Facebook, WhatsApp target fake news for Asia’s election season, but is it too little, too late?

- The social media giant has election teams working in Australia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand

- But with near to a billion people in the region posting every month, some say the genie is already out of the bottle

“We have teams working to prevent election interference on our services. This includes detecting and removing fake accounts, limiting the spread of misinformation, tackling coordinated abuse, preventing foreign interference, and bringing more transparency and accountability to advertisers,” Harbath told the South China Morning Post on Tuesday from Bangkok. “We have made big investments to make sure we are prepared to handle whatever might happen.”

Maria Ressa, a Filipino journalist and founder of the Rappler news website, is among those who are waiting to see if Facebook is truly committed to cleaning up the frenzied content unleashed by the 917 million people who use the platform each month in the Asia-Pacific, including 394 million in Southeast Asia. Ressa was named as one of Time magazine’s Persons of the Year 2018, as one of the journalists fighting a global “War on Truth”.

“Will Facebook take on the fundamental responsibility of gatekeeper, now that it is the world’s biggest distributor of news? Think about it: when journalists were the creators and distributors of news, we took that role seriously. At least you had the facts, and that’s what protected democracy,” said Ressa, whose Rappler team collaborates on fact-checking with Facebook in the Philippines. “When tech took over, they shied away from that responsibility. They let lies spread faster than truth. In the real world that’s a crime, in the virtual world that’s impunity.”

In Ressa’s view, the human journalists who were once the so-called gatekeepers have been replaced by “at best content moderators who have no cultural context of the material that they’re being given seconds to evaluate”.

NUANCE AND CONTEXT

Since 2016, Facebook has worked to make its election monitoring in Asia more localised, Harbath said. The company now has third-party fact checkers in India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Pakistan and has run anti-disinformation programmes in those countries, as well as in Thailand and Singapore.

“We now have teams that understand the nuances of the election and the context of the region. I’m in Thailand and our team here speaks Thai and understands the culture,” she said.” We’ve also invested heavily in digital literacy to make sure that we are helping people understand what they’re seeing online.”

Facebook is bent on friending China, but …

Harbath said a portion of Facebook’s 30,000 content security personnel – up from 10,000 in 2017 – were watching Asia, and that percentage would increase during election times. Facebook has faced criticism in Asia over recent elections in which governments and politicians used the platform to promote fake news, smear campaigns and propaganda.

At the moment, Facebook faces what could be a record fine in the US for privacy violations related to the case of data mining firm Cambridge Analytica, which hijacked the personal data of as many as 87 million Facebook users without their knowledge.

Harbath conceded that Facebook had faced an intense 12 months, but said it had ended the year “with much more sophisticated approaches than it began”.

“We want to protect these elections and make sure people have a voice. We take that responsibility very seriously,” Harbath said. “We learn from every election we work on – and not everything works. Bad actors continue to circumvent our systems.”

Why Facebook faces the MySpace graveyard in Asia

Claire Wardle, the co-founder of First Draft, a US-based non-profit organisation that studies disinformation, was also doubtful. She said the problem in monitoring Asian elections was scale.

“The bottom line on elections anywhere is that it’s very difficult in real time to identify threats, and whether they are real or foreign or domestic. The challenge in Asia is that social media use is so much higher and there are language difficulties,” Wardle said on Tuesday. “Even in the US, where Silicon Valley is based, we’re still arguing about Russian interference in the 2016 election.”

She continued, “I’m glad Facebook is taking these elections in Asia seriously, but I just don’t see that any of the platforms are geared up to monitor this in real time and take down content effectively.”

‘HORRIFIED BY VIOLENCE’

The messaging service WhatsApp on Monday made its own move to thwart hoaxes and fake news – by blocking any message worldwide from being forwarded to more than five individuals or groups. Carl Woog, a spokesman for WhatsApp, said that five was chosen as the limit because “we thought that was the appropriate number for forwarding to close friends and family while preventing abuse”.

