Chinese cash, American muscle, and Marawi’s discontents

Outsiders jostle for space in war-ravaged Philippine city while its own languish on the margins waiting for the government to rebuild it anew

But that means little to the Usmans, trapped in an evacuation camp with little prospect of making it back to their home as they knew it, in a city laid to waste. A year after the conflict erupted, the family is among the 237,000 people – or 67 per cent of the city’s population of 353,000 – who remain displaced. Those who managed to salvage sufficient resources before fleeing found places to rent elsewhere. Others moved in with relatives or friends in nearby towns and villages. But for the likes of Usman, a tricycle driver with neither the resources nor resourceful acquaintances, a yellow tarpaulin tent it is, with no electricity and limited water, on the outskirts of the nearby city of Iligan.

I don’t get to meet Usman the couple of times I visit the encampment, one of the many scattered around Marawi. “He’s working as a carpenter, trying to save up and fix the tricycle. It’s all we have left,” says his wife Faida Mamayandig at the camp’s community area, which is slowly coming to life in what would otherwise be a dull afternoon. The inhabitants are gathering around as the military is about to start a “psychosocial intervention” session to help ease their trauma.

It’s a unique project, with seven female soldiers in hijab armed with two stereo speakers engaging with the camp’s children in an hour-long song and dance session. They perform musical renditions of Islamic prayers, children’s poems and even YouTube star Sophia Grace’s Girl in the mirror, with periodic exhortations of “sempre peace!”

“We are trying to show them that we are one of them, not enemies, as they have been taught by IS. They used to live in an environment of violence, fear and hatred. Now they want to draw, study and go to college. They now trust the military,” says Second Lieutenant Angel Manglapus, leader of this most extraordinary girl band.

