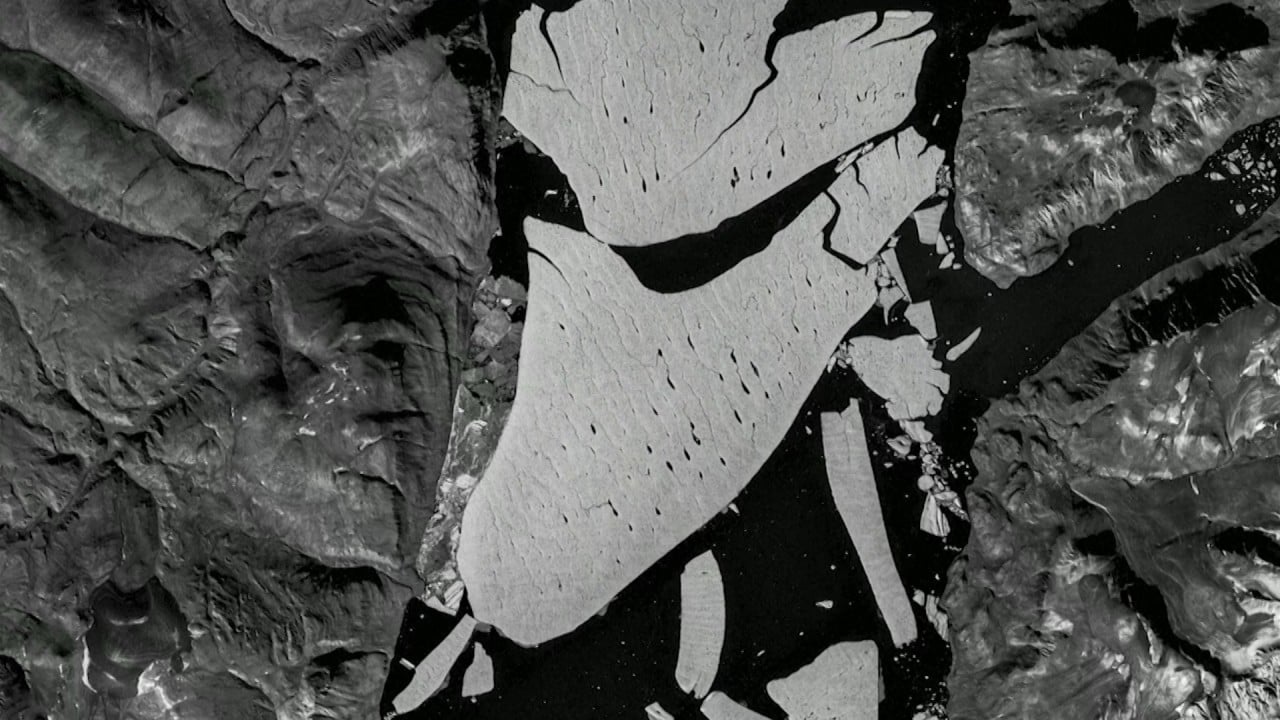

Will Russia sanctions freeze Asia’s climate change research on the Arctic?

- A suspension of the Arctic Council’s activities amid the Ukraine war means research collaborations between polar nations and Asian states like Singapore, India and Japan, will be put on ice, analysts say

- Amid concerns over issues such as the effects of melting ice on global shipping routes and trade, one observer says a Euro-Asian-Arctic arc of cooperation may be needed

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine halts research activities in the Arctic region, Asia’s bid to tackle climate change will become a casualty, analysts say, which may push them to turn to non-governmental organisations to address environmental issues.

A week after Moscow invaded Ukraine, seven of the eight Arctic states registered their opposition to the war by announcing they would suspend their participation in all meetings of the Arctic Council and its subsidiary bodies.

The premier forum for Arctic governance includes Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States.