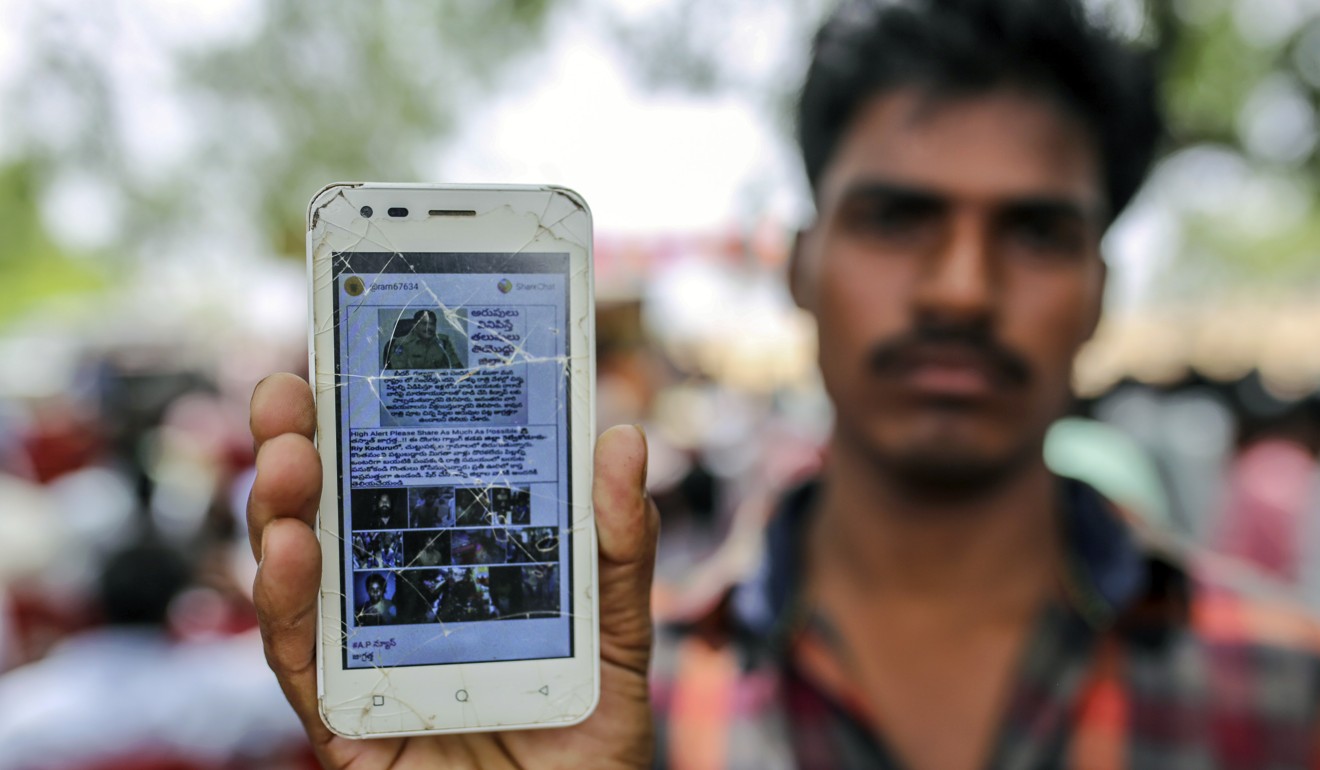

The move by WhatsApp, which has 1.5 billion global users, came after a six-month study in India after a wave of mob killings was blamed on rumours circulated by the app. In Indonesia, where it is used by more than 40 per cent of the online population, WhatsApp has been accused of spreading misinformation about, among other things, child kidnappings and a vaccination campaign.

Experts have pointed out that the app’s end-to-end encryption allows groups to exchange texts, photos and video without fact checkers or the oversight of the platform.

“We were horrified by the violence in India,” said Woog. “We have concerns about the spread of viral misinformation in the communities where WhatsApp has an important role. We’ve made important product changes that will be in place in time for elections in India and Indonesia.”

Woog said the changes included a change in the message-forwarding process that “encourages the user to think before sharing” and public awareness campaigns on radio, TV and online ahead of the elections. WhatsApp was bought by Facebook in 2014 for more than US$19 billion.

Budi Irawanto, a visiting fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore who is conducting a study on social media in Indonesia, welcomed the move by WhatsApp, saying that it may encourage users to rethink what they share.

“In the Indonesian context, there is no guarantee that users will not share fake news or hoaxes unless they constantly double-check all news that appears on their feed against facts or the reliability of the source,” Irawanto said. He said Indonesia’s social media users tended to select news that affirmed their beliefs and values, rather than take on alternative news or viewpoints.

“It should also be noted that WhatsApp is rather effective in raising awareness for people affected by natural disasters in Indonesia. So, the limit imposed by WhatsApp may not serve to be helpful in responding to these emergencies.”

‘ALL POWERFUL’

Harbath, who joined Facebook eight years ago, said the company’s Asian build-up started after polls in Australia in 2013.