Watch: A year after siege, Philippines’ Marawi lies in ruins

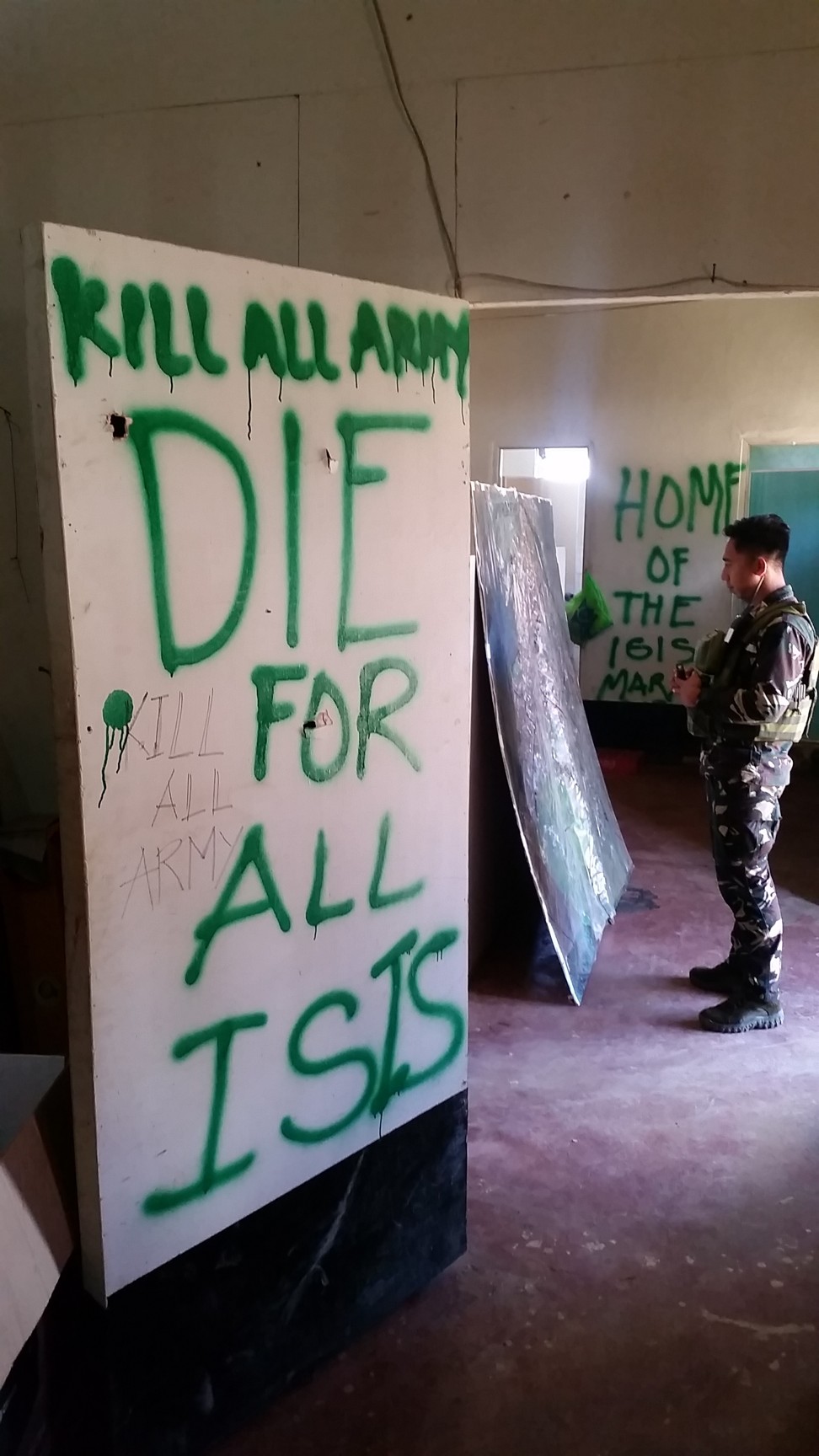

Going by the children’s response, she’s doing a magnificent job. But the wounds of Marawi are too raw and run too deep. If jihadi group Abu Sayyaf’s leader Isnilon Hapilon, the supposed “emir” of IS in the Philippines, and the city’s infamous Maute brothers, whose frenzied band led the siege and mayhem, were aiming to establish an Islamic caliphate here, they were partly successful. The flattened markets, collapsed homes, pockmarked mosques and the twisted beams of shelled concrete buildings have reduced what was once southern Philippines’ liveliest trading hubs to a dead ringer for war-ravaged Middle Eastern ghost towns in late-night news. The “ground zero” in the eastern part of the city, the most affected part of Marawi where the Maute had finally dug in, could very well be Mosul.

So “sempre peace” is still a way off. Right now, there is just too much that Marawi’s uprooted still do not understand about the war to talk forever peace: how exactly did the war start, why can’t they go home now that it’s over, why did the city have to be razed and why must it be built afresh, who took their belongings, and how many civilians and terrorists died.

“There can be no healing without knowing the number of people killed in the siege,” says Hamidullah Atar, Sultan of Marawi, pointing to the inconsistency in the official figures of the number of militants. “Not long ago they were saying there were an estimated 250 Maute fighters, now one hears 920 terrorists were killed. We believe many of these are civilians.”

The military has said it may have underestimated the strength of the jihadis, which was also the reason the war drew out longer than initially estimated. As the Sultan himself says, he was taken aback by the number of local youngsters he found wielding a gun during the siege – people he thought he knew well but had no idea they had been radicalised.

There is also lack of clarity in the exact sequence of events that led to the crisis or how it escalated. Muslim groups are calling for a full inquiry but Congress doesn’t seem interested, says Carlos Conde, the Philippine researcher for the Asia division of Human Rights Watch.

Citing similar past campaigns, he says there is never a full accounting of the damage to civilian lives and property when it comes to conflicts involving the Muslim south in the Christian-majority country. “These battles are couched in a language of terror and secession. So the indifference may be a combination of discrimination and military nationalism.”

“If they don’t care about us Muslims, they should at least do an inquiry for the sake of the soldiers who died,” says Drieza Lininding, chairman of the Moro Consensus Group, a civil society organisation.

The government has said more than 1,000 people died in the war, including 165 soldiers and policemen. But exact figures may be difficult yet as skeletons are still being found in the debris.

On a stopover at a public burial ground, I find 36-year-old Estella Valesco arguing with local health officials to take possession of the body of her father Puerto Noto, who died in the bombings. She wants to give him a proper burial, but is told the remains must first be sent to Manila for a DNA test.

In war situations, where body parts can be severed from the impact of explosives and mix with the remains of other victims, or animals, only DNA tests can properly establish identity. But Valesco wants the body now, she wants closure. The health workers prevail, Puerto Noto disappears into a storage room in a blue bag, and Valesco leaves the burial ground in tears.

Ticking bombs

Captain Larry Camacam of the 53rd Engineer Brigade escorting me at “ground zero” warns about unexploded bombs hidden in the debris every time we get off the car, presumably to keep me from wandering off into crumbling buildings. It’s working, and I mostly keep to the road, which is lined with billboards with pictures of unexploded ordnance, or UXO.

