Beijing’s South China Sea talks with Asean are worse off than it’s letting on, experts say

- China is confident it will be able to wrap up talks for a code of conduct in the disputed waters, even as the coronavirus has delayed negotiations

- But with recent stand-offs and Southeast Asian states ramping up their claims, an amicable resolution looks farther away than before, analysts say

Why are tensions running high in the South China Sea dispute?

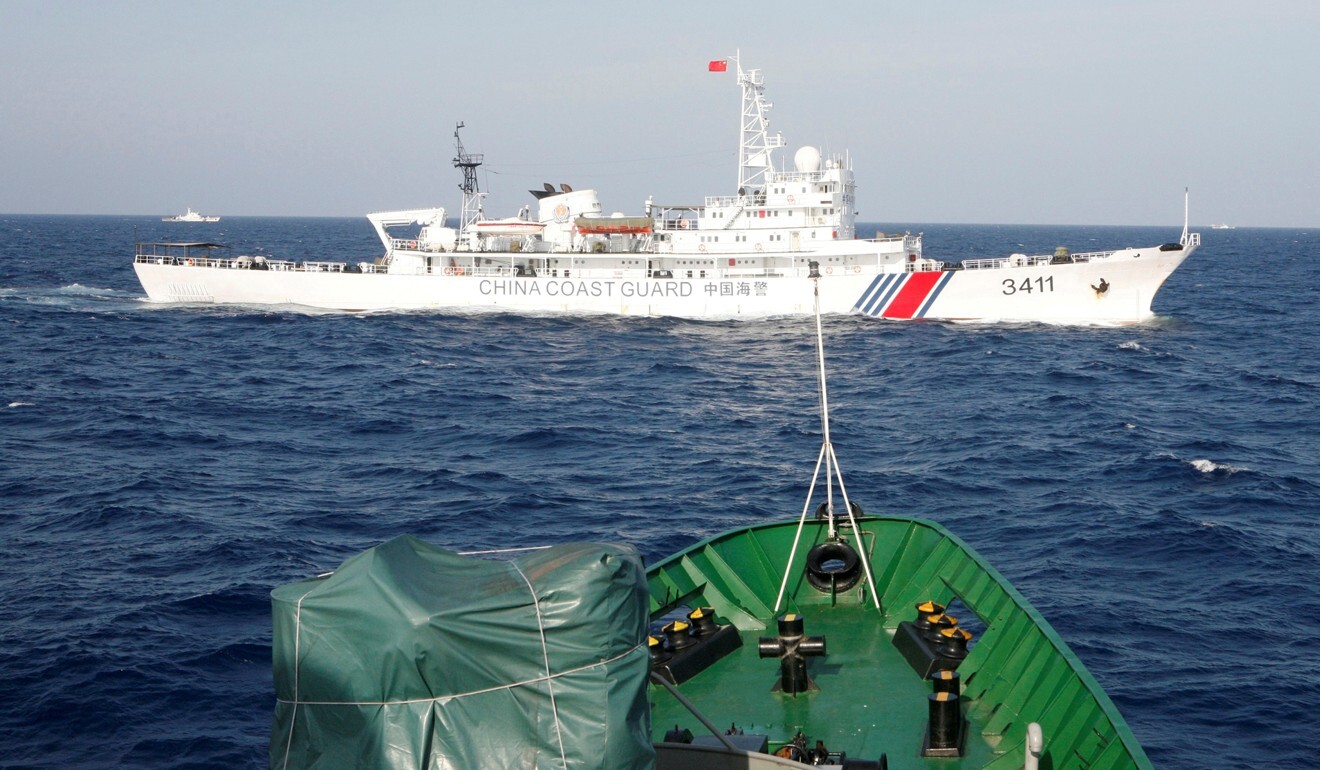

With recent stand-offs in the waters, as well as Southeast Asian claimants ramping up “lawfare” tactics of citing international maritime law to press their respective cases – much to Beijing’s annoyance – an amicable resolution looks farther away than before, the analysts said.

