What’s the ‘dirty secret’ of Western academics who self-censor work on China?

As concerns grow over Chinese influence in Australia, critics say academics eager to maintain access to the country are increasingly minded to avoid criticising Beijing

But then Leibold found two fellow academics from European universities had suddenly had second thoughts about publishing their work alongside his. A discussion ensued and collectively they decided about a month ago not to submit any of their papers. Leibold’s piece would have to wait. “We had a long conversation. They were concerned they wouldn’t be granted visas to China. It was self-censorship,” said Leibold of La Trobe University. “It’s regrettable this happened.”

Why China hurts itself more than others with censorship

Leibold’s experience highlights an increasing concern in Western academic circles regarding the growing reach of Beijing’s influence abroad. Critics say academics are increasingly censoring themselves to avoid criticising Beijing out of a fear they could lose access to the country. While Beijing’s hand in this process is not always overt, its critics say this is just one way in which China suppresses criticism and exerts its influence abroad.

And their experience is far from unique. Leibold said some researchers in Chinese universities had withdrawn from joint projects with foreign institutions after being warned by authorities that their projects were being monitored. He said some Western academics had become “spooked” during trips to the country when they were stopped by Chinese security agents and asked about their studies. In one case, he said, an academic was told to give the agents a copy of his doctoral dissertation.

What Chinese, Singaporean universities can teach us about academic freedom

“I’m aware of a number of Western-based academics who have shifted the focus of their research away from sensitive topics … due to direct intimidation or the fear of intimidation,” he said.