These are part of a campaign to raise awareness about undetonated explosives. According to Rudy Lumapinet, a community liaison and mine risk education officer at the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action, his organisation has in the past year held nearly 500 workshops with displaced groups and relief workers to help them recognise and tackle UXOs and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

“As of the end of January, the forces have cleared 753 UXOs and 76 IEDs. Search is on for eight big UXOs that were airdropped,” he says. “There can still be other undetected medium-sized UXOs and IEDs.”

The government says UXOs are the main reason for not allowing residents back into the most affected areas. After it clears the UXOs and all the debris, it wants to rebuild the city from ground up. Only then will its inhabitants get to return.

We didn’t have much, we lost it all: Marawi to Tent City, one refugee family’s story

Five Chinese contractors led by China State Construction Engineering Corporation are in the running for the reconstruction project estimated to be worth upwards of US$1.5 billion. Duterte has said Chinese leader Xi Jinping gave him a US$79.5 million grant to help rebuild Marawi after a meeting in Beijing last month.

With their Filipino partners, the Chinese firms form the consortium that has submitted an unsolicited offer as the “original proponent”. A “Swiss challenge”, which allows other developers to match their offer, will be held for the final award, most likely by next month.

“We’ll make Marawi a better place. It’ll be a modern metro. Calamities lead to new opportunities, a new Marawi will emerge from the ashes,” Secretary Jesus Dureza, the presidential adviser on the peace process to end the long-running southern insurgency, tells me at his office in Manila. The government does not have a clear timeline yet, he says, it may take two to three years.

Back in Marawi, those displaced by the war do not understand why they can’t go back right away. “The government is doing its best but life isn’t obviously good here. It’s a tiny room, sometimes there’s no water. The drains often don’t work, especially when it rains,” says Sobaidah Comadug, a retired government employee who lost her husband and her hearing in the bombings.

“Why would I want to live here when I can go home? All I need is a little help to repair my home. Just give us what is ours. Marawi was beautiful enough, it doesn’t need any more beautification.”

All that is left is dignity, do not take that away

Comadug has just moved into a “temporary shelter”, a semi-permanent unit of about 150 sq ft. These are a step-up from the tent homes, but only just. The government is slowly moving the evacuees from tents to these shelters to improve living conditions, but it is only deepening fears of prolonged displacement.

“The homeowners of Marawi should have the choice of deciding if they want to live in their homes. We don’t want to live in temporary shelters. Compensate us for the damage and we’ll build our own homes. The government refuses to talk about compensation for the victims,” says the Sultan of Marawi, whose own three-storey home has been all but wiped out. “All that’s left is dignity, do not take that away,” he says.

Behind the eagerness to return home is the fear of losing it altogether. Property tends to be held communally by Muslim families, which means many residents have no individual land titles. And all this talk of a “new Marawi” – with wider roads, parks, modern facilities and even a new army base – only adds to the fear of losing private property to public utility. They do not understand why they cannot have a say in how the city is to be rebuilt, just as they do not understand why it was destroyed in the first place.

Untold destruction

“Why did you have to rain bombs on an urban centre with such a high population density? I hate to say this, but they bombed us because it’s a Muslim city and they think we Muslims are all terrorists,” says Samira Gutoc, organiser of civilian group Ranao Rescue Team.

Aerial bombardments started within three days of the beginning of hostilities, the day Ramadan began. Although the government ensured most inhabitants had left by the time, there were many who could not.

“We are talking thousands of civilians here, who were trapped,” says Gutoc.

Within weeks, the Commission on Human Rights was appealing to the government to stop. “The air strikes are a major factor in the internal displacement of civilians,” it said, causing the “destruction of buildings and civilian property” and resulting in the killing of “innocent civilians, including children, and even our own troops”. By then, 12 soldiers had died in “friendly fire”.

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) says it was left with no choice because it is not used to urban warfare. Clearing the city building by building, block by block, would make it a protracted war that neither the military or the country could afford.

“There’s little evidence the Philippine military was indiscriminately shelling or bombing the city. This wasn’t 1999 Grozny,” says Greg Wyatt, associate director of risk consultancy Pacific Strategies & Assessments. “The Philippine military doesn’t have heavily armed armoured vehicles like tanks that can attack sturdy and well-defended buildings. So it had to resort to artillery and air strikes.”

