Did Kim Il-sung imagine his ‘martyred’ Chinese best friend Zhang Weihua?

- In Kim’s memoirs, Zhang Weihua is hailed as a saviour who gifted guns to anti-Japanese guerillas and took his own life to save the North Korean leader

- But as is so often the case with the hermit kingdom, the truth of the matter is difficult to discern amid all the embellishments and political propaganda

The pair, according to two chapters devoted to the subject in Kim’s memoirs With the Century, remained friends right up until the 25-year-old Zhang took his own life – 83 years ago on Tuesday – in a bid to protect the future “eternal president” of North Korea from capture by the Japanese, leaving behind a wife and two young children.

Yet the details of his story are hard to verify, Korean experts say, as the authorship of Kim’s memoirs is disputed and many parts were likely embellished or skewed for the sake of political expediency.

North Korea’s future leader was born Kim Song-ju on April 15, 1912 in Pyongyang, the eldest of three sons who followed his family to Manchuria – now northeastern China – where he attended primary school, according to Suh Dae-sook, a professor emeritus of political science and the former director of the Centre for Korean Studies at the University of Hawaii, in his book Kim Il-sung The North Korean Leader.

Kim wrote in his memoirs that he first met Zhang, the son of a rich landowner, at Fusong Senior Primary School No 1 after his father escaped the Korean peninsula once it fell under Japanese control. He remarked on how strange it was that “friendship sprouted and blossomed” between someone such as himself – “an unlucky boy from a ruined country” – and “the son of a millionaire”.

“We frequently played tennis in the schoolyard and went swimming in the River Songhua,” Kim wrote, adding that the pair would often visit each other’s homes and eat together as their families knew each other well.

Kim’s father – who Suh said spent most of his life in Manchuria operating a herbal pharmacy and died in 1926 at 32 when Kim was only 14 – apparently treated Zhang’s father for an illness at some point, with the two later bonding over calligraphy.

The elder Zhang not only helped the Kims get official approval from the local authorities to live in Fusong, he also sent money and food after the father’s death “worrying about my mother who was going through hardships supporting children as a widow,” Kim wrote.

INTO ADULTHOOD

Kim’s formal education ended in 1929, according to Suh, when he was expelled from school at the age of 17 after attending a banned communist youth organisation meeting.

By the time he was 20, as Louisiana State University professor Bradley K. Martin wrote in Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader, the war games of Kim’s boyhood had become “deadly real”.

He was now a guerilla leader fighting the occupying Japanese, having risen through the ranks to command his own unit and answering to a Chinese nationalist commander operating in the area, Martin wrote.

Zhang is said to have begged to join the unit, but Kim refused – asking him to stay and gather information instead.

Is North Korea gearing up to unveil new missiles before US election?

In his memoirs, Kim said that he was worried Zhang might not be cut out for all the trekking that guerilla warfare entails.

“So you should help our work as much as you can by running a photo studio or teaching in school rather than undergo hardships in mountains. Your reputation as a rich man’s son is very useful. It can hide your revolutionary activity,” he recalled telling Zhang.

SAVING KIM

According to the memoirs, Zhang first saved Kim’s life in 1930 by allowing him to seek refuge in a first-class train carriage on a train when he found himself being pursued by the Japanese military police.

When the train arrived at the station, Kim said Zhang whisked him away in a horse-drawn carriage before the pursuing police realised what had happened.

Zhang is also credited with donating dozens of rifles to Kim’s guerilla unit, without which “there would not be a Korean People’s Army today”, the North Korean leader said in 1993 – one year before his death – at a meeting with Zhang’s descendants, Chinese author Lu Minghui wrote in Kim Il-sung and Zhang Weihua: Life and Death Across National Boundaries.

Lu said Zhang obtained the rifles by trading tobacco with the troops of a Manchurian warlord, though Kim recalled that some had come from the private armoury of Zhang’s father – it not being uncommon for wealthy Chinese families to have private armies at the time.

The weapons proved an invaluable gift, especially as Kim and his comrades grew low on supplies, with provisions often exhausted and clothes tattered in their fight against the Japanese, Martin wrote.

Zhang sent enough money for the fighters to buy new uniforms and other essentials, and ensured goods such as cotton, shoes, socks, underwear and food “flowed ceaselessly into the secret camps of our unit,” Kim wrote, “and provided strong economic support to the activities of the revolutionary army in the Fusong area”.