03:23

The South China Sea dispute explained

Hoang Thi Ha, among the six speakers in the discussion organised by Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and the city state’s East Asian Institute, said even without the pandemic, Beijing’s hope to conclude the code of conduct talks by 2021 would still be “an improbable target – ‘aspirational’ as Asean would say”.

On Thursday, China’s embassy in the Philippines issued a statement saying a September 3 virtual working group meeting on the COC was an indication that both sides were “trying to make up for the time lost”.

But Ha, a lead researcher of Asean’s politics and security at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, said that this meeting only saw discussions on “how to resume the negotiations, not the negotiation itself”.

“I think the pandemic has taken away the pretext for China to promote the narrative that all is calm in the South China Sea, and that Asean and China are making progress because there is no substantive discussion to claim progress,” the researcher said.

In South China Sea, Asean states set course for Beijing’s red line

For now, there remained “diametrically opposed positions and interests” between Asean claimants and China on the application of international law – especially the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) – as the basis for maritime claims, Ha said.

“There is this … almost unresolvable issue of the maritime scope of the dispute. So given the recent developments both on the ‘lawfare’ front and tensions at sea, I am not confident that these positions and interests will be reconciled any time soon,” she said.

And if the code is agreed upon, it is likely to be watered down from the versions expected by either sides. Asean wants a legally binding code of conduct guided by Unclos, but China does not want this.

Said Ha: “I think there will be a COC for sure, if there is enough political will from both sides. But it will be settled somewhere around a set of general principles or some mechanisms of incident management.”

Echoing these views was Le Hong Hiep, also from the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, who predicted a delay given how parties such as Vietnam were hoping for a “substantive and effective” accord unlike a 2002 agreement – the precursor to the current talks – that was “totally toothless”.

Asean and China in 2002 signed the non-binding Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, which urged all sides to exercise restraint in the disputed waters.

South China Sea heats up as Indonesia shadows Chinese ship near Natunas

“My prediction is that the negotiations will continue to be delayed, and I don’t think that it will be concluded in the next three years, especially if it is [to be] a substantive and effective COC as Vietnam wishes,” Hiep said.

Julio S. Amador III, a former policy adviser in the Philippines’ foreign ministry, said one hurdle in the talks was a lack of internal meetings within Asean before the bloc’s COC negotiations with China.

“This has been more of an 11-country negotiation because there is no Asean meeting before this Asean-China code of conduct negotiation [so] everyone goes their own way,” said Amador, now the executive director of the Philippine-American Educational Foundation.

The Philippines – currently the designated coordinator of Asean-China affairs – has been the most enthusiastic about the 2021 deadline first set by the Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in 2018.

In its statement on Thursday, Beijing’s embassy in Manila said it appreciated the Philippines’ commitment to the negotiations.

In response, Foreign Minister Teodoro Locsin Jnr, a prolific Twitter user, wrote on the social media platform: “China has my word on that and it will be a COC with which the rest of the world will be totally comfortable, friends and enemies alike.”

He was commenting on a news report on the embassy’s statement.

On Tuesday, Locsin wrote that he had “declared” during last week’s Asean meetings that Manila would “push through to the second draft and get started on the 3rd” before it handed over the mantle of Asean-China coordinator to Myanmar next year.

“That is what I am honour-bound to do,” the foreign minister said.

Also featured in the nearly two-hour virtual discussion was a suggestion by Chinese scholar Li Nan that Beijing could actually benefit if it dropped its nine-dash line claim.

06:24

Explained: the history of China’s territorial disputes

Li, a visiting senior research fellow at the Lion City’s East Asian Institute, said rather than advancing the Asian power’s interests, the line had “complicated Chinese freedom of navigation [and] really generates a lot of conflict with the coastal states of the South China Sea”.

He said China did not need the entirety of the water to preserve its strategic interests, and that giving up the boundary claim – inherited from the Kuomintang government – would in fact benefit Chinese “soft power in relation to the US”.