Will Thailand’s election turmoil hit China-backed US$54 billion Eastern Economic Corridor?

- Princess Ubolratana Rajakanya’s abortive prime ministerial bid may have stunned investors

- But the Thai baht and the kingdom’s economy have a ‘Teflon’ reputation

Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor, a 1.7 trillion baht (US$54.2 billion) development heavily reliant on Chinese backing, should emerge unscathed by the kingdom’s pre-election political turmoil, analysts say.

In any other Southeast Asian economy, the political risks emanating from that episode alone would have triggered a major crisis in investor confidence.

But keen observers of Thailand say the “Teflon nature” of the kingdom’s economy and the Thai baht, largely resilient to internal shocks, is likely to continue.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi holds talks in Thailand ahead of general election

The baht has shown its mettle with a standout performance in 2018 even as the currencies of emerging economies like Indonesia were routed – something likely to be welcomed by investors in the corridor, or EEC.

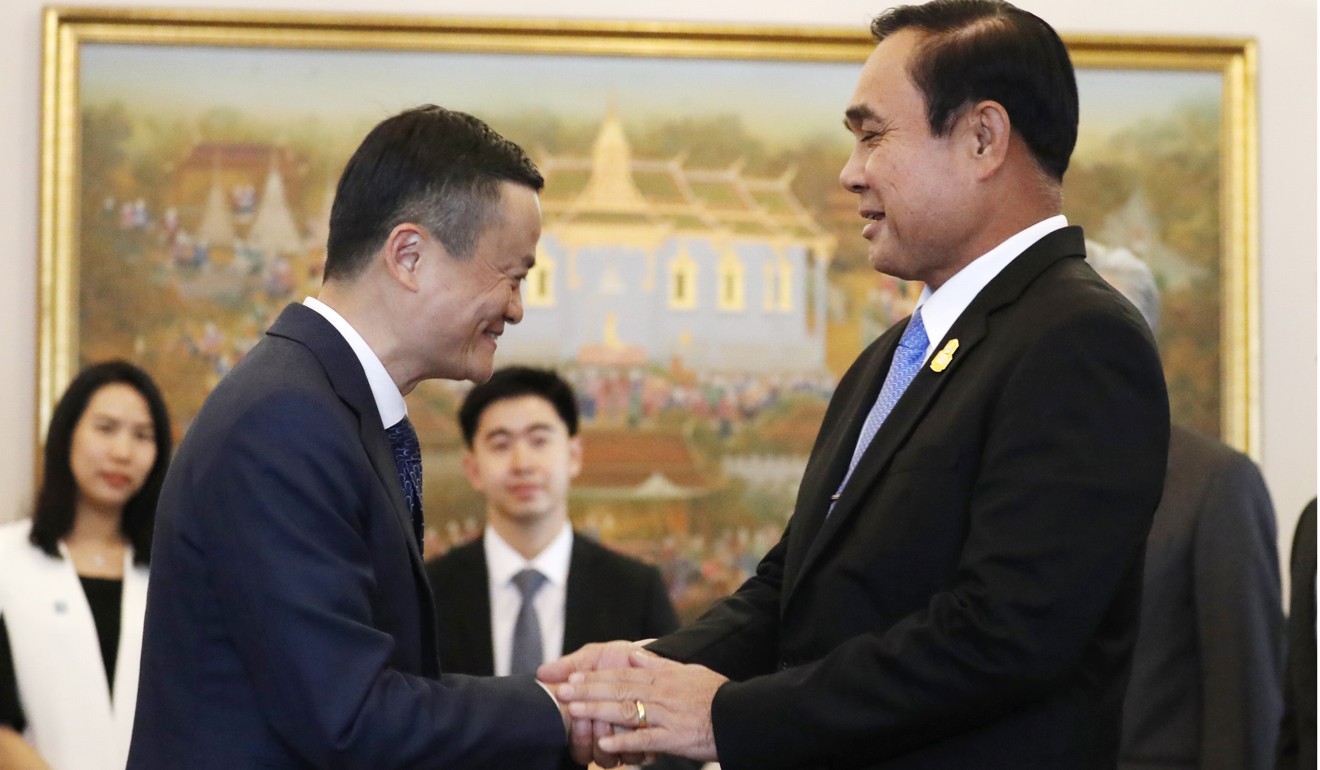

The mega project is the brainchild of the military administration that seized power from a Shinawatra government in 2014, and has been built by the junta leader Prayuth Chan-Ocha as the cornerstone of plans to transform the country into fully developed status.

