Advertisement

Advertisement

Winston Mok

Winston Mok, a private investor, was previously a private equity investor. He held senior regional positions with EMP Global and GE Capital, and was a McKinsey consultant and initiated its China practice. Winston obtained his bachelor and master degrees from MIT.

For Brics nations to secure global reforms, they must build effective institutions, protect property rights and strengthen the rule of law.

As China’s Gen Z opt for more experience-based consumer choices, policymakers must step in to help them support the traditional economy too.

Protectionism won’t bring back lost jobs. It will just push companies to move production to places where supply chains are intact even if costs are not the lowest.

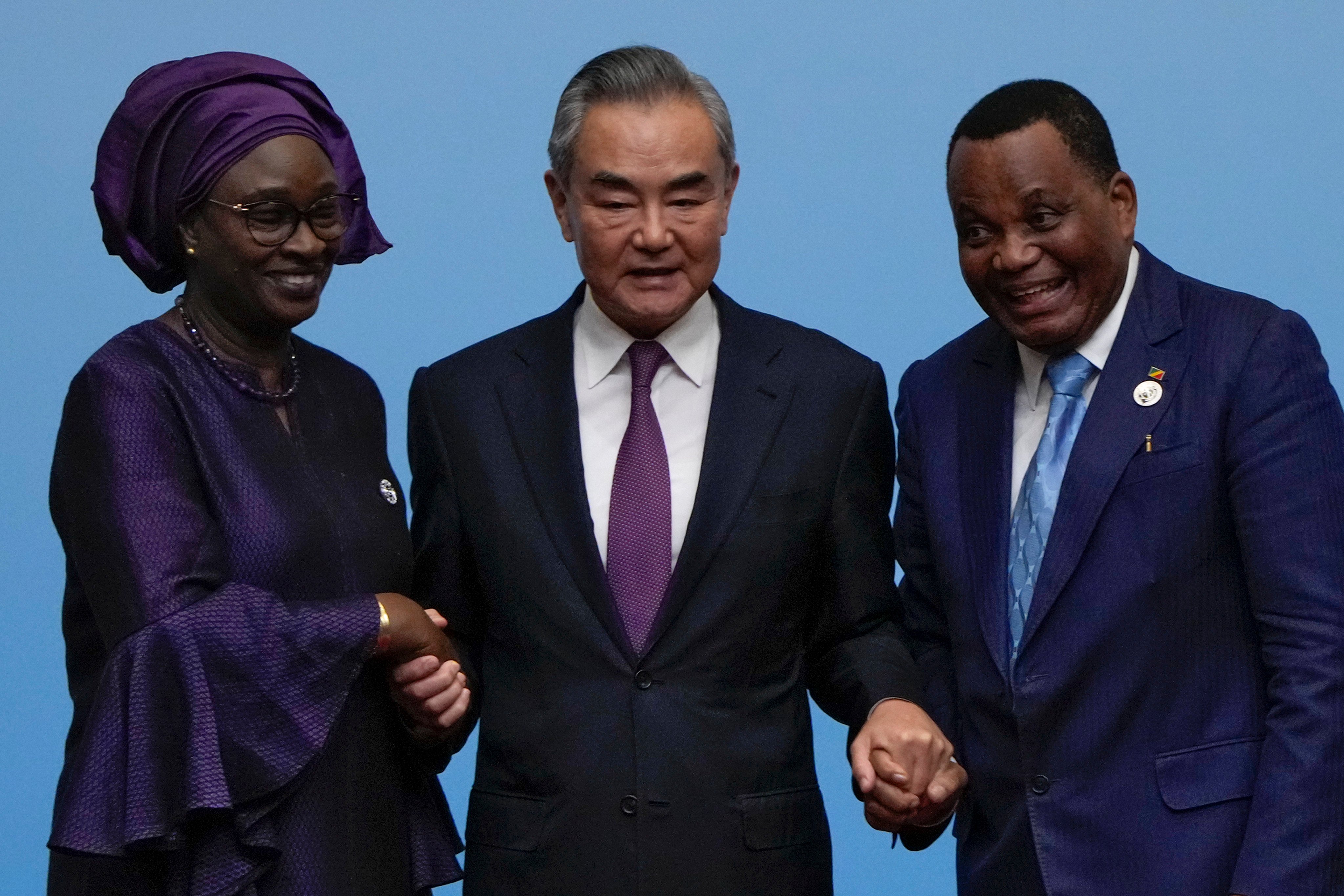

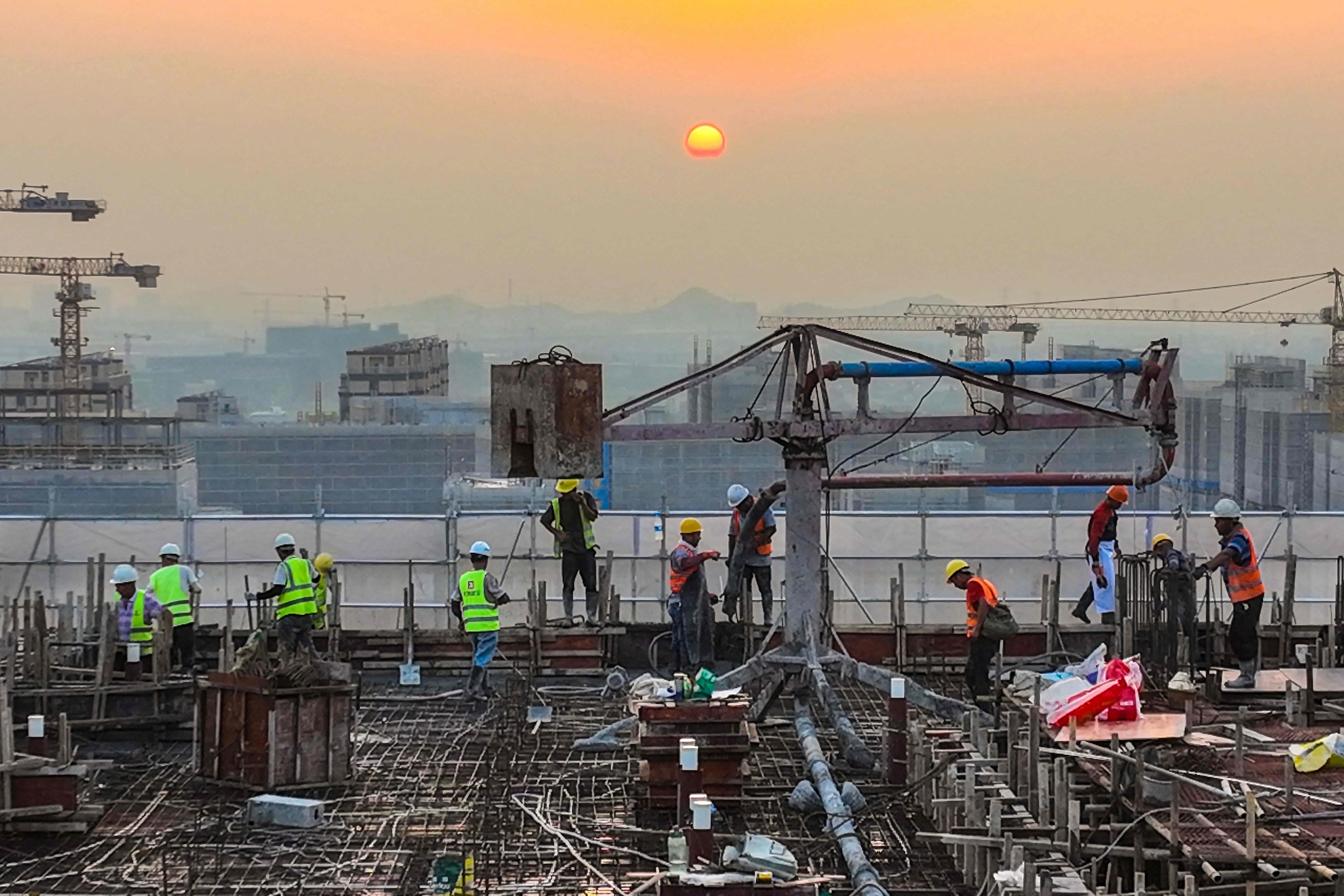

Where once China was a source of infrastructure and financing, Africa will now look to Beijing for knowledge and guidance on industrialising.

