Do electric cars have the range to go the distance in China’s rural towns and villages as they battle for buyers’ hearts and wallets?

- The average budget among car buyers in rural China mostly clustered around 50,000 yuan, according to a May survey by China EV 100

- With that budget, they require a driving range of between 100 kilometres and up to 300 kilometres

This is the first of a three-part series on the push for electrification in the world’s largest vehicle market, looking at the challenges of selling so-called new energy vehicles in rural China where manufacturers must balance between performance and price in a market of limited charging infrastructure.

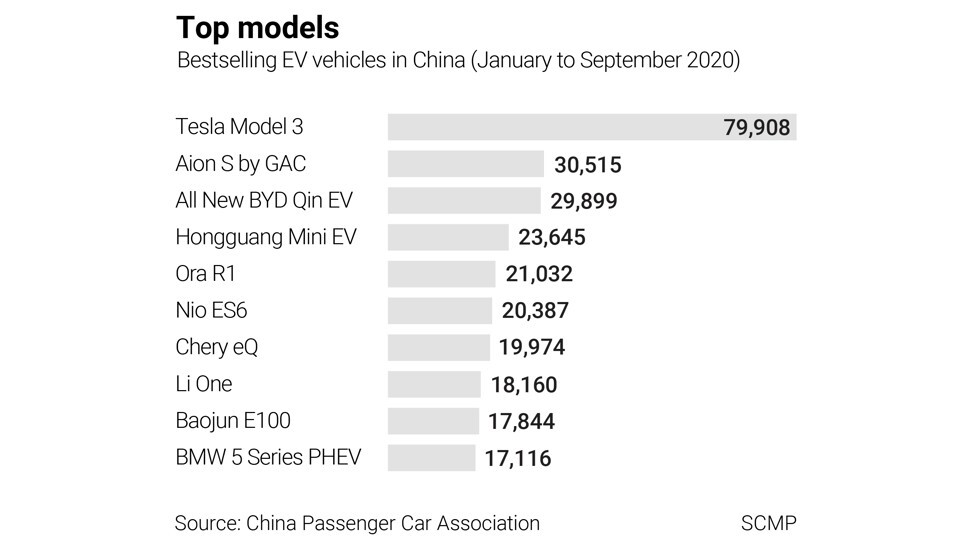

An assembler of cheap compact cars and minivans running on internal combustion engines has emerged as the unlikely victor – at least for the time being – in the vicious battlefield of the world’s largest market for electric vehicles.

“It is advisable for carmakers to work closely with local governments to facilitate [support services such as] number plates, access to parking and charging, and offer customers preferential electricity tariffs,” to support the growth of new-energy vehicles (NEVs), said SAIC-GM-Wuling’s marketing director Zhou Xing, adding that the robust sales data underscores the importance of working with local authorities. “A sound ecosystem is important in third- and fourth-tier cities as well as rural areas.”

Still, the success of the three-door compact car points to a greenfield market available to traditional carmakers in their battle with technology start-ups: rural China, inhabited by four in 10 people in the world’s most populous nation. By offering half of a Model 3’s standard range for 11 per cent the sticker price, the Hongguang is a vanguard of sorts in bringing electrification to farmers, villagers and small-town residents in China.

SCMP Infographics: What is a city tier in China, and how is it assigned?

The average budget among car buyers in rural China was below 70,000 yuan this year, mostly clustered around 50,000 yuan, according to a May survey by China EV 100, an industry alliance of assemblers, battery makers and charging station operators. With that budget, they require a driving range of between 100 kilometres and up to 300 kilometres, according to half of the respondents quoted in the survey.

Wang Qingliang, who lives in Pingdingshan in central China’s Henan province, would be a typical rural customer. The city of 5 million residents is best known as a producer of coal, gypsum and cement. Wang needs an electric vehicle that can drive at least 500 kilometres on a single charge, he said.

“For me, it is a 400-kilometre drive from my home to a county-level city, and those models in the government’s list do not suit me,” he said. “I cannot afford a high-end electric car with longer range.”