While Kim was away, Zhang married and started a family. At their final meeting, they joked about how Kim should be with someone as beautiful as Yang Guifei, an imperial consort of the Tang dynasty renowned for her beauty.

“His smile at that time remains in my memory as an indelible image. This was the last time I saw his smile,” Kim said in his memoirs.

ZHANG’S DEATH

Zhang was arrested in 1937 after Japanese authorities learned of his connections to Kim, the pair having apparently been betrayed by their primary school classmate Jong Hak-hae.

To get him to reveal Kim’s whereabouts, Zhang was interrogated but he “faced the torture in silence” until he was eventually granted a short reprieve after his father bribed the police, Kim wrote.

While back at home on release from interrogation, Zhang wrote Kim a note warning him that Japanese spies were after him, then took his own life by swallowing a corrosive substance used in film development.

The image of Zhang was most expedient because he served as a good example for Kim’s capability of maintaining warm and loyal friendships

The father to a four-year-old son and newborn daughter “died a heroic death at an early age for me, and for the headquarters of the Korean revolution”, wrote Kim, recalling how he could not sleep or eat for several days after his friend’s death.

“I felt an aching void and shock in my heart; my soul seemed to tumble into an abyss, as if a part of the world had collapsed near me.”

According to social anthropologist Sonia Ryang, author of Reading North Korea, an Ethnological Inquiry, the incident tormented Kim for the rest of his life.

“Many decades later, he built a monument to Zhang with his own Chinese inscription,” she wrote, referring to a memorial made by craftsmen in North Korea and shipped to Fusong in October 1992, on the 55th anniversary of Zhang’s death.

HOUSEHOLD NAME

For laying down his life in the name of the country’s founder, Zhang has become a household name in North Korea, where he is honoured as a hero.

In museums throughout the land, he is revered as Kim’s comrade-in-arms, and a “great internationalist fighter who sympathised [with] and supported the anti-Japanese struggle of the Korean people”.

“Zhang’s distinguished services occupy an honourable place both in the history of the Chinese Communist movement and in the annals of the anti-Japanese revolution of our country,” Kim wrote, saying he served as a symbol of friendship between North Korea and its neighbour to the north.

Back in China, however, Zhang’s exploits are almost unheard of – except perhaps by those in Jilin province who remember when Kim finally found and met his old friend’s descendants back in 1985.

The family had fallen on hard times since Zhang’s death, targeted for being rich landowners in a newly communist society, with his widow resorting to washing clothes and selling pancakes just to make ends meet, Chinese author Lu said.

Kim wrote that he worried about Zhang’s family whenever China “launched a campaign of social upheaval and movement” such as the Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward, and from 1985 he began inviting them to join him in Pyongyang as state guests.

Upon the first visit of Zhang’s son Jinquan and daughter Jinlu, Kim wrote that he was so excited at first that he could not speak, before regaining his composure and welcoming the pair in Chinese while explaining that he was a little rusty for lack of practice.

“Some people say that it is a breach of conventions for a head of state to speak in a foreign language in a diplomatic conversation, but I didn’t care. Zhang’s party was not on a diplomatic visit, and I hadn’t invited them for diplomatic reasons,” Kim wrote.

“What was the use of diplomatic conventions when I was receiving the children of my comrade-in-arms?”

Kim even wrote that he told Zhang’s children: “You grew up as fatherless children. From now on I am your father.”

On another visit in 1987, Jinquan brought more family members along including his granddaughter Mengmeng who was then 5 years old.

In his memoirs, Kim wrote: “Mengmeng, I am the elder brother of your great-grandfather. Holding you in my arms, I feel a lump in my throat as I yearn for your great-grandfather. He greatly loved children. If he were alive, how much he would love you! But he sacrificed himself for my sake, before he had reached the age of 30. I don’t know how I should repay him.”

Jinquan, in his own book about the experience, remembered his family being treated like honoured guests in North Korea, bestowed with expensive gifts and being given a plane and special train for their exclusive use. Kim, he wrote, would spend hours talking about the past, and went out of his way to ensure Zhang’s grandchildren received special treatment when they studied at the Pyongyang University of International Affairs.

KIM’S NOSTALGIA

Looking back at his early life from near its end, Kim described Fusong as a “den of warlords” where he had been arrested by the authorities and held in custody.