Advertisement

Whether it’s industrialising, fighting tuberculosis or improving child nutrition, the bloc of nations around the Bay of Bengal would benefit from Sino-Indian cooperation.

While ostensibly a showcase of athletic prowess, the Olympics reveal deeper socioeconomic dynamics at play globally.

With a shift away from disproportionately expecting state governments to power growth, the focus must now be on social welfare and stability.

The US market may be closed to it but China can shape development in Africa – as a developer and operator of solar energy projects.

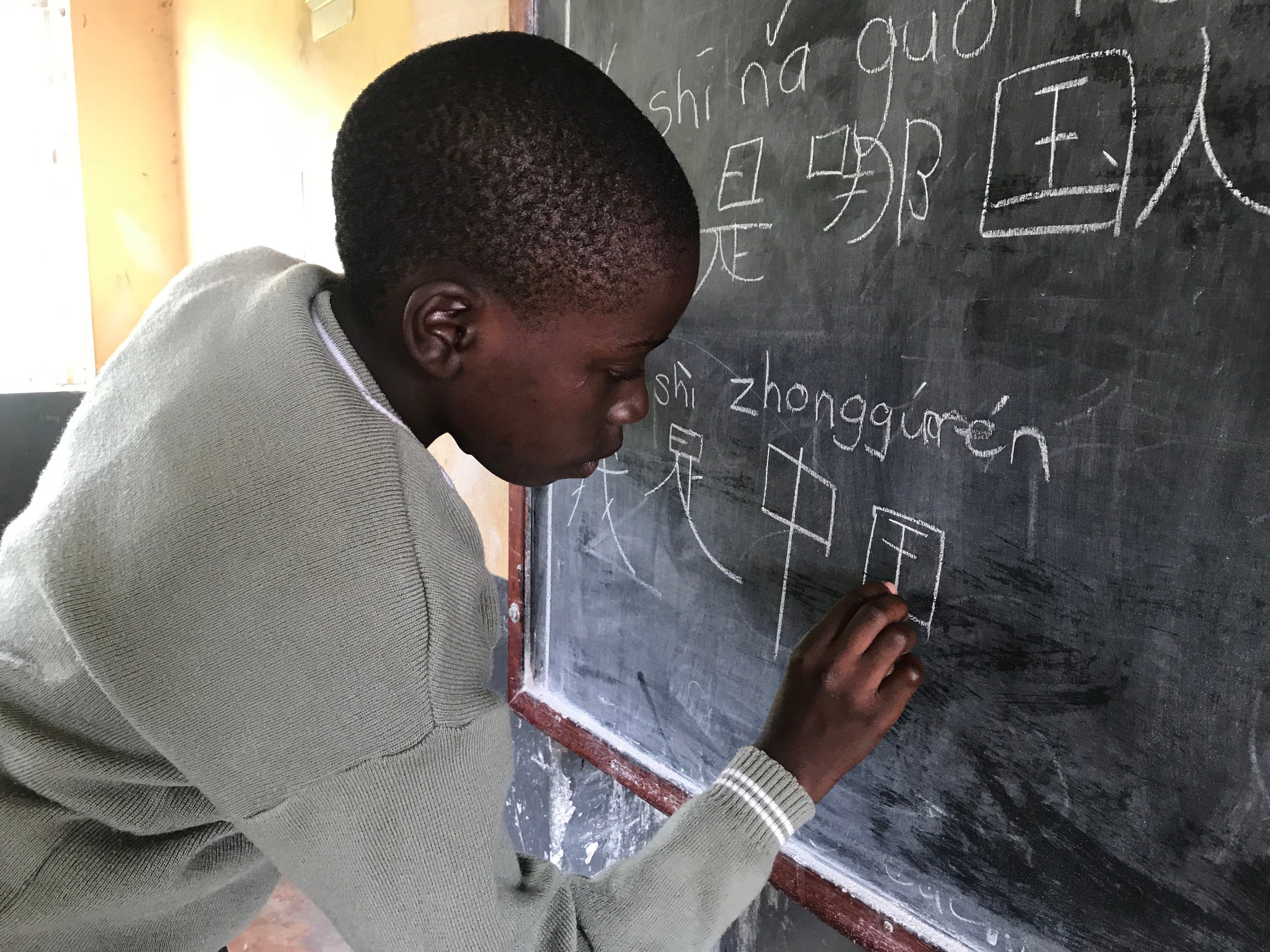

Instead of imposing Chinese language education as a barrier, the city must adopt inclusive reforms that allow minority students to thrive

History and economics are both challenges and the ties that bind for the three neighbours, which are all vital nodes in the semiconductor supply chain.

China’s inter-regional rivalries and US inter-party politics are colliding in the fight for global electric vehicle dominance, pushing the world towards a future of walled camps engaged in escalating mercantilism while putting our common destiny at risk.

As Chinese multinational firms expand their presence internationally, they can reshape global production networks towards the Global South and accelerate the transition to a green economy, helping build a more sustainable future for all.

Despite US fears about an overcapacity in Chinese green teach, China’s market share of solar modules and electric vehicles is smaller than that of other competitors. “Cooperative competition” between manufacturers can help both countries synergize their green industry transitions.

As major investors displacing the traditional Western powers, China and the GCC are precipitating a reconfiguration away from the North-South flow of development resources.

While the US is mired in infrastructural challenges and market inertia, China offers a supportive EV ecosystem and a multimodal transport system in which EVs can thrive.

The Western semiconductor landscape is an intertwined global network, fostered by decades of collaborative research and intellectual property sharing. Beijing must learn to marshal its domestic and international resources in a similar way to realise its ambitions.

The middle class has long been seen as the core of China’s future prosperity, but a depressed stock market and home values are sapping their confidence. The nation is at a critical juncture when effective reforms are needed to channel the energy of the middle class into driving economic recovery.

From pensions to medical care, China’s rural-urban divide must be urgently addressed. Or just about everyone outside the rich middle class will be left out of the silver economy.

The post-pandemic trend of the young and mobile increasingly moving out of China’s megacities is shaping the direction of the country’s urbanisation and regional development.

A full transition to a rules-based society will help Beijing restore the confidence of businesses and citizens in its ability to weather the economic storm. To root out corruption, China must put its faith in institutions with accountability, not endless anti-corruption campaigns.

