Winter Olympics: how China is trying to make winter sports less elitist ahead of Beijing Games

- Chinese President Xi Jinping says Olympics mark opportunity to develop winter sports across society, from rich to poor

- But ‘bigger agenda’ could be to create pool of talent to win medals for China according to sports business expert

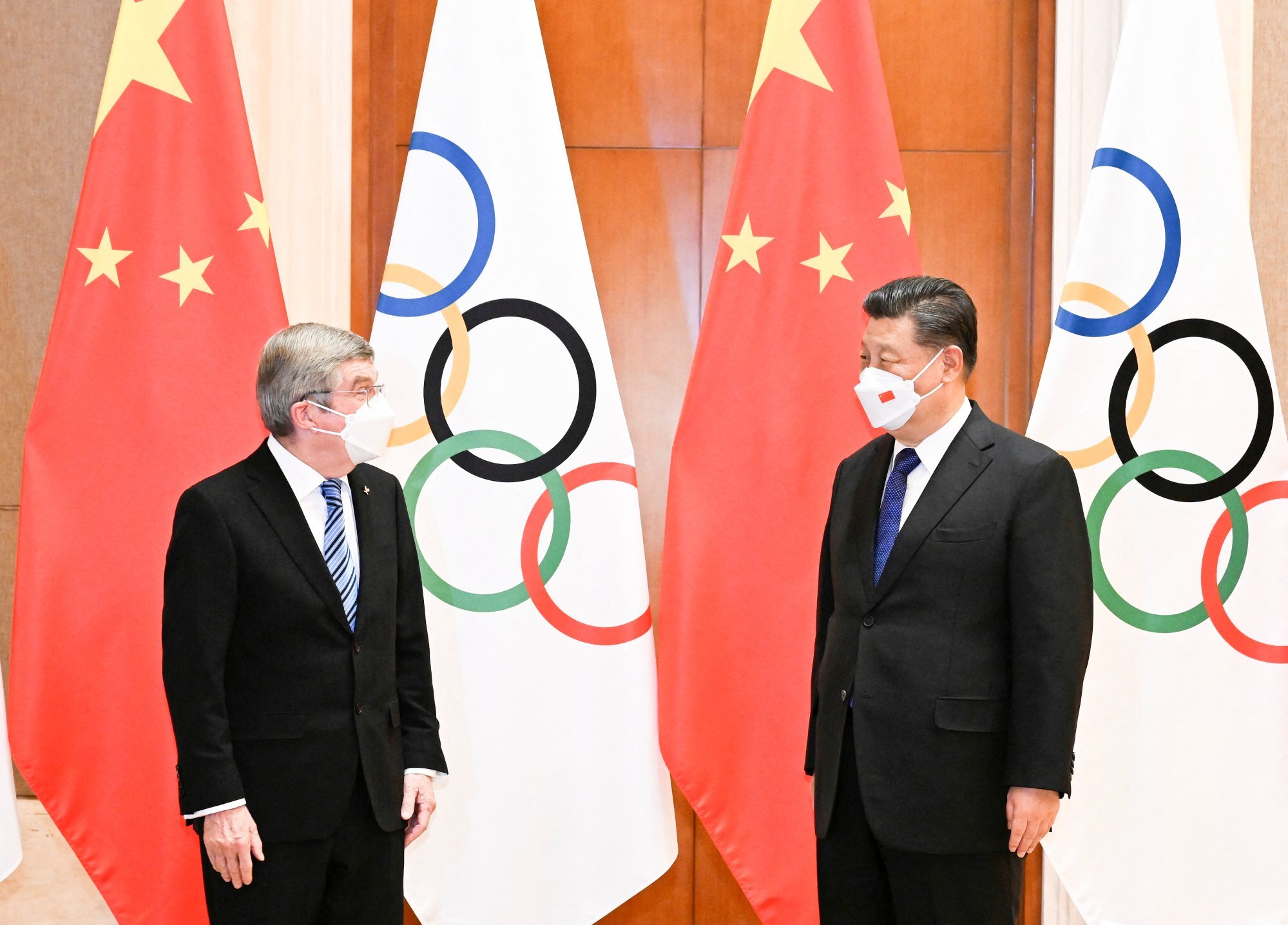

While unveiling plans for the Winter Olympics this month, Chinese President Xi Jinping said the event marked an opportunity to develop winter sports across Chinese society, from rich or poor.

