As China-India tensions escalate, can Sri Lanka avoid becoming a pawn in a big power game?

- New Delhi’s historical influence over Colombo looks to be waning in the face of increased investment and other economic overtures from Beijing

- But observers caution the South Asian island nation would be better off looking to Singapore’s example and avoid picking sides

In June, Indian media reported that Delhi had yet to make a decision on Sri Lanka’s request – made four months before – for a postponement of the US$960 million debt it owes, as well as for a US$1.1 billion special swap facility to boost the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Can Sri Lanka’s neutral foreign policy steer it clear of US-China tussles?

Earlier this month, the Sri Lankan government cancelled a Japanese-funded light railway project in Colombo, while insisting it would not accept a US$480 million grant from independent US foreign aid agency Millennium Challenge Corporation.

“We shouldn’t be too close to India because China is the only country that can provide us with funding. India has no money to offer,” he said.

“Our challenge will be to maintain an engagement that doesn’t offend either [India or China].”

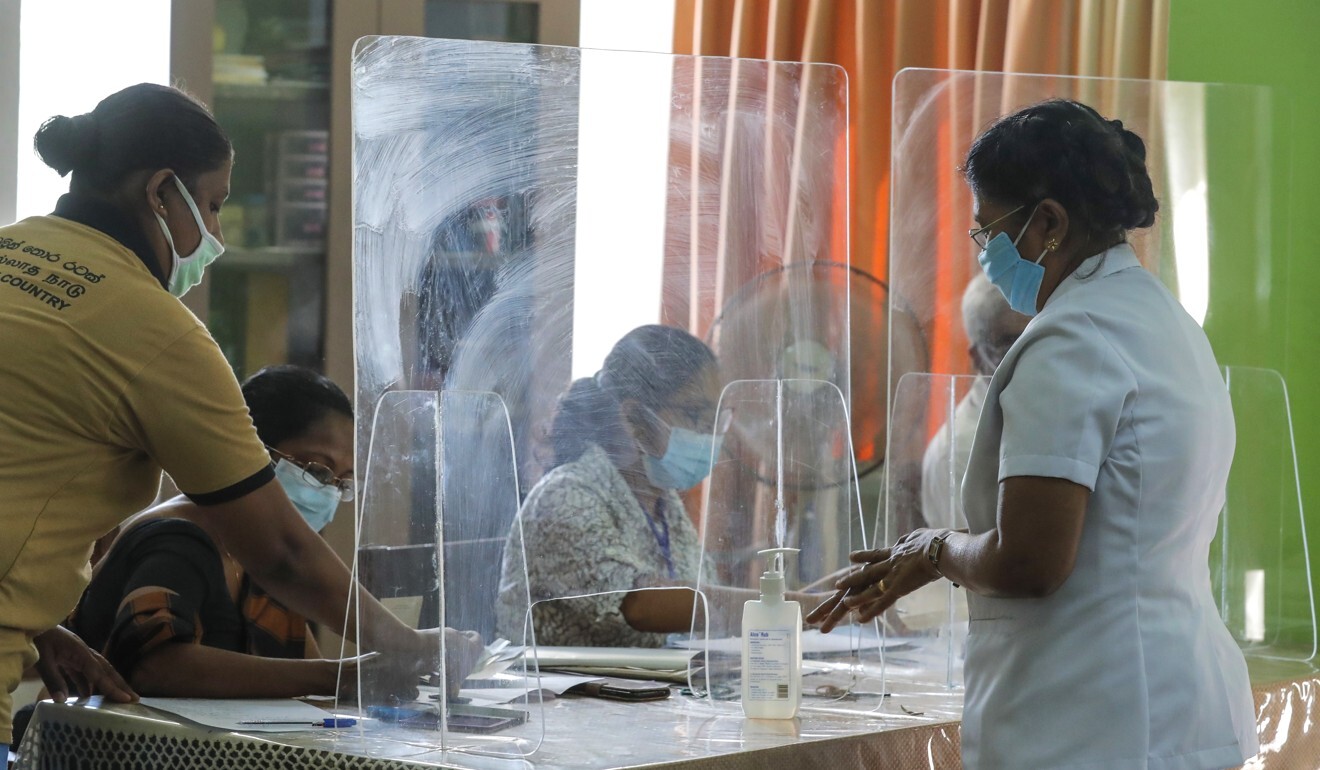

The real test will come when Sri Lanka elects its new government after the general election in August, said Shakthi de Silva, a research assistant with the Lakshman Kadirgarmar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies in Colombo.

Rajapaksa’s party – widely seen to be pro-China but currently pledging a strict non-aligned policy, and led by his brother the charismatic Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa – is widely tipped to win, particularly given the positive perceptions surrounding the president’s handling of the coronavirus crisis.

It’s like during the Cold War, [when] we were auctioning the US and the Soviet Union off against each other

Parties fighting the election will be eager to promise voters all types of initiatives and projects, using funds that can only come from either India and China – and there is a chance that both sides would want to offer such financial overtures.

“It’s like during the Cold War, [when] we were auctioning the US and the Soviet Union off against each other,” said Dr Susantha Goonatilake, a Colombo-based scholar and former president of the Royal Asiatic Society.

China-India border dispute may force South Asian neighbours to pick a side

“We got various industrial plants from the Eastern bloc, the West gave various things and so on. But it’s advisable that we maintain a positive neutrality between China and India these days.”

The business community is also concerned about Sri Lanka taking sides, saying it could result in economic repercussions.

“We should be neutral, and should not even talk about benefits we may get from either country in this situation,” said Kosala Wickramanayaka, president of the Colombo-based International Business Council.

Goonatilake said Chinese assistance to Sri Lanka would surely wane if Colombo was seen as supporting India in the current border dispute, while Delhi has similarly always found ways of sending Colombo messages about remaining neutral.

He pointed to how Indian navy commanders who were present at recent defence dialogues in Sri Lanka had made what he described as “belligerent statements”, telling Sri Lanka in effect to “watch what it is doing with China”.

“Unless we are aware of how big countries exercise power, Sri Lanka cannot survive. We have to be aware of how large and small countries are dealing with each other,” he said.

“We in Sri Lanka need to be analysing the plots others are making with reference to us, or in the region. That’s the way we can benefit from relations with both countries.”