Philippines’ Marcos Jnr has been rebranding himself as a human rights supporter. Is it working?

- Marcos Jnr’s pro-US stance and measures to ‘elevate’ the Philippines have made him a ‘pivotal player’ on South China Sea issues among world leaders

- Critics say Marcos Jnr’s rebranding efforts could lead to actual human rights movements losing support and legitimacy

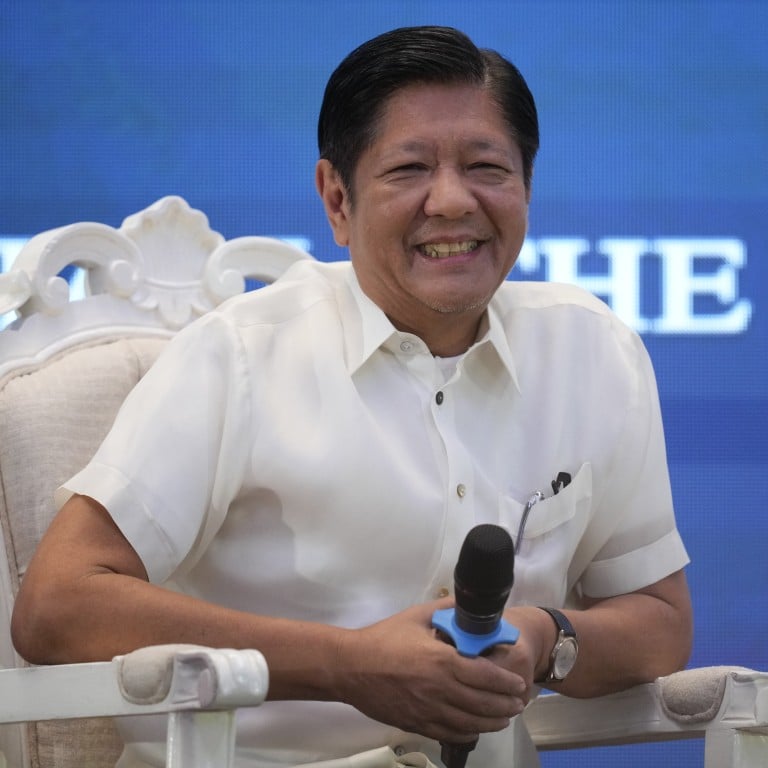

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr’s efforts at rehabilitating his family image and rebranding himself as more pro-human rights than his predecessor look to be paying off, after Time magazine included him in its list of 100 Most Influential People of 2024.

The magazine’s write-up said Marcos Jnr had “elevated the Philippines on the world stage” through a number of measures, including a more technocratic administration, steadying the economy and strengthening its alliance with the United States to counter China’s aggression in the South China Sea.

Cleve Arguelles, a political scientist and head of polling firm WR Numero, told This Week in Asia that Marcos Jnr’s inclusion was hardly surprising, noting the Philippine president’s positive reception from the international community since his election in 2022.

