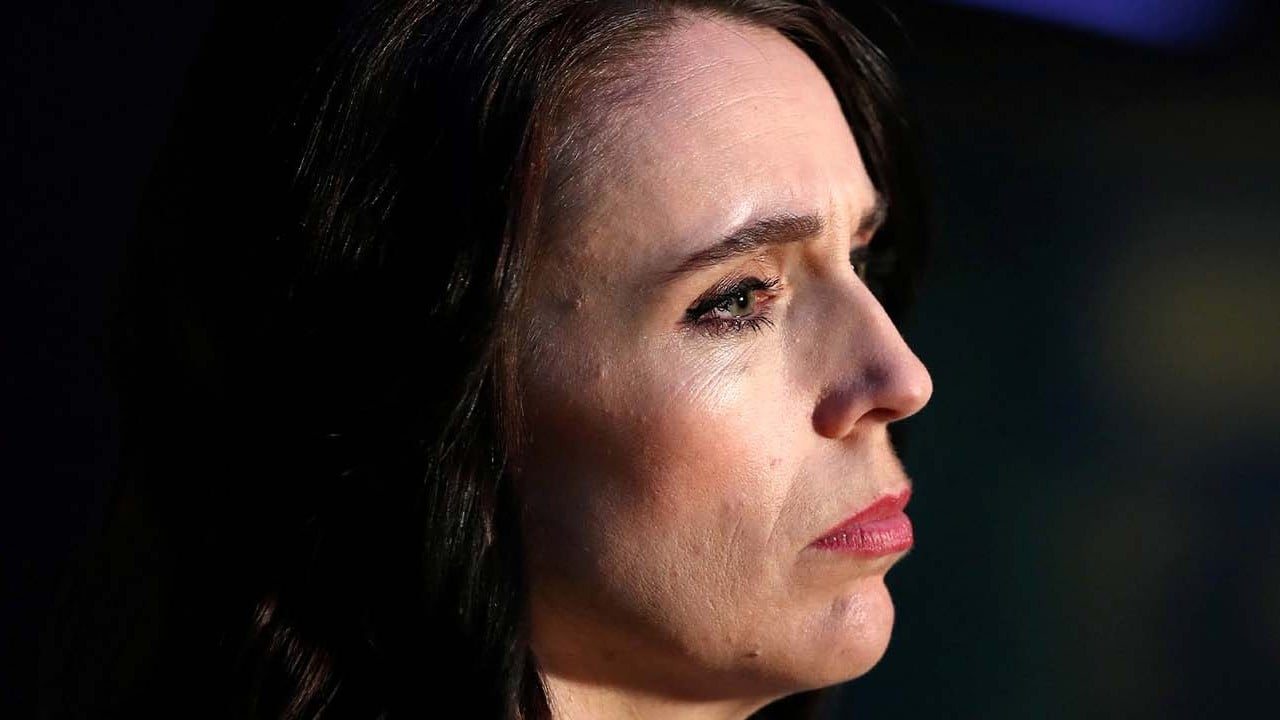

What Jacinda Ardern’s experience shows about women in leadership

- New Zealand’s former prime minister served as an inspiration to the next generation of women leaders – even in the face of unprecedented hate

- Her empathy, self-awareness and deft handling of crises showed the world that a strong, decisive leader can still be compassionate and kind

But even as Ardern became one of New Zealand’s most popular – and powerful – leaders in recent history, she received a level of abuse no other prime minister in the country had faced.

“The pressures on prime ministers are always great, but in this era of social media, clickbait, and 24/7 media cycles, Jacinda has faced a level of hatred and vitriol, which in my experience, is unprecedented in our country,” former New Zealand prime minister Helen Clark told reporters last week.

Ardern faced unprecedented hatred, ex-New Zealand leader says

An online hate tracker run by researchers at the University of Auckland found that some 93 per cent of more than 5,400 toxic messages targeting seven high-profile politicians from 2019 to 2022 were aimed at Ardern. She faced online vitriol at a rate “between 50 and 90 times higher” than any other high-profile figure in New Zealand, the study found.

She was also accused of having more style than substance, with the local press criticising a surge in spin doctors under her tenure that made it more challenging to hold to account what Ardern had promised would be the most “open and transparent” government New Zealand had ever seen.

Even Swedish environmentalist Greta Thunberg had a go at Ardern’s green policies, calling New Zealand’s bid to reduce 1 per cent of emissions by 2025 inadequate.

Scientists in New Zealand ‘potty train’ cows for climate benefits

Still, experts say Ardern has on the whole received more than her fair share of unfair treatment due to her gender. “Far too much of the criticism directed at her has been coloured by sexist and misogynistic attitudes,” observed leadership expert Suze Wilson from Massey University.

Some observers have argued Ardern jumped before she was pushed as fast-sliding opinion polls – amid high inflation and cost-of-living woes – sink Labour’s chances in the next election.

Ardern can exit with confidence that she practised what she preached: ‘A belief that you can be kind, but strong. Empathetic, but decisive. Optimistic, but focused.’

But on the other hand, her manner of bowing out shows the simplest acts can perhaps be the most subversive. Knowing when to quit – and having courage enough to admit there are others more suited for the job – is a trait that should arguably be encouraged among more leaders. It requires a level of self-awareness that has been in short supply in both workplaces and politics, with leaders often choosing to overstay their welcome because of a delusion that they are irreplaceable. In Ardern, the world has an example of a leader who shows that ego can take a back seat.

“Ardern demonstrated what power is and could be, and what it hasn’t been,” said Ziena Jalil, an independent director and strategic adviser in New Zealand who has researched political leaders’ brands. “She showed a new generation of women that they too can aspire to the highest offices regardless of gender and age, and without needing to conform to traditional, often more masculine, traits of leadership.”

Ageism in the workplace is a bigger obstacle for women than glass ceilings

Ardern smashed the glass ceiling in many ways, and she can exit with confidence that she practised what she preached: “A belief that you can be kind, but strong. Empathetic, but decisive. Optimistic, but focused.”

She leaves a legacy for young people navigating what it means to be a leader today as gender expectations continue to shift around the world. But Ardern’s experience also shows that for women, breaking barriers is just the first step on a long path towards the equal treatment of women in leadership and politics.