Nikolay Korchunov, Russia’s ambassador-at-large to the Arctic Council, called the move “regrettable” and said it was contrary to the apolitical nature of the intergovernmental forum founded more than 25 years ago.

Under the suspension, all scientific projects and research collaborations on sustainable development and the environmental protection of the Arctic will discontinue.

Russia-Ukraine war upends hopes for global climate action

Marc Lanteigne, associate professor at the University of Tromsø in Norway, said the suspension came at a “poor” time given the worsening climate change situation in the polar regions and the effect on local communities.

Uncertainties about energy prices and supply chains worldwide have also fuelled anxieties, he said, noting that a longer-term split between Russia and the West may “open the door for future environmental degradation”.

Malte Humpert, founder and senior fellow at The Arctic Institute’s Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, said for the past 25 years, Arctic states had relied on the Council to coordinate research activities and develop new policies and regulations to safeguard the Arctic Ocean from oil spills and shipping emissions, among others.

“If the Arctic Council remains frozen permanently, new avenues for cooperation, at least among the seven Arctic states, will have to be found,” he said.

Klaus Dodds, professor of geopolitics at the University of London Royal Holloway, said the freeze was “deeply unsettling for an intergovernmental forum that prided itself as being a model of circumpolar, knowledge-sharing and indigenous-inclusive governance”.

“The reality of the situation is simple. Russia is the largest Arctic state, and 50 per cent of the Arctic’s land mass and population, respectively, is Russian,” Dodds said, adding that by pausing collaboration and exchange, Moscow’s shift to the east and south would be further accelerated.

“(This means) working with India and China on energy and infrastructure projects. India will use this opportunity to develop further a strategic dialogue with Russia,” said Dodds, who is also author of The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction.

Impact on Asia

The freeze on the Council’s activities is also expected to affect Asia, especially in combating climate change, analysts noted.

Five Asian countries are observers within the Arctic Council: China, India, Japan, Singapore and South Korea.

Aki Tonami, an associate international relations and economics professor at the University of Tsukuba, said given Russia’s large territory in the Arctic, efforts by these observer states in conducting scientific research would be affected.

Pointing out that data gathering and sharing remained key to climate change research, Tonami said it was unclear if Russia would allow other states to collect data in or around its territory, or whether countries would be willing to share information with Moscow.

The war had also thrown the Arctic Science Ministerial – an annual platform to discuss Arctic research and cooperation, attended by European, Arctic, and Asian observer nations – in doubt, Tonami said. This year’s event was to be co-chaired by Russia and France.

No wind, grey skies and a fossil fuel habit: Singapore’s climate puzzle

Lanteigne said the freeze on Council activities meant that “a major conduit of engagement and cooperation” would be closed off, since most work undertaken by Asian observer states was through the forum’s working groups.

“This will be especially difficult for some observers like India and Singapore, which have relied on the Council heavily to build their Arctic legitimacy,” Lanteigne said, adding that until the work of the Council was restored, observers would need to rely even more heavily on non-governmental organisations for regional engagement.

“For the short term, observer states will need to rely more heavily on bilateral relations with the other Arctic governments for their policy development in the far north,” he added.

Solving the climate crisis hinges on action taken in Asia

But Humpert said the suspension would have little impact on the Arctic priorities of Asian observer states as such status in the Council was limited to the participation in the working groups.

These groups are primarily focused on studying the Arctic environment such as marine pollution, land-based and sea-based emissions, the melting of permafrost, and Arctic tundra fires, Humpert noted.

“To be honest, the role of most observer states is quite limited,” Humpert said, with Germany being a notable exception given its status as an observer for 25 years.

Observer states contribute scientific expertise to working groups and then integrate the findings into their domestic research efforts, Humpert said, adding that if the Council remained suspended for years, some joint research projects that Asian observer states were involved in would have to find new “homes” under which they could be conducted.

“But by and large, the primary impact of reduced research activity in the Arctic Council will be related to Arctic-specific research most pertinent to the eight Arctic states,” Humpert said.