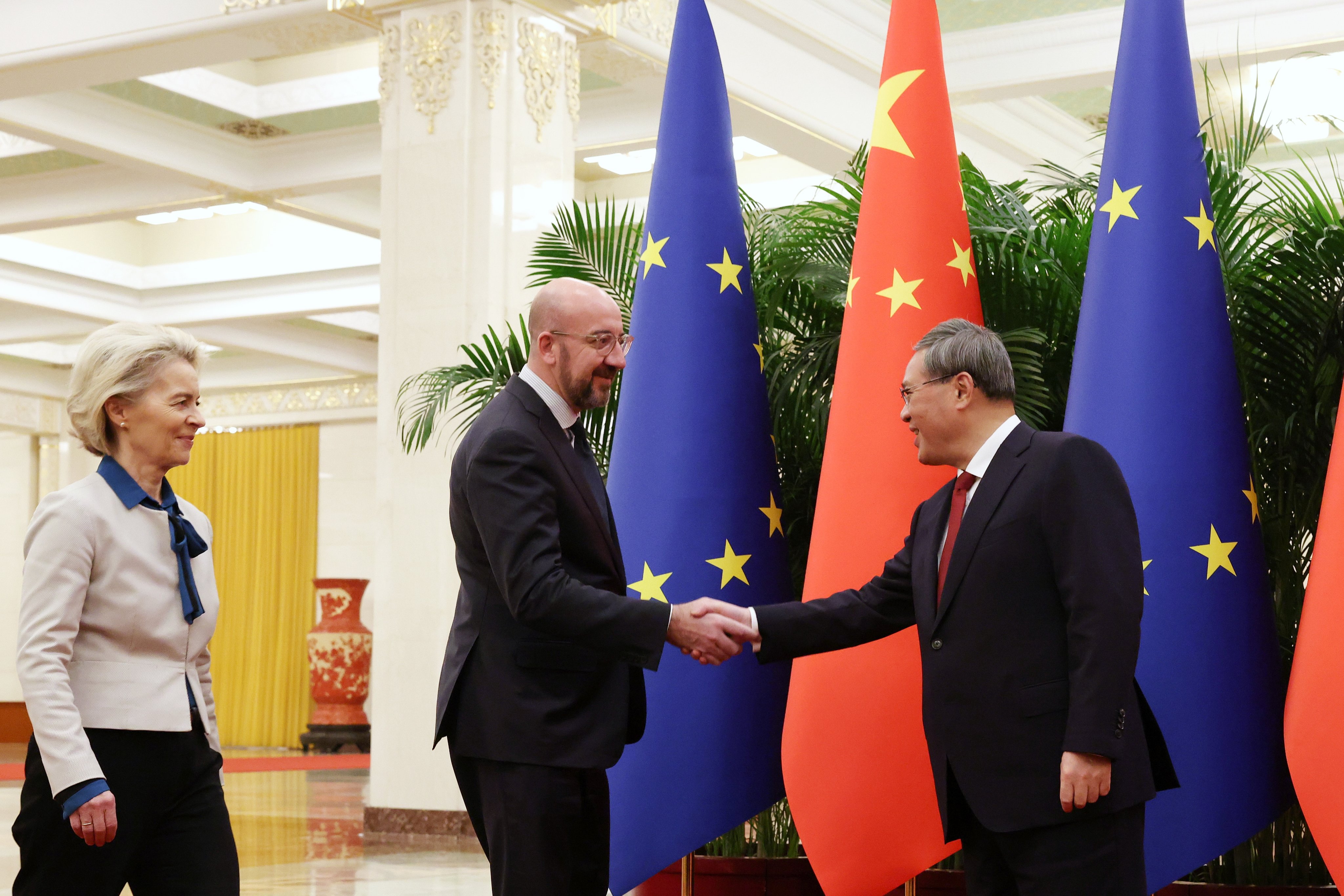

There are vast differences between China and the European Union despite recent warm rhetoric, but these can be overcome with greater cooperation. Beijing can help rebuild trust by addressing Brussels’ concerns over exports to Russia, improving market access and working together on shared issues in Africa.

Pledges of reform from a decade ago have been unfulfilled or unevenly implemented, leaving China’s economy struggling to reach its full potential. Leaders should look to the legacy of Zhu Rongji, who embraced bold but unpopular reforms to improve people’s well-being.

China’s edge in EV production is based on many competitive advantages, but work is needed if it’s to be turned into an engine of growth. Realistically, its EV makers must look beyond the US and Europe to other emerging markets for expansion. Here’s where the belt and road can play a key role.

Beyond a corruption crackdown, a structural reconfiguration of the healthcare system would unleash the consumption long suppressed by the need to save for costly medical bills. It would also build confidence, improve social stability, boost the government’s standing and, perhaps, even encourage births.

Policymakers have enacted easing measures for China’s property sector, but the impact is likely to be limited and fail to address underlying causes. Looking to the Singapore model of social housing could be the best way to get China back on track.

Amid falling corporate trust and a US tech barricade, creative solutions are needed, such as setting up centres of collaboration in trusted third countries like Singapore.

The capital city must improve its coordination with nearby Tianjin and Hebei, and look to the Greater Bay Area tech cluster for lessons. China must also establish outposts of innovation overseas.