The level of destruction in Marawi, he says, resulted from the fact that each building in the downtown area was heavily defended by rebels. “That doesn’t, however, change the fact that the air strikes were deeply unpopular among the local population.”

The looting that followed, for which the locals accuse the men in uniform, did not help. The military has promised strict action against rogue soldiers if found guilty, but blames the militants and fleeing civilians for most of the looting.

“Military cars laden with looted goods were everywhere. They want us to believe that the Maute were stealing refrigerators and TV sets while waging jihad?” says Lininding of the Moro Consensus Group.

“And don’t get me started on UXOs. How come not one looter has tripped on an UXO yet? It’s a lame excuse for not letting people back in.”

There's too much drug blood on America's hands to lecture Duterte

Troubled past

For the military and the Maranaos, as the people in and around Marawi are called, this distrust is mutual. Local civic leaders blame the military for rushing into a war rather than asking them to negotiate with the Maute. The military blames them for not alerting the authorities about the Maute in time and for allowing the city’s descent into a lawless black hole that made it fertile ground for the likes of Maute and Hapilon.

“Guns, goons and drugs, that’s how local politicians operate here. You can’t run for even a village election if you don’t have at least 50 armed men on your rolls,” says a local military commander, who cannot be named because he is not authorised to speak with the press. His makeshift command office is a palatial home of a drug lord, now on the run, which was seized during the war.

Drugs are said to have been freely available in Marawi and kidnapping became a small-scale industry before the conflict broke out. The city had also developed a reputation as the top market for advanced guns, which were freely bought and sold here.

With one of the highest poverty rates in the country, young demographics, low economic opportunities, a tradition of vendetta and clan wars, preponderance of drugs and guns, cultural alienation of the Maranaos from the Philippines’ Christian majority, and a generational resentment over losing land to the Christians, Marawi’s Muslim youth became easy picking for fundamentalist recruiters.

Marawi might not have been paradise...but it was their own piece of hell, a pride that fed into Islamist sentiments

Islam came to the Philippines in the 1400s through the southern islands, long before the arrival of Christianity in the following century. A recent report by the country’s Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission says Christian dispossession of Muslim land through waves of state-directed migration from northern and central Philippines, especially since 1898, turned Moros – as Muslims are called in the Philippines – and indigenous peoples of Mindanao into a minority in their own land. This, it says, has been the major source of violence in the region and a potent recruitment trope for extremist groups.

“Marawi might not have been paradise, but having never been conquered by Spanish or American colonisers or resettled by Christian migrants, it was their own piece of hell, a pride that fed into Islamist sentiments,” says Conde of the Human Rights Watch, on the emotive appeal of Marawi among the Muslims.

What now for Duterte's China pivot as Marawi cements US importance for Philippines?

As far as the military is concerned, this idea of exceptionalism only turned Marawi into an island of unbridled crime and vice, which is now slowly being reversed with martial law and military presence.

