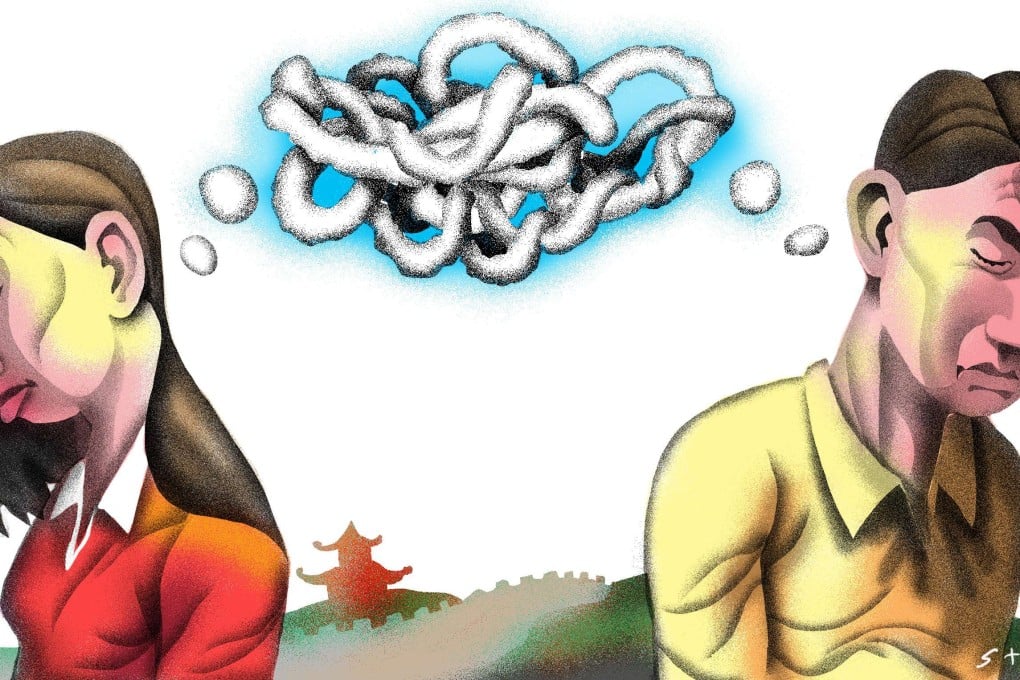

China in the 21st century: Confucianist outside, confused inside

Kerry Brown and Sheng Keyi explore what Chinese people believe as their lives grow more materially rich and their country pursues its dream of national rejuvenation

For all the outward confidence of the officials, the reality is that China is now in a period of vast confusion. There is no clear moral path that Chinese follow, nor an easy faith they subscribe to, no matter how powerful and materially wealthy their country becomes. Indeed, morals and faith seem to have vanished. In modern times, the government has tried to erect new sources of belief, with Confucianism taking the lead position. These days, all over the country, you can see key words from the lexicon of Confucius plastered on the walls of houses – “proper behaviour”, “rights”, “wisdom”, “fidelity”. Even planes and airports have Confucian slogans daubed over them.

What would Mao have made of Xi Jinping’s China?

Blame communist China’s moral bankruptcy for its lack of charity

But this only ends up seeming deeply ironic. While the vast majority of Chinese people are still scrimping and saving, plenty of those higher up who have become wealthy in the era of material enrichment since 1978 have multiple houses, bank accounts, businesses and lovers. Blithely talking about Confucian social order in this sort of context just comes across as empty words.

Confucianism gives great-looking outer clothing. But its real appeal to people’s hearts disappeared long ago

For the government, at least, Confucianism gives great-looking outer clothing. But its real appeal to people’s hearts disappeared long ago. Most people in China have become very good at telling apart what is said and what the real meaning is underneath. They are masters of piercing through formalism to the deeper reality. The main thing now is that, while people can say what they like, they still have to guard against stepping over the many red lines strewn around the place. And those legal lines in China, the lines of the permissible, are very vague. They are becoming ever easier to step across.

This sense of ever present danger means there is no modern Lu Xun, the great writer from the Republican era, to illuminate life with shafts of delicate irony. Intellectuals are largely silent. Lively young people on the internet use humour to handle the outside world. They describe a topsy-turvy world where reference to one thing points to another. Only, there are no easy rules of translation so at least they evade capture. In this context, where saying one thing almost invariably means you are talking about another, working out what Chinese in the 21st century believe in has become even harder. What do they have faith about?

Chinese themselves don’t have time to think about this sort of question. They feel they are always trying to catch up with everyone else. They are too busy working out what’s true and false in the crazy world around them. They focus on the immediate world around – their homes, families, networks. Some have faith, for sure. In a few rich villages, there are churches so large they have been destroyed by the local government, with believers being persecuted. Elites in the more developed areas have started to believe in an all-powerful God, but they can’t speak their faith out openly; they just have to keep it quiet to themselves in their souls. The most you can conclude when you look at Chinese society now is that the young don’t exactly believe anything, and they are not concerned about questions of spirit or soul. For them, it’s a matter of just finding out how to do things and getting by.