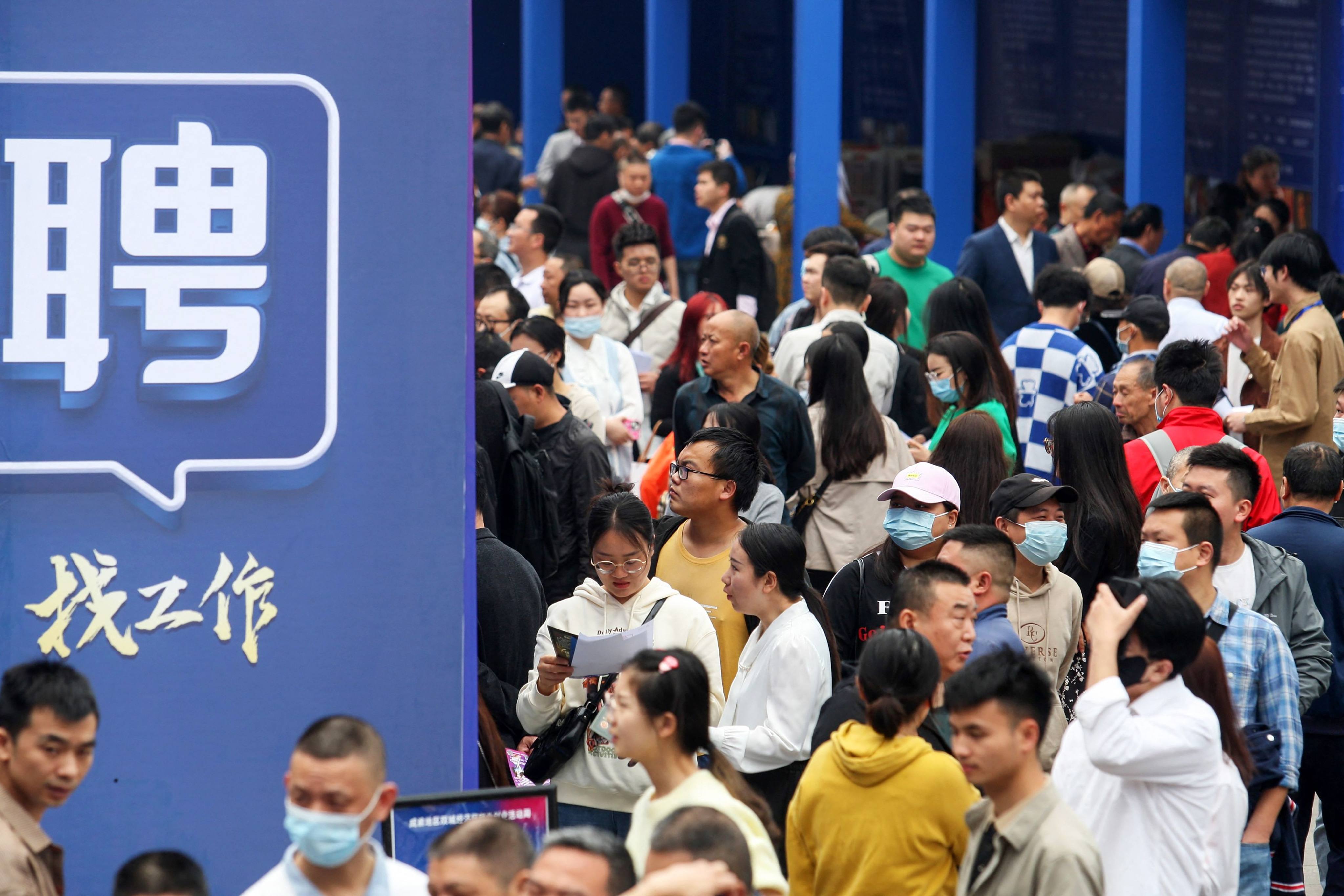

In a tough job climate, some young Chinese are ‘lying flat’, ‘letting it rot’ or considering leaving the country. Recent regulatory clampdowns on sectors like tutoring have not helped job prospects. To solve the problem, the government should listen to young people.

The defence of free expression, danger of losing youth voters and risk of hitting small businesses could be enough to block a ban. Beijing could also help by amending its laws to explicitly prohibit requests for transfers of overseas data.

China’s foremost development challenge is in innovation, but more pervasive party leadership may not produce the best results. Hong Kong, however, with its uniquely encouraging institutional environment, can become China’s innovation hub