Between the US and China, new trade roads lead to Afghanistan – and fierce competition

- The Beijing-Washington rivalry has extended to the war-torn country in the dash to build corridors linking Central Asia, South Asia and the Middle East

- Caught in the mix are Iran, India and Pakistan, which are looking to balance their own ties to the great powers with the need for regional connectivity

What China has to fear from a US-Taliban peace deal in Afghanistan

Analysts and experts tell This Week in Asia that the vast overlapping area of West Asia is reverberating from the impact of growing diplomatic hostilities between China and the US.

Recent diplomatic activity in South and Central Asia has highlighted the clashing connectivity agendas of China and the US.

The American diplomatic campaign to promote its interests in the region, at the expense of China’s belt and road plan, was given renewed momentum in early July by Zalmay Khalilzad, the US special representative to Afghanistan.

Touring the region, he was accompanied for the first time by Adam Boehler, chief executive of the US International Development Finance Corporation, which represents an alternative source of project financing to the belt and road strategy – which Washington characterises as a “debt trap”, much to Beijing’s annoyance.

In a series of meetings with the foreign ministers of Pakistan, Afghanistan and the five Central Asian republics – as well as Taliban negotiators based in Qatar – Khalilzad and Boehler sought to reinforce the message that Washington intends to remain the top geopolitical player in Afghanistan, on the basis of its continuing role as the country’s major financier.

China-India border dispute: is Pakistan about to enter the fray?

China’s ambassadors to Afghanistan and Pakistan had previously described this as “a dream project” for Beijing, because it would interconnect two major belt and road routes.

Following an agreement struck recently, China is undertaking a US$7.2 billion rehabilitation of Pakistan’s rickety railway network.

In Tashkent, Khalilzad also pushed energy export projects, notably the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) natural gas pipeline project.

Turkmenistan is China’s single largest source of natural gas, accounting for 27 per cent of all imports last year. Beijing has expressed an interest in joining TAPI, but Washington – which began pursuing the project in the 1990s – has not acquiesced.

02:29

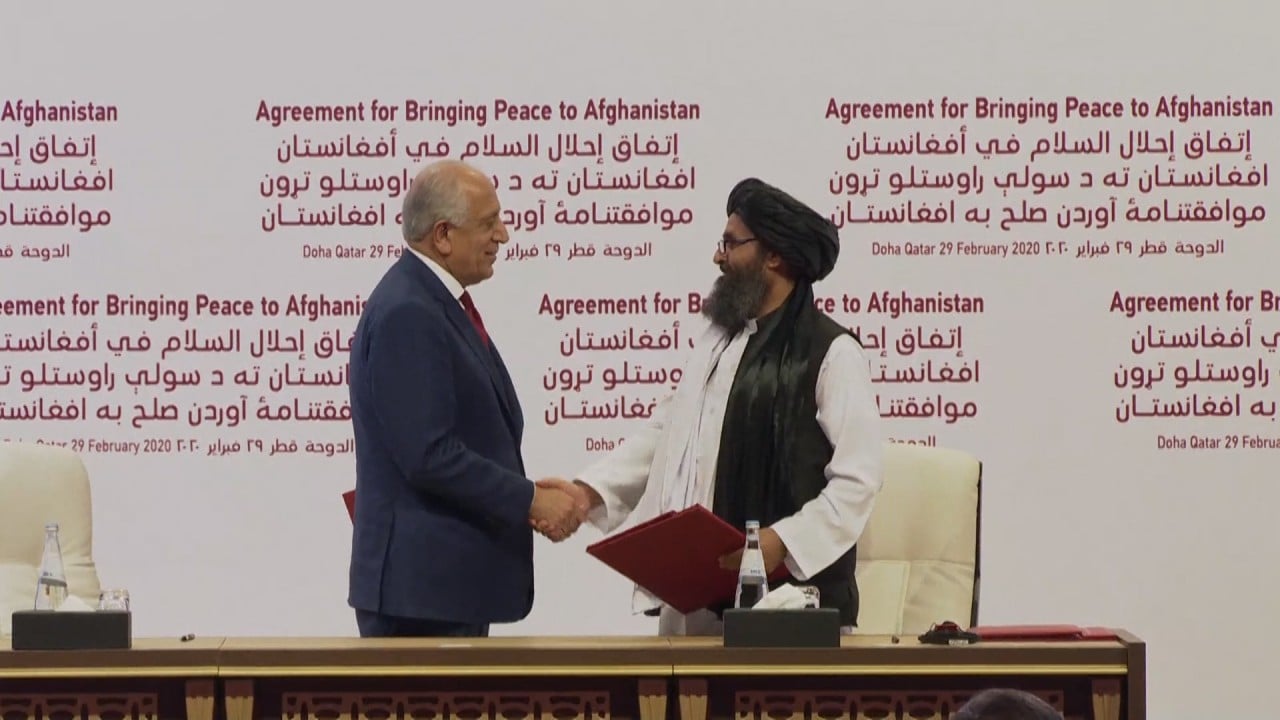

US, Taliban sign historic peace deal to end war in Afghanistan and withdraw US troops

‘NO ISSUE CAN REMAIN UNAFFECTED’

Meanwhile, China has been working hard to deepen cooperation with all belt and road partner governments in South and Central Asia and the Middle East, through joint efforts to counter the Covid-19 pandemic. India is the notable exception.

In a rare four-way video conference on July 27 with the foreign ministers of Nepal and Afghanistan and Pakistan’s development minister, China’s foreign minister Wang Yi proposed expanding their pandemic cooperation to establish a “green corridor” between them.

China will sound willing in principle to extend the CPEC to Afghanistan but it is cautious in practice

He also pressed for the development of a multimodal trans-Himalayan corridor and the extension of the CPEC into Afghanistan.