It seeks to replicate an investment programme from the 1980s, also called the Eastern Economic Corridor, that is partly credited with making the country the world’s fastest growing economy from 1985 to 1994.

The EEC covers an area greater than 13,000 square km – more than six times the size of Shenzhen – and its development is enshrined under a 20-year economic plan devised by the junta that future governments are obliged to adhere to.

The zone spans three coastal provinces, with the tourist hub of Pattaya at its heart.

Piti Srisangnam, a professor of international economics and finance at Chulalongkorn University, said the election – in doubt for months after repeated delays – was an upside factor for investments.

“Politics is one factor, but at least the upcoming election is a good signal because there’s a clear time frame of what to expect,” Piti said.

Even before last week’s developments, top officials overseeing the EEC emphasised how the project was insulated from political turmoil, which has become a norm in Thailand over the last two decades.

Kobsak Pootrakul, a former top junta official who is now part of a pro-military party contesting the elections, told This Week in Asia that careful plans had been laid to ensure investors’ interests were protected whichever way the polls went. His Palang Pracharat party, which has picked Prayuth as its preferred prime ministerial candidate, is viewed as the favourite because of election rules seen as stacked against the Shinawatra bloc.

Shinawatra proxies set their sights on Thailand’s economy after failed bid to enlist Princess Ubolratana

Kobsak said that by the time the new government was in place – expected to be some time in May – about “five or six projects” in the EEC would be underway.

“These main projects will attract investors and change the landscape,” he said.

Among five key infrastructure projects that have been given the green light are the development of two seaports, an “aviation city” in the town of U-tapao, and another aviation maintenance, repair and overhaul hub being spearheaded by Thai Airways.

Self driving cars and robots are reportedly part of the endeavour, which comes even as the Chinese firm faces an onslaught of bans and restrictions in the west.

Last year it said it would spend US$350 million to build a distribution hub in the EEC.

Kanit Sangsubhan, an economist appointed as the EEC’s secretary general, is another official who has sought to shore up investor confidence ahead of the coming election.

Speaking to Thai business reporters in January, he outlined how the EEC was enshrined in law – the EEC Act enacted by the junta came into effect last May – which in turn means any post-election government cannot unwind the project.

“Thailand will benefit from the Belt and Road Initiative. It will see more money pouring in, some related to the EEC, some not,” he said. One direct impact of the EEC’s initial upgrade of a port in Laem Chabang, the professor said, would be greater trade with China’s Guanxi region.

From Pattaya with love: forget sex trainers, meet the real Russians of Thailand’s sin city

Kanit acknowledged as much in a Bloomberg interview last year.

“Japan and Europe have been the major players for more than 30 years,” he said, adding that “Chinese investors can play a bigger role in EEC development in the future. The EEC will be a balancing ground for investment.”

Kevin Hewison, a long-time observer of Thai politics, suggested there was another key reason why Chinese investors need not be too concerned about getting burned if the EEC goes south: mainland investment in the zone may not be that high.

“Despite a lot of highly publicised deals with China under the junta, little has materialised,” he said.

A US$7 billion high-speed rail link connecting Bangkok to Nong Khai – the border with Laos – remains in limbo years after it was first proposed.

The link was envisioned by China as a seamless land route connecting Kunming to Bangkok via landlocked Laos.

“The high-speed railway is one example: lots of talk and hot air, but little result,” Hewison said.

“Actual Chinese investment, while increasing, remains low …[but] there’s been plenty of junta attention to Japan as investors, which makes sense as Japan remains the largest investor [in Thailand].” ■