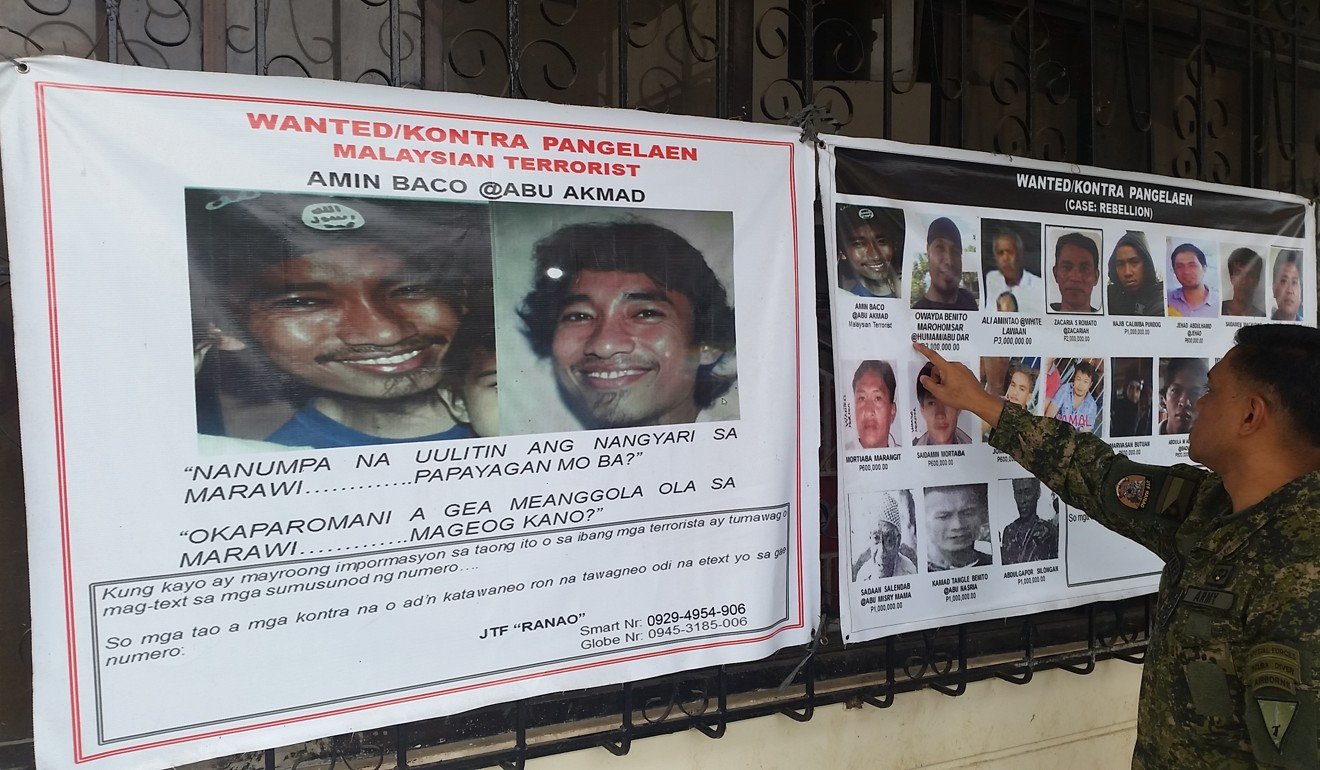

“Martial law is helping eradicate gun culture rampant earlier. Most residents here had firearms because of the culture of family feuds. There were killings in Marawi city every day, now it’s down to zero,” says Colonel Romeo Brawner. The residents, he says, are now cooperating with the military, helping it to catch the “remnants of Maute”, who still pose a threat along with foreign fighters and jihadi recruiters now preying on the frustration of the displaced community.

“But things are getting better,” he says. And the military wants to keep it that way, as it sees its presence as insurance against the risk of Marawi backsliding.

Plans are afoot to build a second military base in the city. The proposed blueprint for the city has land allocated for a military camp right outside the most affected area, says Asec Felix Castro, field office manager of Task Force Bangon Marawi, which is driving the redevelopment programme. “It’s up in the hills overlooking Marawi city,” he says.

But an enlarged military presence is anathema to the proud Maranao. “It’s an invasion. They are trying to take our land again. Marawi is the country’s only Islamic city, with 90 per cent of the population Muslim. You can’t sell pork here, you can’t gamble. It has never been conquered, now the Philippine military wants to change all that,” fumes Lininding.

Lasting peace

Ironically, plans for this greater military presence come at a time when lasting peace is within reach. The Philippines is sitting on the brink of an opportunity to end nearly two decades of Moro conflict, by enacting a law that will grant greater autonomy and self-governance to the Muslims with a sharia-like legal structure and their own parliament.

Called the Bangsamoro Basic Law, or BBL, it is the result of a peace agreement between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Manila in March 2014. It stalled as a result of the public backlash after 44 members of a special unit of the Philippine National Police were killed by Moro fighters in early 2015.

“BBL is the last chance for peace. It’s about correcting the historic injustices to the Muslim people who have lost land through generations of Christian settlement,” says Senen Bacani, a leading business personality who was a member of the peace panel that came up with the BBL framework.

“There’s been a lot of broken promises on the issue of autonomy. From Mindanao himself, Duterte is aware of these feelings, his grandmother was a Maranao. He doesn’t want to delay this any more. He knows very well that newer and more radical groups emerge whenever the peace process flags.”

Duterte has promised to resign if he cannot get BBL passed. His spokesman this week said Duterte would certify the BBL as urgent “any time soon”. Both the Senate and the House of Representatives have committed to pass it this month.

But there are murmurs of resistance from a section of politicians and the security apparatus who are against the provision of giving the new autonomous entity power over its own military and police. The Philippine National Police (PNP) and the AFP should continue to control the corresponding forces in the autonomous area to avoid “politicalisation”, PNP chief Oscar Albayalde said this week, echoing the view of some lawmakers seeking amendments to the BBL.