“The enthusiasm brought about by Beijing 2022 should be maintained to promote the sustainable development of winter sports at both elite and grass roots levels,” Xi said, quoted in People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of China’s Communist Party.

The goal to increase “grass roots” involvement in winter sports may seem surprising precisely because these activities are known to be expensive. Purchasing the necessary equipment, along with travel costs and training lessons, is often out of reach for those with lower incomes.

Research conducted by Beijing Daily placed the cost of buying beginner’s snowboarding equipment – such as a snowboard, snowboard boots, and a helmet – between 3,000 and 40,000 yuan (US$6,300). In the same year, the per capita disposable income of residents in the country was 17,642 yuan, according to government figures.

From educating students about winter sports to supporting the development of ice skating rinks, China has led a variety of initiatives for snow sports to become more accessible to the general public, though some have questioned the usefulness of these efforts.

In 2016, one year after Beijing secured its bid to host the 2022 Winter Olympics, authorities unrolled a “Winter Sports Development Plan” accompanied by a “National Plan for the Construction of Winter Sport Venues and Facilities” that listed, among other measures, investing 1 trillion yuan (US$148 billion) into the winter sports industry by 2025.

Beijing launched a follow-up plan in 2019 that listed a key goal of increasing China’s total number of winter sports participants from 12 million to more than 300 million by 2022.

The participation goal was achieved in January this year, with more than 346 million people in China taking part in winter sports activities since 2015, according to figures released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Most participants lived in East China (143 million), with 51 million in the much colder northeast, indicating the interest generated was from regions with less snowfall. The movement of visitors reflects additional data released by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as 254 million winter sports-related trips were made in 2021, with an additional 305 million trips expected in 2022.

However, while touting its statistics, the bureau did not specify what constitutes participation, only stating that more than 86 per cent took part in winter sports “either for entertainment or physical exercise”, with 93 per cent of participants taking part “spontaneously”.

Hans Westerbeek, professor of international sport business at Australia’s Victoria University, said that participation in winter sports may not necessarily mean they have become more accessible.

“Discounting those in China who cannot afford to travel and buy equipment and tickets … it is quite an elitist activity,” said Westerbeek, who heads his university’s sport business insights group.

“It takes a lot of time, effort and resources to get engaged. If this is about getting people more active, there are a lot of options that are easier and cheaper.”

Westerbeek added that since those engaging in winter sports “must be the middle class and above”, Beijing’s motives for the push remain unclear.

“The bigger question is, is it really the central government’s task to focus on winter sports? Or is the bigger agenda to get a pool of winter sports talent ready to win medals at the Winter Olympics for China?”

China’s delegation at the Winter Olympics has increased over the past three Games. It sent 66 athletes to the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, and 88 athletes to Pyeongchang 2018.

This year’s delegation – China’s largest at a Winter Games – will feature 176 athletes, who have won a total of 11 medals, five of which are gold.

In turn, facilities serving competitive and recreational use have boomed, both as a result of government construction and the private market. As of January this year, China now has 654 standard ice rinks, an increase of 317 per cent from 2015, and 803 indoor and outdoor ski resorts, up from 568 resorts in 2015.

The increasing interest in snow sports has also prompted a boom in the ski industry, which may point to a wider variety of options for winter sports equipment. The market for ski equipment alone expanded from 3.22 billion yuan in 2014 to 12.69 billion yuan in 2020, according to a report released last December by Zhiyan Consulting.

A long-term strategy for China’s growing winter sports market could involve lowering existing barriers, according to Allison Malmsten, marketing director at Daxue Consulting, a Shanghai-based market research firm.

“The market for second-hand equipment could develop as the winter sports market matures, which gives the lower-class access to quality equipment at a more affordable price,” she said.

“A lot of the focus has been on skiing and snowboarding, but there are other winter sports that are not as expensive. Skating is one sport that has a lower financial barrier to begin [with], as it requires much less equipment and cheaper access to rinks.”

Trying to make sure that people from different backgrounds can compete in sports is also important to Sidney Chu, a short-track speed skater who will represent Hong Kong at the upcoming Games.

With support from the Hong Kong Sports Institute, which provides stipends for athletes depending on their competitive grade, Chu said that speed skating became “more bearable and realistic”, as the Institute would foot the bills for ice time and coaching.

Skating, he noted, was more economical, since coaching could be done in groups.

“I think that’s a beautiful thing about speed skating in Hong Kong and why it’s worth investing [in] because it’s not just something that [children of rich people] can learn,” he said. “It’s something that all Hong Kong people can enjoy in the future.”