“I’ve focused on this region for many years, and the team has continued to grow as we work to protect elections on the platform,” she said. “The DNA of our company has changed. Facebook has to continue to get better – that’s our new normal.”

Three of Facebook’s main content policies were influenced by recent events in Asia. Its new policy to remove misinformation that could lead to “offline harm” was introduced last year after sectarian violence in Myanmar, and an update to its “credible violence” policy about the risks faced by certain groups, including journalists, was also drawn from Asia.

Why Facebook and Google’s China dream will cost more than it pays

An update of Facebook’s hate speech policy was based on the abuse “on and off the platform” in India. Facebook wrote, “We updated our policy to add ‘caste’ to our list of protected characteristics, and we now remove any attack against an individual or group based on their caste’.”

Yet Sophal Ear, a professor at Occidental College in California, said that in some smaller Southeast Asia countries “Facebook is all powerful.” He said everyone in Cambodia who uses Facebook, uses it for news. “Doesn’t Facebook understand its outsize influence in a small place like Cambodia – where it is the lifeblood of information in an increasingly closed society?”

Ear also questions Facebook’s willingness to accept advertising payments from authoritarian leaders like Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia.

Ressa, the Rappler chief, is even more direct: “The people who created Facebook, the people saying that they want to protect free speech have never been in parts of the world where you cannot speak because you’re afraid. In the global south, people can die for what they say.”

But Ressa, who has suffered harassment campaigns on Facebook, isn’t ready to give up.

“I am really critical because I have felt the misuse personally. But I am seeing them fix it, and I am helping them fix it, because what they have created is incredibly powerful,” she said. “Facebook is a huge, growing organisation that is still learning. We’re dealing with some really smart people – and they have been put on notice.”

Harbath agreed that Facebook faces hard decisions as it tries to balance free speech with safeguarding democracy.

“Our mission is to connect the world, level the playing field and give more people a voice,” Facebook’s Harbath said. “What we have learned over the past couple of years, is that when you do this you are bringing out all the good – and bad – of humanity. We want to amplify the good and mitigate the bad, but it’s been a process.

“We are not the same company that we were in 2016. We’re not even the same company we were at the beginning of last year – and what we have learned in Asia is part of this growth.”

“BOLD ACTION AGAINST BAD ACTORS”

Edited excerpts of an interview with Katie Harbath, director of global politics and government outreach at Facebook

How can Facebook stop people from using the social network to whip up lynch mobs and hate speech, as has happened in Sri Lanka and Myanmar?

We have a responsibility to fight abuse on Facebook. This is especially true in countries like Myanmar where many people are using the internet for the first time, and social media can be used to spread hate and fuel tension on the ground. It’s why we created a dedicated team across product, engineering and policy to work on these issues. This team has introduced policies to address the spread of misinformation leading to offline harm, improved our technology to better detect bad content, taken bold action against bad actors that violate our policies, as well as those who have committed or enabled serious human rights abuses, and worked with local partners to deliver digital literacy and education programmes.

Last week, you announced you’ll be rolling out additional political advertising protections ahead of upcoming elections in Asia. What are your plans for this region?

We want to prevent foreign interference in elections and give people more information about the political ads they see on Facebook and Instagram. This transparency sheds new light and holds advertisers and us more accountable. We took steps to address this globally for all ads last year – even those not targeted to you, and created additional tools for political ads in the United States, Brazil and Britain. That said, each country is unique and we want to gather feedback and consider local laws as we look to bring these tools to more places in 2019. We’re committed to continuing to help protect elections into 2019.

What’s going to be different about Facebook’s approach to elections in Asia this year?

There are four main areas we are working on. They are combating foreign interference, detecting and removing fake accounts, increasing ad transparency, and reducing the spread of false news. We have deployed this approach in elections around the world, including the Asia-Pacific. We have invested in new technology and more people … last year we broadened our policies against voter suppression – action that is designed to deter or prevent people from voting. And we took tough action against coordinated inauthentic behaviour. Actions in this region include the removal of coordinated inauthentic behaviour on our platform in Bangladesh, which our investigation indicated was linked to individuals associated with the Bangladesh government, in the run up to its elections. We also took down a spam network in the Philippines and earlier this month we banned a digital marketing group in the Philippines for coordinated inauthentic activity.

What policies and personnel are in place to handle this shift in non-English-speaking communities?

We have dedicated teams working on all upcoming elections in the Asia-Pacific. This includes local language experts and people who understand local context. These teams help inform our policy, product and partnerships work on elections in this region. We also work with 12 third party fact-checking organisations across the region, including in the Philippines, India, Indonesia and Pakistan.