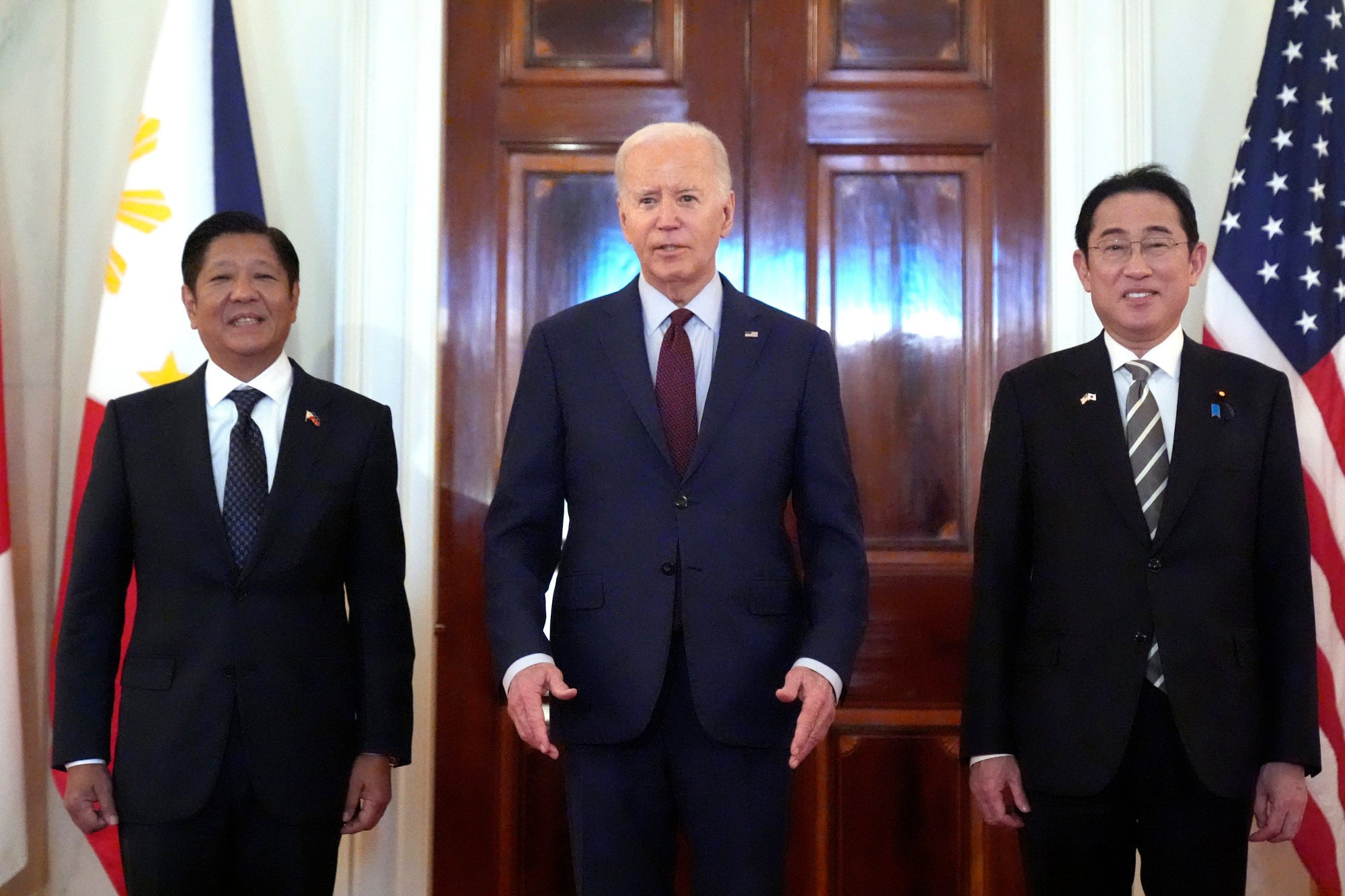

Arguelles said the recent trilateral summit between Marcos Jnr, US President Joe Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida – which focused on strengthening their defensive capabilities in the Indo-Pacific region amid Manila’s maritime disputes with China – had placed the Philippine president in the international spotlight.

“He’s seen as a very pivotal player on this issue about China, and that occupies a lot of mental space among world leaders,” Arguelles said.

Countries such as the US were encouraged to boost Marcos Jnr’s image on the international stage out of geopolitical convenience, he added.

“No one else in Southeast Asia is so pro-US now [than the Philippines]. That speaks to the US’ insecurity in the area because they badly need a reliable ally in this part of the world because of China,” he said.

Marcos Jnr’s US-friendly stance is in stark contrast to former president Rodrigo Duterte, who realigned the country’s foreign policy towards China and stayed largely quiet about Beijing’s expansionism in the South China Sea.

The current president has also distanced himself from his predecessor’s controversial war on drugs, which rights activists say led to the extrajudicial killings of more than 12,000 Filipinos during Duterte’s administration, mostly among urban poor.

