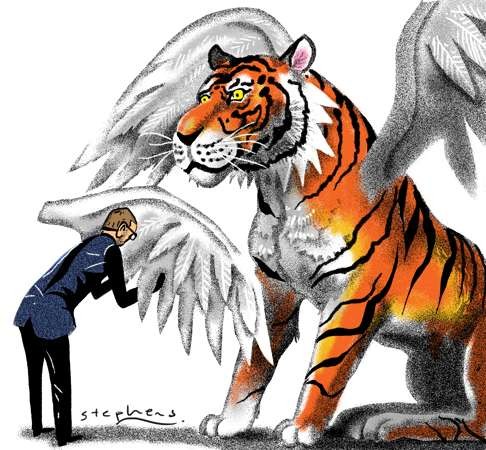

By making too many concessions to China, the West has given ‘wings to a tiger’

Robert Boxwell says Western investment has helped strengthen a China that seems less interested in human rights than ever

Since Tiananmen Square, Western business interests have hijacked politics

The same could be said for practically every negotiation the West has had with Beijing since; non-stop, predictable concessions, usually in return for promises that don’t arrive. Since Tiananmen Square, Western business interests, drooling over China’s billion people, have hijacked politics, ignoring inconveniences like human rights with a greed-driven insouciance. A few months after taking office in 1993, Bill Clinton pledged to tie the annual renewal of China’s most-favoured-nation trading designation to improvements in human rights. “The core of this policy will be a resolute insistence upon significant progress on human rights in China,” he said to an audience that included student leaders from China alongside business leaders from the US. “Whether I extend MFN next year, however, will depend upon whether China makes significant progress in improving its human rights record.”

China’s road or the Western way: whose economic development model will prevail?

Clinton’s “resolute insistence” didn’t last a year. The students left and the business leaders stayed. Human rights became just one of “the full range of US interests in China”, demoted by the money to be made trading with the Tiananmen crowd and their friends. They called it “engagement”. At least back then China’s leaders played along, making vague promises about trying to improve human rights. Today they tell the West to shut up and mind its own business. Two decades of a cheap yuan and millions of migrant workers ballooned both China’s trade surplus and billionaire count. Meanwhile, migrant workers jump off the roofs of factory dormitories. It’s socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Watching Mark Zuckerberg humiliate himself sucking up to Beijing is watching a rich guy give away something money can’t buy

Thanks to Western investment and markets, China now has the world’s second-largest economy and largest military, yet doesn’t seem to quite like the rules that got it there. The West helped transform a China that is massively stronger than a generation ago and appears to be less interested in human rights than ever. Watching Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg humiliate himself sucking up to Beijing is watching a rich guy give away something money can’t buy. It’s entertaining, but it’s also a reminder that fools with money and short-term views continue to drive the West’s politics. If you run a tech business in Silicon Valley, you can have a state dinner with Barack Obama and Xi Jinping (習近平). If you run a bookstore in Hong Kong, you can have a state dinner with the guards.

Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg meets China’s propaganda chief in Beijing

During Brzezinski’s meeting with Deng, foreign minister Huang Hua (黃華) summed up the situation by invoking an old Chinese proverb: “Appeasement of Moscow,” he said, was “like giving wings to a tiger to strengthen it”. Through decades of doing just that with China, Western leaders have given plenty of wings to the tigers in Beijing.

Perhaps no promise was more hopefully accepted than that of “one country, two systems”. When Margaret Thatcher, meeting Deng for the first time, indicated Britain would like to stick around in Hong Kong, the old man set the tone for negotiations by threatening to invade. “I could walk in and take the whole lot this afternoon,” he told her bluntly. “There is nothing I could do to stop you,” she replied, “but the eyes of the world would now know what China is like.”

Fog of uncertainty descends on Hong Kong in wake of bookseller ‘mess’

If Deng had invaded Hong Kong, or simply turned off its water, he would have made China a pariah in the West, weakened his hand with the Soviets and aborted China’s gestating era of economic transformation. Yet Britain blinked rather than call his bluff, like the rest of the West since.