Access to charging stations is the first and foremost concern for many would-be electric car owners.

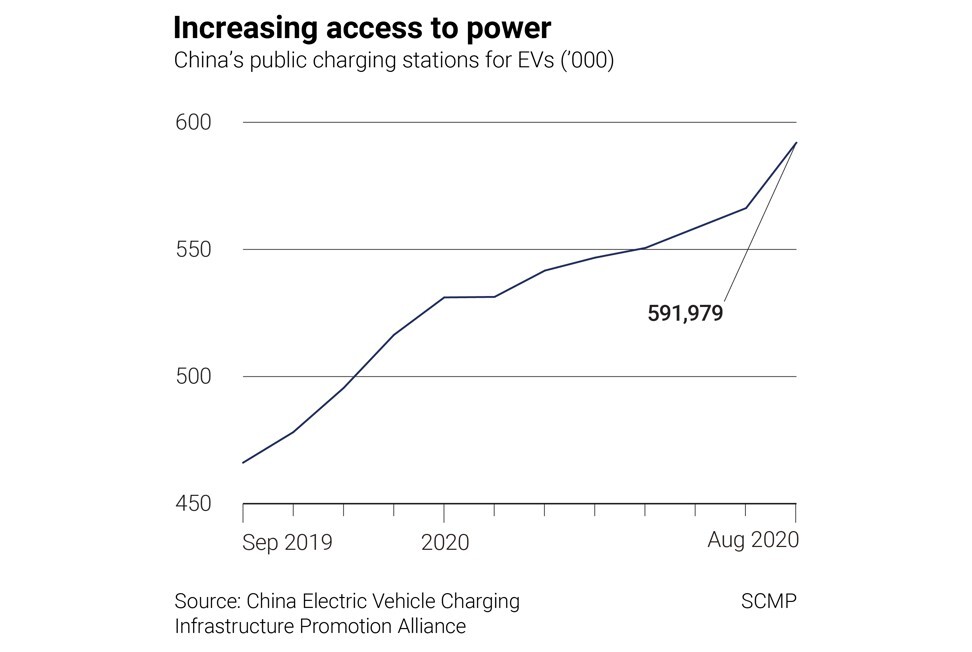

China had 1.2 million NEV charging stations, and is looking to add another 600,000 of them under a US$1.4 billion infrastructure stimulus package announced in April.

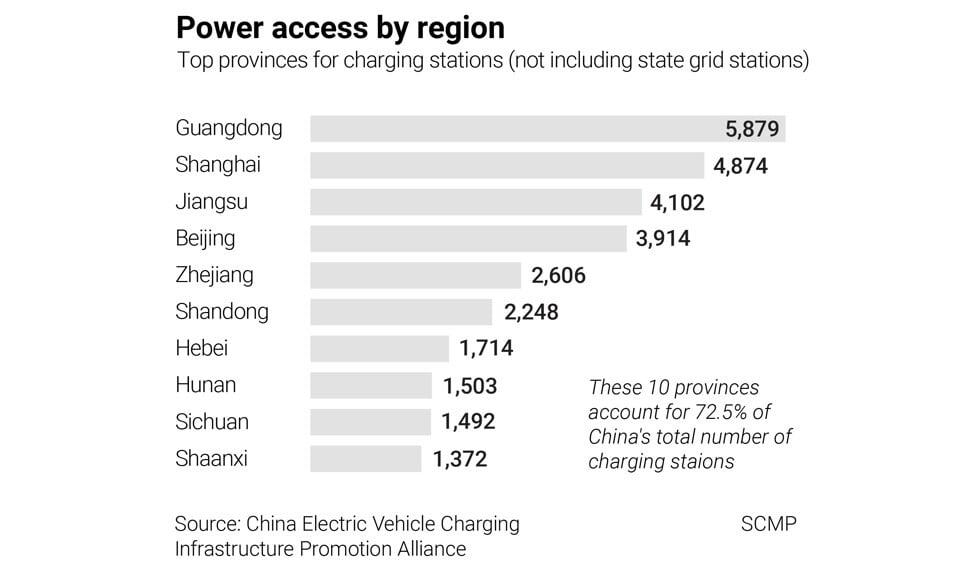

However, 72.5 per cent of public charging stations are concentrated in only 10 of the most economically developed regions, including the municipalities of Beijing, Shanghai, and the provincial capitals of Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, Anhui, Hebei, Hubei and Henan, according to data by the China Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Promotion Alliance. The figure proves that there’s a lack of motivation among public investors in expanding charging infrastructure in economically underdeveloped areas.