“But I loved this town as much as ever, because a part of my childhood had been spent there, and my father’s grave and dear Chinese friend Zhang Wei-hua were there,” he wrote, adding that Zhang still occasionally appeared in his dreams.

In his book, Lu wrote that when reminiscing to Zhang’s descendants, Kim recalled enjoying eating dumplings cooked by Zhang’s mother during his childhood days in China, and how Zhang in turn would savour the cold noodles served round at Kim’s house.

In the closing chapter on Zhang in his memoirs, Kim said he wished he could visit Fusong one last time to pay his last respects at his friend’s grave. He would die in July 1994 without his wish being realised.

POLITICAL EXPEDIENCY

Few historians dispute that Zhang existed or that he was an acquaintance of Kim’s, but the exact nature of their relationship will likely never be known thanks to the Orwellian nature of the North Korean regime.

“For any text that is produced in a propaganda-dominated society, where editorial direction and content are firmly in the hands of the state, it is expected that historical facts will be presented so as to align with a version of the truth acceptable to the regime,” said Ryang, the social anthropologist.

Kim’s memoirs were always intended as propaganda, published with the “specific target of glorifying” him, said Fyodor Tertitskiy, senior researcher at South Korea’s Kookmin University. “Thus the book is much less about how the events of the 1930s unfurled and mostly about how Kim wanted them to be.”

Then there is the fact that much, if not all, of what appears in Kim’s book was ghostwritten, recalling events that oftentimes “simply never happened”, according to Balazs Szalontai, a professor of North Korean Studies at Korea University in Seoul.

China and North Korea: the reasons for Japan’s tighter tech access rules?

Szalontai said Zhang did not appear in one of Kim’s speeches until November 1, 1968 – a full 31 years after his childhood friend’s death – even though the North Korean leader had previously spoken extensively about his time as a guerilla fighter.

The next time Zhang was mentioned was in 1983, followed by another long gap until 1991, Szalontai said, both times in passing – mainly as examples of how the wealthy can be as patriotic as the poor, and of how Chinese sympathisers had armed Korean guerillas.

“Zhang’s family, being both Chinese and rich, neatly fit both formulas,” Szalontai said, adding that in the first reference, Kim’s emphasis was on how the guerillas had “educated” and taught Zhang to be a revolutionary, with no mention of how he and his father had saved Kim’s life.

“Thus, I am inclined to think that Kim’s emotional connection to Zhang may not have been as strong as he claimed in his memoirs from 1991 to 1994, but he rather found this memory politically useful for multiple reasons,” Szalontai said.