India

Last month, India released its Arctic Policy, with an eye on combating climate change by strengthening its cooperation with the resource-rich and rapidly transforming region, which is warming at three times the rate as compared to the rest of the world.

It hopes to help improve international response mechanisms, and wants to study the implications of melting ice on shipping routes around the world, energy security and the exploitation of mineral wealth.

Was climate change to blame for India’s glacier flood disaster?

The release of the policy means that India is hoping to gain greater visibility as an Arctic stakeholder, Lanteigne from the University of Tromsø said, adding that New Delhi’s initiatives would be affected both by the pause in the council’s activities and the “diplomatic chasm” that has opened between Moscow and the other seven Arctic governments.

While Europe and the US have cut ties with Russia over the war, India has not criticised or backed Western sanctions against Moscow.

Singapore

Singapore contributes to the climate change agenda by participating in high-level international Arctic events, and raising regional awareness of Arctic issues, according to a foreign ministry statement last year.

Apart from active participation in various working groups within the Council, the city state also shares best practices and knowledge in areas such as preventing oil spills, conserving biodiversity, marine shipping and sustainable energy development.

According to the Arctic Institute, Singapore’s interest stems from the Northern Sea Route’s potential challenge to the island state’s role as a global shipping hub, as well as from the consequences of the melting sea ice.

Rising sea levels plunge Singapore into battle to stay above water

The Northern Sea Route is the maritime route through the Arctic along the northern coast of the Eurasian land mass, principally situated off the coast of northern Russia.

“Singapore has been expressing concerns both about the changing shape of global shipping as the Arctic opens up to further sea trade, and because as a low-lying island nation, it is also concerned with the effects of polar ice melting on local sea level rise,” noted Lanteigne.

Japan and South Korea

Japan has emphasised maritime interests including security, while South Korea is focused on both maritime affairs and educational programmes linking Arctic and non-Arctic students and specialists, according to Lanteigne.

But the uncertainty over the development of the Polar Silk Road will affect Japan and South Korea’s plans for potentially using the waterway for trade, he said.

China last year announced it would construct a Polar Silk Road – shipping routes connecting North America, East Asia, and Western Europe, through the Arctic Circle – during its five-year plan that ends in 2025.

What next for China’s Polar Silk Road as Putin’s war sparks Arctic freeze?

As ice caps recede because of rising temperatures, Beijing has been eyeing mineral resources and new shipping routes in the Arctic regions. The Polar Silk Road concept is part of its trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative to expand its influence through global investment and infrastructure.

Given the mounting tensions between Russia and Western governments however, the continued development of the project remains uncertain.

Tonami from the University of Tsukuba said that since the war in Ukraine, Japan and the Arctic community had coordinated on how to respond to the new geopolitical reality, with the seven Arctic states trying to boost their activities in lieu of the Council’s suspended work.

For instance, Tokyo’s newly appointed Arctic ambassador Takewaka Keizo travelled to Alaska earlier this month to participate in the Arctic Encounter, an event hosted by the US and attended by Arctic countries as well as Britain.

The West ‘led’ in creating climate change. Asia can lead the solution

Dodds from the University of London Royal Holloway said Japan and South Korea would seek to work closer with non-Arctic allies such as Britain to cement a Euro-Asian-Arctic arc of cooperation.

Japan has some investment in Russian energy projects, while South Korea is involved with Russian ship building and trans-Arctic shipping plans, he noted.

“Japan-Russian relations over the Kuril Islands/Northern Territories are a possible flashpoint going forward,” Dodds said, referring to the territorial dispute between Tokyo and Moscow.

Last month, Japanese media reported that Russia was conducting drills on islands claimed by Tokyo, days after Moscow halted peace talks with Japan because of its sanctions over its invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s Interfax news agency said Moscow was conducting military drills with over 3,000 troops and hundreds of pieces of army equipment.