminal procedural law should help curb such abuse. The court’s focus is now on whether the alleged confession was made voluntarily, not its truth. If the prosecution cannot show the suspect made the confession freely, the judge is now required to exclude it, as in Hong Kong.

In April, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee enacted a law on people’s assessors, which enables citizens to try cases with professional judges. In consequence, people’s assessors will “have equal rights” as judges in trials, unless the law specifically provides otherwise. Although the assessors cannot vote on legal questions, they can discuss them, and they vote with the judges on issues of fact, which are decided by the “principle of majority rule”.