The Marawi war has created goodwill between the security forces and traditional Moro rebel groups such as the MILF, which sided with the military and helped evacuate civilians. But the war has also renewed fears of Islamist terror and validated the need for a stronger military presence in the region to ward off a new threat of global jihad. For Duterte, that poses one of his toughest political challenges – carrying out his BBL promise in a way that is acceptable to the Muslims, the Catholic majority, and the powerful military and police forces.

Watch: Philippine city of Marawi destroyed after long-running conflict

The geopolitics of Marawi

The security issues posed by Marawi have implications beyond domestic political contests. It goes to the heart of the Philippines’ civil-military relations and the emerging geopolitics of the region.

Duterte’s time in office has seen him make greater moves towards befriending China and distancing the Philippines from its traditional ally, the US, often in colourful language. Just last month he launched a tirade against the US, saying the CIA should be blamed if his plane ever crashes.

Setting aside the conflict over overlapping claims in the South China Sea, Duterte has sought to engage China both diplomatically and economically, making it a key component of his “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure drive. “More than anybody else at this time of our national life, I need China,” he said last month.

“Duterte never made any bones about his displeasure at the presence of the US military here. As mayor of Davao, Mindanao’s biggest city, he banned the annual US-Philippine military exercise. He also rejected the US offer to establish a drone base there for Mindanao,” says Roland Simbulan, author of The bases of our insecurity: A study of the US military bases in the Philippines.

But Simbulan also points out that the generals Duterte has appointed in the cabinet are all known to be close to the US military, especially Delfin Lorenzana, secretary of national defence.

“US exerts considerable power in the Philippines through the military. More than 95 per cent of the weaponry comes from the US. All key officers of the AFP are trained in top US military academies and return with the same security orientation as the US, which is passed down the ranks,” he says. “What Duterte is doing is maintaining this status quo, while creating new openings with China and Russia.”

Duterte often speaks about the need to send officers to China for training. After Marawi, China and Russia supplied weapons to the Philippines for the first time in its history. Duterte also tends to single out China’s help in the Marawi war, pointedly mentioning that Hapilon was killed with a Chinese rifle.

But given the military’s historical power in the Philippines, especially since the Marcos era, Duterte also has to be mindful of its sensitivities. After the war broke out, the president first said there would be no need to take American help, only to reverse his position when contradicted by Lorenzano. He had to do a similar flip after asking US soldiers to leave Mindanao.

Forging peace with Moro and communist rebels has been the central plank of Duterte’s presidency. Asking soldiers to make peace with the same people they have been fighting all their life is difficult enough, he does not need angry generals to boot. And there would be some, if the military is turfed out by the new autonomous government entity in the south.

According to Simbulan, the US began to involve itself more with Mindanao since the Abu Sayyaf group attacked American citizens in 2003, the same year the US invaded Iraq. By 2005, he says, some 600 US personnel, mostly from US Special Forces, had been deployed in Mindanao, focusing on Muslim areas.

“If BBL goes through, it would remove the rationale or legitimacy of US military presence in Mindanao,” says Simbulan, noting the US has substantial interests on the giant island because of the large American agricultural and mining companies that operate there. A larger AFP presence in Marawi on the other hand would secure US military interests in the region, thanks to the Philippines’ Visiting Forces Agreement with the US as well as the AFP’s close institutional linkages with America’s military.

Philippines' Rodrigo Duterte wants to be friends, why isn't China playing ball?

Losing ground

Arsan Sali, who has lived in a shack next to the tent camp since losing his home in Marawi, is anxious about losing turf too.

“UXO is not a real threat. Let us go back to Marawi, that’s where we’ll start over again. That’s where our ancestors were buried, that’s where we will die,” says the 43-year-old descendant of a local sultanate, who now repairs television sets to make ends meet.

Maranaos, he says, have a special place for Marawi in their hearts. Nowhere else is good enough. And it makes him angry that people who have no connection to this sacred land are being invited in to build the city while its own languish on its margins.

“It’s a land grab, they’ll make money off our land, they’ll rob us of our livelihoods.”

A community leader, Sali is more vocal than the others. Living under the shadow of the gun, most prefer to play along, even if with Girl in the mirror. Others, like the Usmans, toil away in silence to fix their broken lives to keep their Faisals going. Many more, living at the mercy of relatives and friends, have had to choose mute subservience as survival strategy.

“The silence of the people is a ticking time bomb,” warns Lininding. ■