What a nude painting of Park and an awkwardly placed THAAD missile says about Korean politics

Controversial political art is nothing new for South Korea, but what some call a sexist depiction of the scandal-hit president has struck a nerve at just the right (or wrong) time

A painting of South Korean President Park Geun-hye in the nude has triggered a national debate about the limits of artistic expression in a democracy and the use of sexism to debase political opponents.

The latest in a long, proud and even strident line of controversial expressions is Lee Koo-young’s Dirty Sleep, depicting Park as Venus from Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, with a Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) missile between her thighs.

Put on display at the National Assembly Hall in Seoul in January as part of an exhibition organised by opposition lawmaker Pyo Chang-won, it has since been ripped off a wall and stomped on by Park supporters – prompting the National Assembly Secretariat to bring a halt to the exhibition. “Anyone who dislikes the painting has the right to express his or her opinion,” Pyo said. “However, using violence and destroying it is violating the law and constitutes a crime. Since such a criminal act was caused by hatred and targeted a piece of art, with the support and cheering of a crowd, it can be regarded as cultural vandalism.”

The painting puts a nude Park in repose in a setting reminiscent of Manet’s Olympia, with Park as the prostitute and her confidante, Choi Soon-sil (who has been charged by prosecutors for intervening in state affairs), as the servant bearing a basket of needles. Behind them, outside a window, a ferry sinks. The ferry references the MV Sewol ferry disaster of 2014 in which about 300 people died, mostly secondary school children; the needles reference claims that Park received hundreds of Botox injections, including some on the day of the ferry tragedy; the missile references the Park government’s decision to install the US anti-ballistic missile system on its territory, much to the displeasure of China, which has made clear the issue could destroy relations between Seoul and Beijing.

South Korea, US forces begin joint military drills amid THAAD missile tensions with Beijing

The controversy is the latest involving the embattled president, who was impeached over the scandal surrounding her confidante Choi.

This month, more than 450 Korean artists filed a lawsuit against Park, her former chief of staff, Kim Ki-choon, and former culture minister, Cho Yoon-sun, for implementing a blacklist that sought to suppress artists deemed critical of the government.

In January, Cho became the nation’s first acting minister to be arrested over the blacklist. The list included 9,473 artists who had supported Moon Jae-in during the 2012 presidential election, or Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon during the 2014 mayoral election or criticised the government’s botched response to the Sewol ferry sinking.