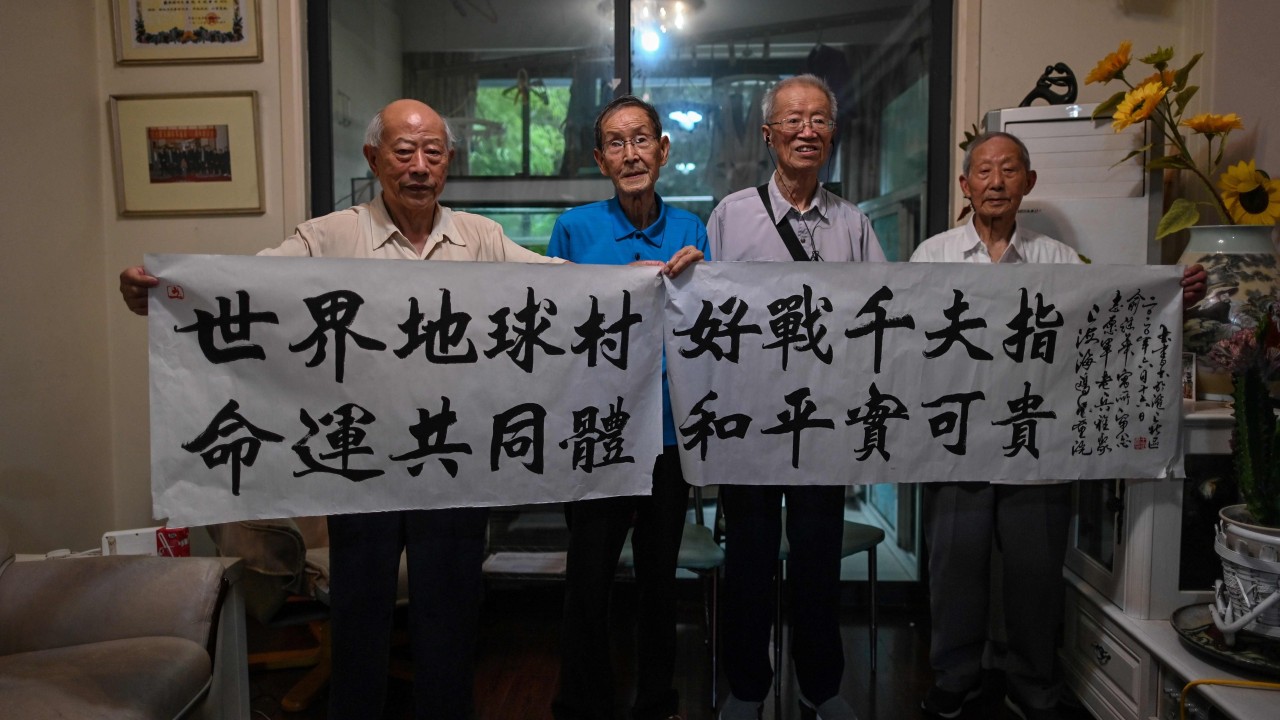

02:13

Chinese veterans of Korean War call for peace as tensions with US mount

Against this backdrop, Kim was keen to seem tolerant “so as to make a good impression on South Korean public opinion, and refute the bad international image of North Korea,” Szalontai said.

The Soviet Union had also just collapsed, making China even more important for North Korea’s security than before and pushing Kim to cultivate better relations with Beijing.

“One way to achieve this was to emphasise the long historical traditions of Sino-Korean friendship and the partnerships between the Chinese Communist Party and the Korean Workers’ Party,” Szalontai said.

Zhang is still a part of North Korea’s political narrative, then, because of his usefulness – but also because he could never threaten Kim’s position.

“The image of Zhang was most expedient because he served as a good example for Kim’s capability of maintaining warm and loyal friendships, yet at the same time he passed away so long ago that he couldn’t be regarded as any sort of alternative, rival, or challenge to Kim,” Szalontai said.

In North Korea, those who did threaten Kim were purged – “erased from history and their feats or names never mentioned again”, as Szalontai puts it.

While Kim’s memoirs may be an unreliable source of insight into the North Korean founder’s “true personality”, their description of his relationship with Zhang do at least illuminate how nuanced and sophisticated the regime’s propaganda can be.

“Creating a positive image for Kim, especially one that is potentially attractive to a foreign audience, required much more than presenting him as a great commander and an all-wise genius,” Szalontai said.

By making the “smart” decision of having him appear modest and even self-effacing – rather than the tyrannical head of a nationwide personality cult – Szalontai said the memoir’s authors humanised Kim through his relationship with Zhang, safe in the knowledge that any boyhood transgressions would not irreparably damage the great leader’s reputation.

POSTSCRIPT

On a visit to Fusong about 18 months ago, Zhang’s former residence could still be seen – though much grander and better maintained than earlier photographs had depicted it.

Passers-by confirmed that the house once belonged to “the Zhangs whose patriarch saved the life of North Korean leader Kim Il-sung”, but said the family had since moved elsewhere.

Some speculated that the Zhangs had grown rich after being given “exclusive trading rights” with North Korea, while others recalled the house being turned into an informal museum to Kim and Zhang’s friendship for a time by Zhang Jinquan.

Neighbours said that both the house and Zhang’s grave had been renovated some years ago with funds from North Korea, which was allegedly also the source of the tiles on the house’s roof.

In his book, Lu wrote that Kim did indeed give Jinquan 10,000 yuan (about US$71,000 today, accounting for inflation) in 1985, despite the latter’s reluctance to take it. Upon returning to Fusong, Jinquan used the money to renovate both the grave and the house, turning parts of the latter into a “Kim Il-sung Memorial Museum”.

Zhang Weihua’s grave – located on the outskirts of town in a large compound with walls built from stone and granite – is well-maintained, standing out from the rundown houses nearby.

Locals said the gates are only opened during anniversaries and on special occasions such as Qingming (grave-sweeping festival).

Plaques adorn the wall outside, stating the site is “Zhang Weihua Martyr’s Mausoleum”, and a “national patriotic education base” of China’s Jilin province.