Shipping lines face troubled waters as oil tankers, container carriers and cruise lines stop calling on China for fear of catching the coronavirus

- Port calls by container carriers fell 30 per cent in February, from a year ago, according to Clarksons

- Oil shipment to China from the Middle East fell to 12 per cent of what it was a year ago on February 5

Port calls to China are becoming less frequent, as fear of catching the coronavirus and a slowdown in the Chinese economy have deterred cruise liners, container ships, oil tankers and bulk carriers alike from stopping at the country’s harbours.

The coronavirus outbreak, which has sickened more than 75,000 around the world and killed more than 2,400, is adding to the woes of an industry that is already suffering from the US-China trade war. As many as 600 of the 3,700 passengers on the cruise ship Diamond Princess – moored in Yokohama outside Tokyo – contracted the virus while in close proximity to one another, which further deterred vessels from calling on mainland China, where more than 99 per cent of confirmed afflictions and deaths are.

As China’s labour force returns to work in phases after an extended Lunar New Year holiday imposed by the government in an effort to contain the epidemic, shipyards are slowly ramping up construction.

Still, vessel owners expect delivery to be delayed. Nine of the 19 Chinese shipyards surveyed by Clarksons put their yards on complete suspension on February 14, with none at full production.

“We foresee the delay to be between one to two months, depending on the capability and resilience of different shipyards,” said Zhou Jian-Feng, managing director of Wah Kwong Maritime Transport Holdings, which has two ships under construction at Chinese shipyards, and has several other projects underway.

Trade shows and business meetings are likely to be postponed, which means that there will be fewer building contracts signed in the short term, according to Daejin Lee, maritime analyst for IHS Markit.

Apart from the delivery delay, China’s vessel owners and shipping lines are facing difficulty finding crew, as sailors and officers from mainland China must follow quarantine regulations that apply at every port call, adding complexities and delays.

China is the second-biggest source of maritime crew, behind only the Philippines, and ahead of India, Greece and Eastern Europe, according to data by the Hong Kong Ship Owners Association (HKSOA).

China’s shipbuilding industry has exploded in size over the past two decades since the nation’s membership in the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and in the economic recovery since the 2003 outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars). China’s share of global maritime construction by tonnage almost tripled from 12 per cent in 2003 to 34 per cent by 2019, becoming the world’s largest shipbuilding nation.

Chinese shipping lines like Cosco and the financial leasing arms of the country’s biggest banks are collectively the second-largest vessel owners on the planet, which underscores their aggressive leasing activity over the past decade to carry the nation’s share of global commerce.

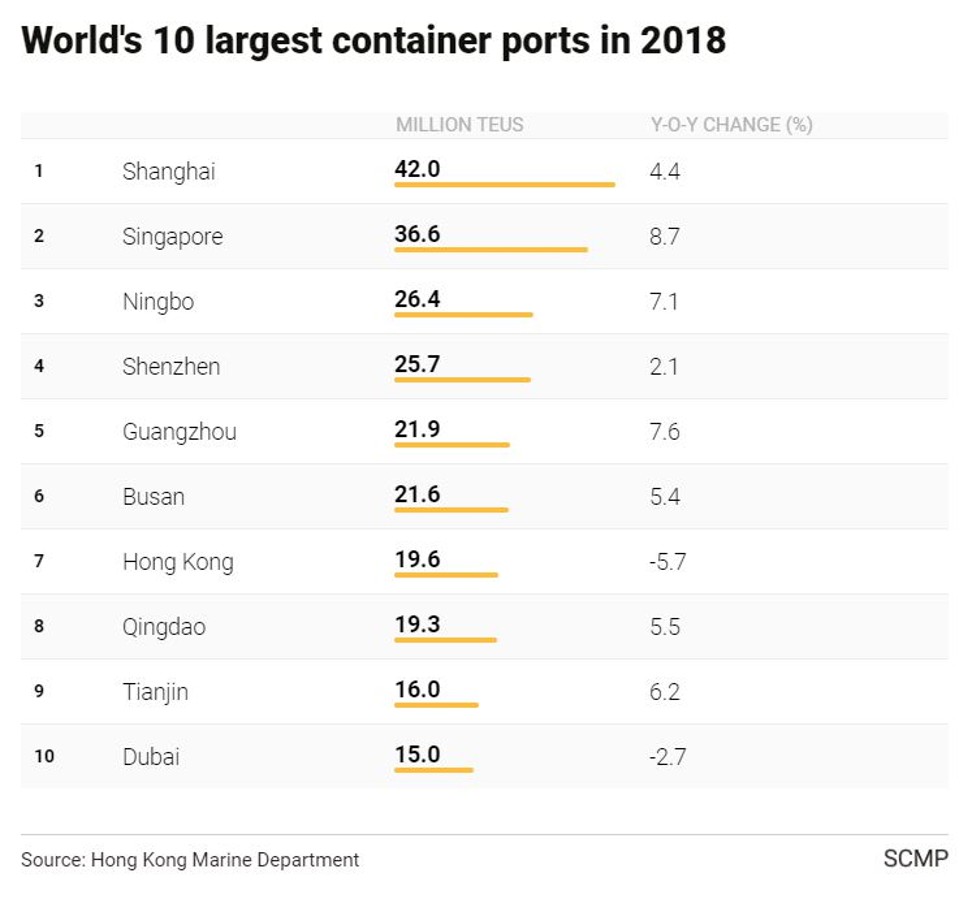

The world’s second-largest economy, China accounted for 14 per cent of all containerised cargo exports last year, 23 per cent of seaborne crude oil, 35 per cent of dry bulk shipped, 18 per cent of liquefied gas and 72 per cent of all seaborne iron ore.

That has taken a drastic turn, as the coronavirus outbreak gathered pace in February. Crude oil tankers have stopped sailing for China since the start of the month, compared with 3.42 billion ton-miles every day on average last year, according to satellite data provided by Vessels Value.

Shipments from the Middle East, China’s largest source of the commodity, were 280 million deadweight tonne cargo miles on February 5, a mere 12 per cent of the 2.32 billion DWT-mile shipped on the same day in 2019, according to shipping analytics firm Drewry, who note that global freight rates dropped 4.1 per cent in the second week of February, declining another 5.8 per cent this week.

That would put significant “stress” on port revenue if the low volume continues beyond March, because most European and Middle East ports have significant exposure to China, according to Fitch Ratings Agency.

Many of the world’s largest container shipping lines, including the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC), AP Moller Maersk, CMA-CGM and Hong Kong’s own OOCL have all cancelled sailings on their cargo routes from Asia to Europe and North America in recent weeks.

That would crimp global commerce, according to Clarksons data, as the research company cut its growth forecast of the world’s 2020 maritime trade to 2.2 per cent from an earlier estimate of 2.5 per cent.

The slower growth would affect harbour operators like Hutchison Port Holdings, a unit of tycoon Li Ka-shing’s CK Hutchison conglomerate. The company, the world’s largest operator of container ports including the Kwai Tsing terminals in Hong Kong, will see “negative growth” in this year’s throughput, after last year’s 3 per cent decline, Moody’s Investors Service said on February 10.

The shipping industry has already struggled with the switch to low sulphur fuels as mandated by IMO 2020, which prohibits sulphur exhaust. Uncertainty about the availability of low sulphur fuels and their cost has led to a number of cargo lines to fit their ships with “scrubbers”, which remove sulphur from ship’s exhaust. Clarksons estimated that 77 per cent of all such refits were being done at Chinese shipyards.

Delays will cause headaches to shippers who bet on the cost benefit of scrubbers versus using low sulphur fuels.