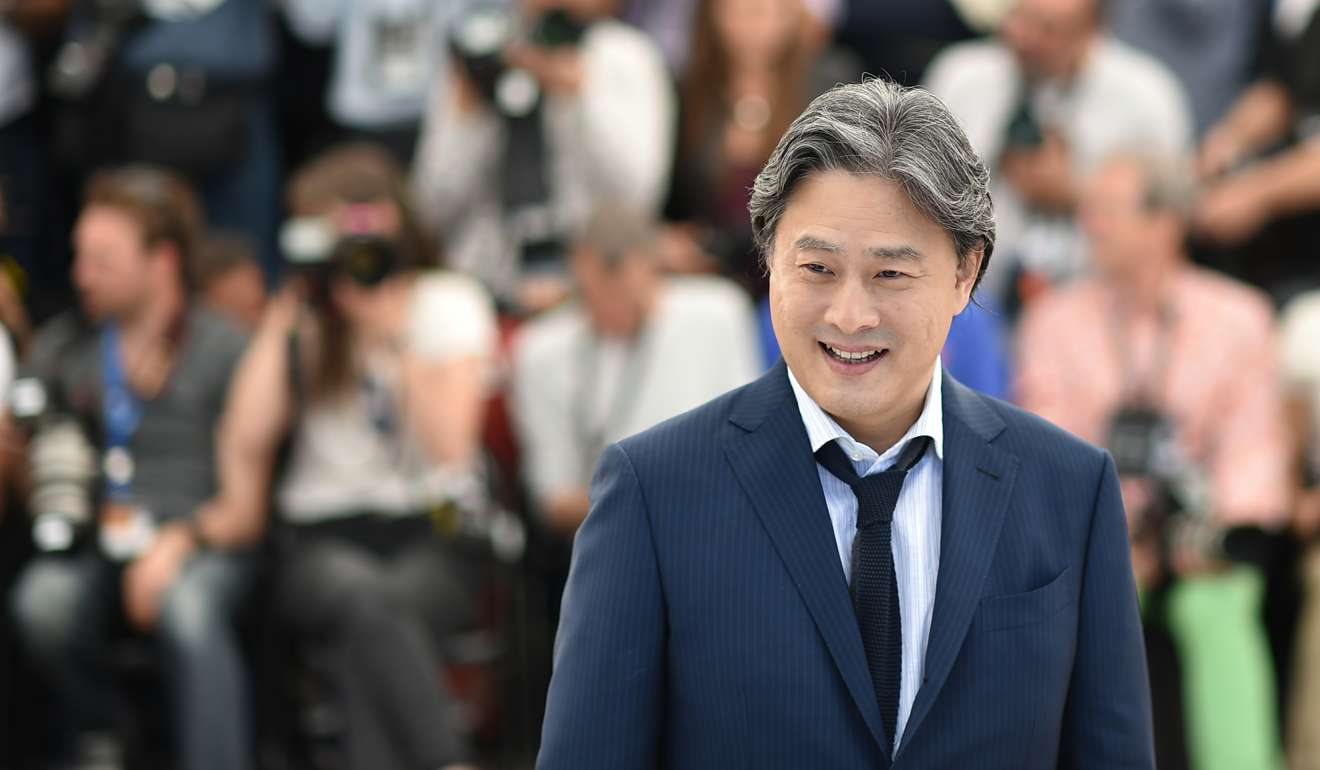

Among those on the list were Park Chan-wook, the director of mystery thriller Oldboy, and Han Kang, the first Korean to win the Man Booker Prize.

The blacklist came to be seen as a plot by Park to label such artists “reds” and deny them government sponsorship or other opportunities. Such red-baiting harkens back to the time of Park Geun-hye’s father, Park Chung-hee, who famously shut down the People’s Daily in May 1961 after it published a series of editorials criticising the government, and then had its owner publicly executed on charges of collaborating with North Korea.

Red-baiting doesn’t lead to public executions anymore, though it still forebodes violence. In 2014, the artist Hong Seong-dam’s painting of Park as a scarecrow facing parents of the Sewol ferry victims was censored at the Gwangju Biennale, and conservatives later harassed Hong at his home, calling him a “communist painter”.

Political art is nothing new in South Korea. After the Gwangju massacre in May 1980, in which government troops killed hundreds of people protesting against military dictatorship, artists formed the Minjung cultural movement, which openly criticised the government and was a major force in ending the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee, father of the current president.

South Korea closes biggest dog meat market ahead of 2018 Winter Olympics

There was Shin Hak-chul’s 1980 work, Landscape I, depicting a red wasteland of trash and corpses with a single arm rising out of the rubble, holding a knife. Or Hong Song-dam’s 1981 Kwangju, showing a child leaning over the dead body of a pregnant woman. In 2012, Lee Ha was fined for publicly posting images he’d made of former dictator Chun Doo-hwan in pink handcuffs. Lee has also painted Park playing with dogs (her cabinet members) while an origami boat (the Sewol ferry) sinks in the distance. He has been harassed and arrested almost as many times as China’s Ai Weiwei.

Given Korea’s history of political art, why did Dirty Sleep cause such outrage? According to Sim Yeong-eun, a curator at Leeahn Gallery in Seoul, in Korean art “nudity is not so shocking”. Indeed, the gallery itself has a statue of a male nude by Antony Gormley on its roof. But Sim said that did not mean the same thing applied to people outside the art community – clearly not politicians in politically charged times. Park and her supporters are awaiting the verdict of a constitutional court on her impeachment in December following the influence-peddling scandal regarding Choi that prompted weeks-long street protests.

South Korea's Lotte Group offers golf course for THAAD missile deployment

The furore over the painting also points to a deeply ingrained streak in Korean society: misogyny. Park Kyung-mee, spokeswoman of the opposition Democratic Party, told the local media: “Although the artwork was intended as satire, we concluded that it was inappropriate to have such a painting exhibited at an event organised by a lawmaker. Pyo defended himself citing freedom of expression. But the painting is also anti-feminist.”

As a commentator points out in Korea JoongAng Daily, men in Korea are not ridiculed in this fashion and the response to the painting was no less sexist. Online reactions didn’t target Pyo, but cropped the face of his wife and underage daughter onto the painting’s nude body. Female protestors gathered before the National Assembly chanting, “Pyo, we will strip your wife naked, too,” rather than “Pyo, we will strip you naked, too.” ■