Thai migrant workers demand action as berry-picking hardships in Finland go unheard

- Thousands of Thai workers have been lured to Finland and Sweden over the past decade with promises of earning thousands of dollars to pick wild berries

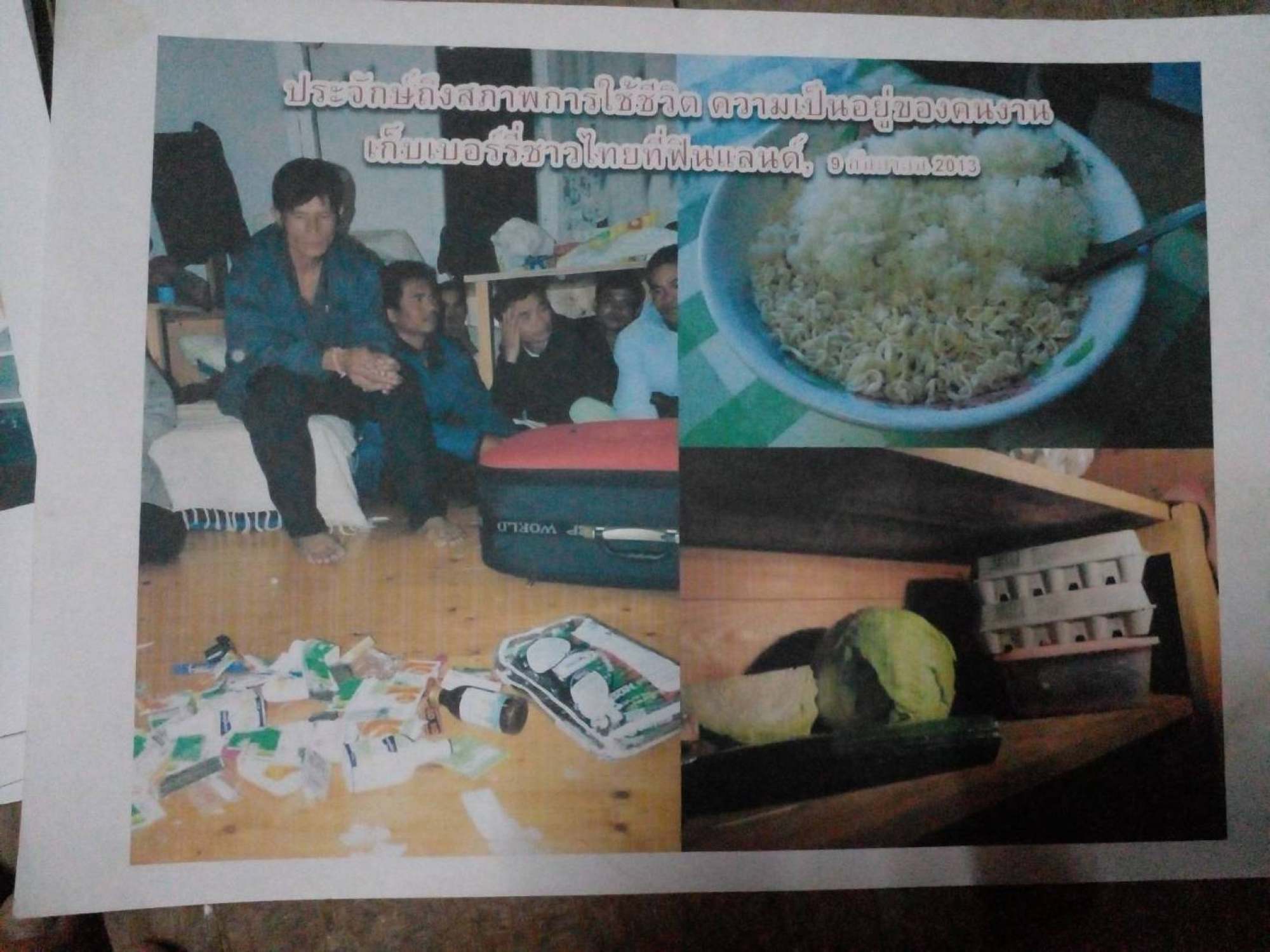

- Instead, they were faced with inhumane working and living conditions, and rarely received the money they were owed, advocates say

“A recruiter came into the village and said everyone would be paid between 100,000 and 200,000 baht (US$2,660-US$5,320) in exchange for two months of picking wild berries there,” said the Thai cassava farmer, who worked in the Nordic country between July and October that year.