The trans-Himalayan corridor would integrate Nepal into the belt and road plan via Tibet, Xinjiang and Gwadar – reducing India’s historic stranglehold over landlocked Nepal.

Beijing’s recent endorsement of Islamabad’s proposal to extend the CPEC into Afghanistan further diminishes India’s prospects of expanding its footprint there.

However, Andrew Small, a senior transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States think tank, said he still expected China to pursue belt and road ambitions in Afghanistan with caution.

Afghanistan remembers Japan’s Tetsu Nakamura, the slain doctor who brought water to thousands

Islamabad also came under pressure from US special representative Khalilzad in early July to scale back the CPEC and cooperate with American connectivity plans for the region, which would require Pakistan to work with perennial enemy India.

The nuclear-armed South Asian adversaries have ceased diplomatic contact since last August after India unilaterally revoked the semi-autonomous status of the part of Kashmir it administers.

Its decision prompted China to raise the issue at the United Nations Security Council for the first time, albeit on Pakistan’s request, setting into motion an escalation of tensions with India that later boiled over in Ladakh.

However, Pakistan moved quickly to reassure China that it had no intention of wilting under US pressure.

The day after Khalilzad’s talks in Islamabad, Pakistan’s foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi spoke with his Chinese counterpart Wang by telephone. The following day, Prime Minister Imran Khan declared the CPEC would be completed “at all costs”.

Soon after, Islamabad moved to placate Kabul by lifting a short-term suspension of Afghan transit trade to India, imposed in March as Covid-19 spread throughout the region. It has also recently reopened all its border crossings with Afghanistan, facilitating the first transit container and bulk cargo consignments from Gwadar.

The real reason China wants peace in Afghanistan

Instead, the World Bank is funding the new motorway from the Pakistani city of Peshawar via the storied Khyber Pass to Torkham in Afghanistan as a build-operate-transfer (BOT) project. From Torkham, it would connect to Kabul via Jalalabad in the country’s east.

Within Pakistan, the upgrade of the road from Chaman to the port city of Karachi – where Hong Kong’s Hutchison Ports operates container terminals – has also been recently tendered as a BOT project.

Chaman is connected by road to the strategic southern Afghan city of Kandahar. Chaman is close to Quetta, the administrative headquarters of Balochistan province, where Gwadar port is located.

Instead, Pakistan has apparently decided to limit China’s role in regional connectivity to motorways dedicated to connecting Gwadar to Xinjiang.

CONNECTIVITY COMPETITION

But with tensions between Beijing and Washington reaching fever pitch, Pakistan’s apparent attempt to balance its ties with the US may not have been well received by its “iron brother” as it used to be.

“Pakistan has been feeling under greater pressure from the Sino-US rivalry,” said Small, the German Marshall Fund scholar.

He said China had normally seen good US-Pakistan ties as advantageous, given that it meant Islamabad could then benefit from US economic and military support – making it a more effective balance to India in the region.

Similarly, the US until recently had also seen China’s economic activities in Pakistan, including the CPEC, as potentially beneficial – and indeed, actively encouraged Beijing to expand its investments there, Small said.

“This has changed on both fronts – the US now sees the CPEC more through the wider prism of competition with China over the Belt and Road Initiative, and China has treated Pakistan’s efforts over the last year to fix relations with Washington more coolly than has traditionally been the case,” said Small, who is also author of The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics. “Pakistan will continue to try to straddle this, but it’s not as easy as it used to be.”

Islamabad is also watching the ongoing negotiations between Beijing and Tehran with great interest.

“Developments such as closer China-Iran relations that promote regional stability, economic development as well as connectivity will be welcomed by Pakistan,” said Lodhi, the former ambassador. “As China’s strategic partner, Pakistan respects Beijing’s move for closer ties with our neighbour Iran and desire for greater economic connectivity in our region. We await details of whether Pakistan has a role to play in this regard.”

A recently leaked draft of the proposed 25-year strategic deal envisions the export of Iranian natural gas and electricity to Gwadar port and the rest of Pakistan.

Seyed Mohammad Marandi, a professor of English literature and oriental studies at the University of Tehran, said it was “natural” that China and Iran would seek closer ties because they had enjoyed a conflict-free relationship based on Silk Route trade and civilisational exchanges for several millennia.

“This creates a natural convergence between nations to protect themselves against a great menace, the US,” Marandi said. “China and Iran, as two powerful independent countries, have an interest in creating relationships that can be productive for their peoples, but also that can contain a menace coming from a third party.”

India, Asia’s third-largest economy after China and Japan, stands to lose out because of the strategic agreement between Tehran and Beijing, which is expected to be concluded by March next year.

Iran has grown weary of India’s go-slow over infrastructure it was meant to fund at Chabahar port, and is increasingly perturbed by New Delhi’s shift away from its historic non-aligned Cold War position towards a diplomatic and security alliance with the US.

A deadly turn on China’s Belt and Road raises the stakes in Pakistan

Iran has also been highly critical of Indian repression of the Muslim-majority population of Kashmir since August last year.

“The Iranians have become less impressed with the behaviour of India, especially because the Indians have not really invested in the Chabahar project,” Marandi said. “If the Indians simply want to keep the project and do nothing, they are going to lose it.”

China is the probable alternative partner, but “you can be sure the US will go after any significant China-Iran connectivity tie-ups,” Small said.

“Given that Iran is subjected to the full array of sanctions from the US Treasury, it makes it practically very difficult for firms and individuals to transact with Iran without dire repercussions for their status in the international financial system.

“This has already had a substantially inhibiting effect on China’s economic relationship with Iran. So for now, although some of these projects can be envisaged and planned, the execution will be significantly affected by these wider dynamics.” ■