Charging stations require heavy initial investments with long-term paybacks, anywhere from five to 10 years, said Hong Kong-based credit rating agency Pengyuan International’s associate Danny Chen, who focuses on the automotive industry.

“The key issue for building up a charging station is it’s difficult to make a profit,” said Chen. “So far, we have not seen a clear business model that can keep a charging station operator profitable. Most NEV drivers in China will choose to [charge their vehicles] wherever is the cheapest, so [the usage behaviour] squeezes the profit margin of the business. Only stations with great locations can [expect] good profit.”

China had as many as 300 companies operating charging piles in 2017, when the government began its drive to promote electrification in automobiles. By the end of 2019, half of these have either shut down, or been taken over, while 30 per cent of them are still struggling to break even, said Zhao Jian, brand manager of TELD, a top Chinese charging pile maker, during an auto forum in January. TELD, the largest private operator of charging piles in China, turned profitable only in 2018, four years after its establishment.

Therein lies the chicken-or-the-egg question. More NEVs on the roads increase the demand for charging piles, which enable operators to attain the economics of scale to become profitable, but a wide network of charging stations is needed before electric cars can become common place.

“We do not build charging piles or stations in rural areas because those will sit in the dust,” said Zheng Xieyi, senior vice-president with Star Charge, which operates 270,000 charging points, with a 3 billion yuan investment plan to roll out an urban backbone network.

“Most NEV drivers in the rural areas just need a [step-up] transformer” to convert household electricity from 220 volts to the 380 voltage needed in electric cars, Zheng said. “The key to sustaining a healthy business is to follow the footprint of NEV makers.”

The biggest challenges – and costs – in building charging stations are the land for the premises, and investments to expand the capacity of the electricity grid. Charging equipment itself makes up only a third of the total costs, according to a research report by Rocky Mountain Institute, a non-profit organisation that specialises in energy policy.

“Paying attention to the charging needs of the vehicle segment is important to ensure the infrastructure meets the needs of the market,” according to the report. “Doing so can help not only the economics of electric vehicles, but also the economics of the infrastructure itself.”

That’s where the government comes in, laying the groundwork for the rudimentary charging network for operators to achieve scale, leaving the market to private companies to compete. The construction of infrastructure in the rural and underdeveloped areas is under way involving both the state and the private sector, in line with the government’s directives, said Zhi Zhibang, chief executive of LHC New Energy, a charging service solution provider which currently serves 100,000 EV users.

State Grid of China, the country’s largest electricity distributor, has pledged 2.7 billion yuan to build 78,000 charging stations across 18 provinces, with two-thirds of them earmarked for residential compounds, while 18,000 of them will be located in public space for shared use. China Southern Power Grid, another state-owned utility, said it would invest to build stations with 380,000 charging points over the next four years.

Charging infrastructure aside, China’s price-sensitive consumers also have hyperactive hip-pocket nerves, particularly in rural communities with lower incomes.

“Urging [manufacturers] to go rural is one thing, enforcing it is another issue,” said Luo Lei, deputy secretary general of the China Automobile Dealers Association, the industry’s main guild. “More fiscal subsidies for rural buyers are certainly essential, because most farmers are in the low-income group, most of them are more price sensitive.”

A proper understanding of the diversity in China’s automotive market is important for carmakers to design proper products that can attract customers, analysts said.

After a rocky start this year due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the industry showed signs of recovery over the past five months.

“I am a fan of Tesla, but I cannot afford it,” Wang said. “So I have to look at the mid-range products and hope that the car companies can quickly raise their production volumes to lower retail prices.”