Following a drug bust on April 15 in which authorities confiscated 13.3 billion Philippine pesos’ (US$231 million) worth of methamphetamines, locally known as shabu, Marcos Jnr said: “This is the biggest shipment of shabu that [we’ve ever] intercepted. But not one person died. Nobody died. No shots were fired. Nobody was hurt.”

Despite this, drug-related killings have persisted since Marcos Jnr took office. According to a study from the University of the Philippines, as of April 15, 621 deaths have been recorded since he took office, 42 per cent of which were committed by state agents during anti-illegal drug operations.

Human rights defender?

The notion that Marcos Jnr is more concerned about human rights than his predecessor has gained significant credibility after two staunch critics of the Duterte government gave more favourable opinions about the current leadership.

Former senator Leila De Lima was politically persecuted by Duterte and jailed for more than six years over trumped-up charges before being allowed to post bail in November. In February, she said the Marcos Jnr administration had provided “breathing room” from Duterte’s “authoritarian regime”.

“Under [Marcos Jnr], we are given the opportunity to make use of a democratic space in transition from the authoritarian regime that was Duterte’s,” De Lima said. “This is a breathing room from the seven years of nightmare that we thought was all over in 1986 and never to return again. But it did.”

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa, founder of independent news outlet Rappler, said there appeared to be a “lifting of fear” for journalists since Marcos Jnr took office.

“There’s been a lot of problems in the Philippines because fear spreads. But [press freedom] has improved … Is it perfect? Far from it. We still have a lot of work to do,” she said.

Ressa was acquitted of a final tax evasion charge in September. Press freedom advocates had decried the charge against Ressa as being politically motivated by Rappler’s critical coverage of Duterte’s administration and drug war.

However, Arguelles said there was danger in over-celebrating the “bare minimum” that the Marcos Jnr administration had achieved in terms of human rights.

“If the US and Western leaders are doing this out of geopolitical convenience, I think the danger is that [locally] we do this out of convenience because we want to get rid of the Dutertes. We end up legitimising the Marcoses. But we have to be reminded that they are not friends of democracy, human rights, and liberal values in the Philippines,” Arguelles warned.

Marcos Jnr has repeatedly refused to apologise for the well-documented human rights violations that occurred under his father’s 21-year martial law regime – including rampant corruption and the targeting of political opponents, student activists and journalists.

Critics say his presidential campaigned utilised misleading propaganda to rewrite that history in the minds of voters.

Athena Charanne Presto, a sociologist from the University of the Philippines, said Marcos Jnr’s new-found image as a human rights supporter could lead to legitimate human rights movements losing support and legitimacy.

“[Marcos Jnr’s] narrative during the election was that his family was a victim of history by people in power. Because you have that powerful narrative legitimised, others such as those in the impoverished sector, young people who feel they are voiceless in Philippine society, may find themselves relating to that. For martial law victims, it can be difficult to compete with perceived marginalised voices, like the Marcos family competing with their narratives,” she said.

Political dynamics

Arguelles said Marcos Jnr’s efforts to rebrand himself could be about widening his support base, with his relationship with Duterte becoming increasingly antagonistic.

Duterte’s daughter, Vice-President Sara Duterte-Carpio, joined Marcos Jnr’s presidential campaign, uniting the supporters of both politically prominent families. In recent months, however, the president and his predecessor have been trading insults and accusations of drug use.

“[The Marcoses] know that they have to test new ideas, otherwise it’s going to be a problem for them. They know the Dutertes are a significant threat to them, and that they are kings and queens of using public opinion to their advantage,” Arguelles said.

However, Marcos Jnr’s attempts to revamp his image do not appear to be helping him win over the public. A Pulse Asia survey found his approval rating had declined from 68 per cent in December to 55 per cent in March.

Arguelles said the president must address domestic issues such as rising prices of goods, hunger and poverty, and jobs and economic opportunities to win back public favour.

“If you’re failing on the domestic side, I don’t think you can just use the international side to fill in that gap,” he said.

Meanwhile, Presto the sociologist said her work in youth politics showed young people remained critical of the president.

“[They are] saying things such as, ‘I will believe it when [Marcos Jnr] legalises divorce, when [he] legalises same-sex marriage,” she said.