He had a feeling it was too good to be true, but the salary was irresistible. The annual income for an agricultural household in Thailand is about 400,000 baht (US$10,500).

I worked from 4am to 11pm, which is when daylight lasts in Finland

Thousands of Thai workers arrive in Finland and Sweden every year only to face inhumane working and living conditions. They are then ripped off through a human trafficking process long overlooked by authorities on both sides of the world, advocates say.

Awaiting justice

Praisanti, along with more than a dozen other berry pickers, last month submitted a petition to several agencies, including the Thai parliament and the Thai labour ministry asking for tougher regulations on local recruiters and to speed up the compensation and prosecution in their cases.

Teerasak Pakdinopparat, a Thai migrant worker who travelled to Finland in July and returned in October, was among those submitting a petition. Out of the few months he worked picking berries “from sunup to sundown” he went home with only one-tenth the amount he was promised.

“I worked from 4am to 11pm, which is when daylight lasts in Finland,” said the 44-year-old. “I was told before I travelled that I had to turn into cattle to handle such hard work.”

Will Thai visa scheme for wealthy foreigners be ‘a big win’ for economy?

The payment slip showed Teerasak picked 1,681kg of blueberries and almost 700kg of lingonberries altogether worth €2,772 (US$2,700), but after expenses such as rent (€7 a day for 65 days), food, car, gas, clothing, a Sim card and a company loan, he was left with just €247 (US$240).

“Up to six people shared a 3-by-3-metre space. There were just three restrooms for over 100 of us who stayed in the same camp. Each camp was overseen by a few Thai people who were agents and managed how much berries the company would buy from us,” said Teerasak.

Back in September 2013, Praisanti knew that he and fellow migrants were deceived. They were originally promised €1.8 per kilo for blueberries and €1.4 per kilo for lingonberries, but the company usually paid €1-1.20 for both, citing market prices at the time.

Moreover, there were fewer berries to pick as more labourers moved to work in the same area. Praisanti and other migrants often had to drive farther – one time 300km from the Finnish town of Juva where they were based – to seek wild berries, doing so at their own expense.

Australia lures Asians to farm labour with path to permanent residency

More than a month after arriving in Finland, Praisanti became one of among 50 Thai workers who revolted by refusing to work and demanded a one-month payout before returning to Thailand.

A compromise was reached during a negotiation presided by staff from the Thai embassy and a representative from the Finnish company Ber-Ex. In the end, 30 people including Praisanti were each paid €1,300 (US$1,270), which was close to one month’s salary originally promised. The company said the other 20 still owed them money in the form of a loan.

Injustice continues

Labour activist Promma Phumipan said there were currently up to 18 Thai job agencies recruiting people to pick berries in Sweden and Finland. While the agencies are legitimate, their process involved deception, he said.

“The company might recruit 20 people legally, but it could add another 100 people on tourist visas to pick as many berries as possible,” he said.

Promma said Teerasak and his group’s complaint in Finland months ago resulted in the imprisonment of a CEO of a Finnish company and a Thai recruiter by the name of Kalyakorn.

A paper obtained from the Thai labour ministry by Promma showed that in 2019, Kalyakorn represented three Finnish companies that collectively requested about 800 workers.

According to Finland-based Thai human rights activist Junya Yimprasert who helped both Teerasak and Praisanti, over 110,000 workers went to Finland and Sweden for the berry-picking jobs between 2005 and 2022. Over 4,000 travelled to Finland and just under 5,000 went to Sweden this year.

However, any involvement from the Thai embassy focuses on sending workers back to Thailand instead of helping them with the legal issues in Finland, said Junya.

Promma is also collecting statements from workers to help with the prosecution of a Finnish executive and Kalyakorn in Finland, although from Praisanti’s past experiences, company executives and recruiters are rarely convicted. After returning to Thailand in October 2013, Praisanti lodged a complaint with the Department of Special Investigation against a local recruiting company and three of its recruiters. So far, no prosecution has been made.

“Workers who travelled with me then are now in different parts of Thailand so it is difficult to get together to push the case,” he said. “But the three recruiters still send people to Finland and Sweden every year and it hurts me inside to see that.”