DIRTY SECRET

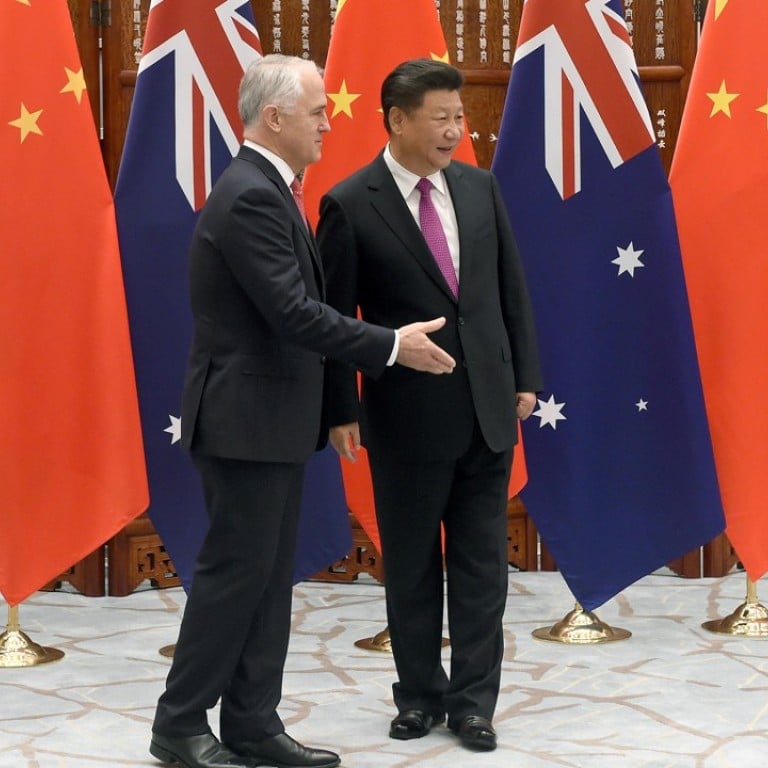

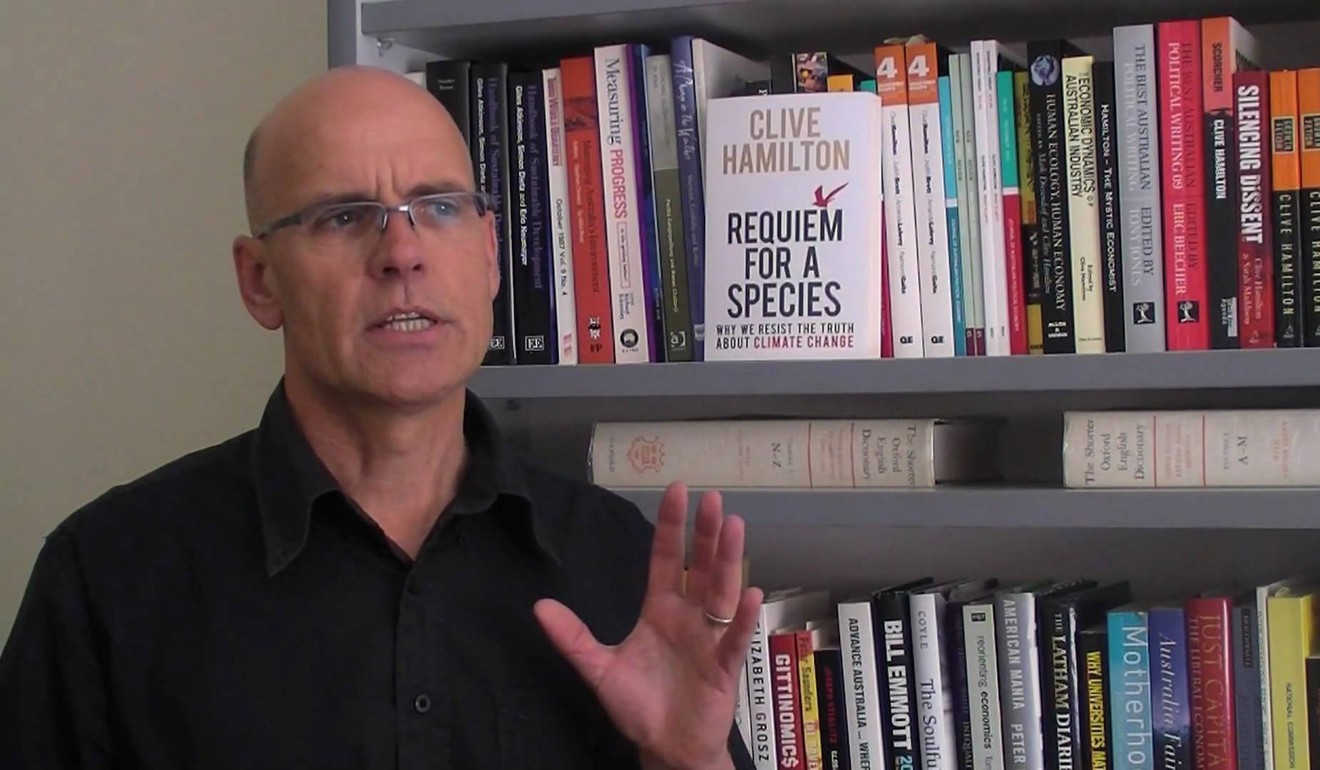

Turnbull’s plans were announced just a month after Australian academia was rocked by an 11th-hour decision by Allen & Unwin to cancel its publication of Silent Invasion, a book by the Australian academic Clive Hamilton that claimed the Chinese government was eroding Australian sovereignty by controlling Chinese businessmen and students in the country, as well as manipulating Australian politicians into taking pro-China stances. Hamilton found a new publisher, Hardie Grant, and the book came out in February. Despite incurring the wrath of Beijing, the author has stuck to his guns, writing this month that “scholars who work on China know that continued access to the country requires them to play by Beijing’s rules, which for most means self-censorship – the dirty secret of China studies in Australia”.

Still, Hamilton can point to plenty of academics who hold similar views.

Feng Chongyi, a China expert at the University of Technology Sydney who has found himself at the sharp end of Beijing’s censorship efforts, said Australian academics had become more reluctant to criticise China in recent years. “They try to avoid sensitive topics and toe the party line, or not to cross [Beijing’s] red line,” he said.

“I started by talking about the freedom of publication in Australia and was very soon told to stop. I was just a few minutes into my introduction,” recalled Feng.

Yet some academics play down the experiences of people like Hamilton and Feng. Jieh-yung Lo, a commentator on Chinese-Australian affairs, said Hamilton was guilty of “fear mongering” and had spoken only to Chinese Australians who held anti-China views rather than seeking a diversity of opinion.

Last month, about 80 academics penned an open letter denying that Australian experts on China had been “intimidated or bought off” by pro-China interests. “We see no evidence … that China is intent on exporting its political system to Australia, or that its actions aim at compromising our sovereignty,” the letter read.

We see no evidence ... that China is intent on exporting its political system to Australia

Jonathan Benney, a Chinese studies lecturer at Monash University, was among those who signed the letter. He said it was true that academics faced pressure from Chinese media in Australia and from individual Chinese to write positive articles. But he did not think academia as a whole had succumbed to the pressure and said many scholars were still critical of China. He said Chinese students – whom he admitted were “economically important” to university budgets – often held different opinions to him, but were usually willing to listen to him in class.

Can Cambodia’s censors keep a lid on its steamy social media?

A recent alumni from Benney’s university, a 26-year-old Chinese, defended his alma mater – and Australian academia more generally as recognising and accepting a plurality of views. He said, for example, that his teachers would refer to Taiwan – regarded by Beijing as a renegade province rather than a separate nation – as an “independent economic entity”. The student said this was a neutral and professional way to discuss the island.

“Chinese students in Australia hold diverse political views. There are students who think that China’s political system allows the country to be run efficiently,” he said. “For me, I value democracy.” ■