Scott Morrison’s stance on climate change is a ‘code red’ in itself

- The Australian prime minister pointed blame at China’s carbon footprint after the UN released a damning report on the effects of global warming

- His refusal to join the countries that have committed to net zero emissions comes as little surprise, given his record on climate issues

Most people, and most governments, would take what the UN has dubbed a “code red for humanity” as a clarion call for immediate action to bolster the increasingly fragile systems that support life on Earth. Most would consider the sequence of supposedly once-in-a-lifetime climate events that have occurred in rapid succession, from devastating wildfires in Australia and the United States to massive flooding in Germany, Belgium, and China.

Then again, most people are not Scott Morrison.

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of coal and gas, which together account for a quarter of its export income, or about A$120 billion (US$88 billion) a year. Coal has for years been ranked as Australia’s No 2 export behind iron ore, but its three biggest customers for the fuel – China, Japan, and South Korea – have all set zero-emissions targets, the latter two by 2050.

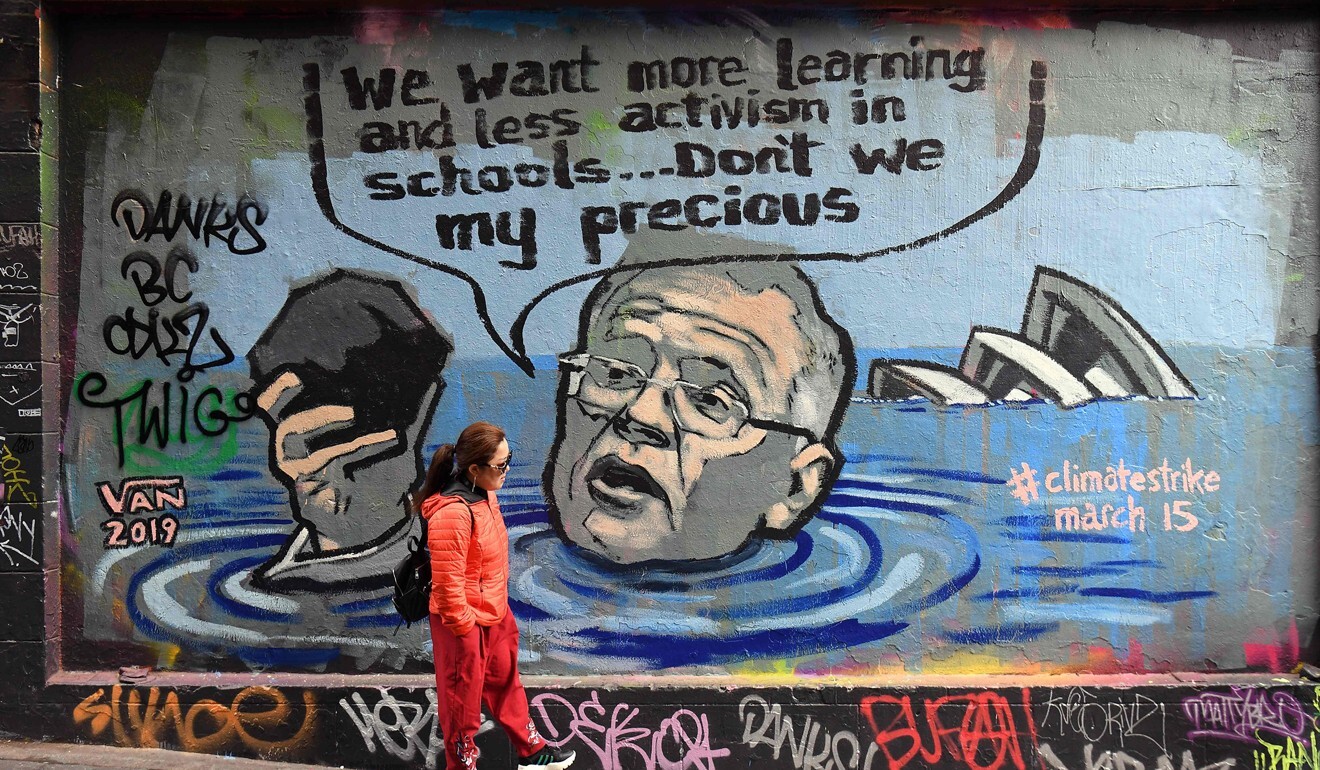

Two years previously, Morrison, Tony Abbott and Peter Dutton – respectively the current, former, and favourite to become prime minister – were caught joking about rising sea levels in the Pacific. A boom mic positioned above the three officials captured audio of them noting that attendees from Pacific Island nations were running late to a forum, with Dutton saying: “Time doesn’t mean anything when you’re, you know, about to have water lapping at your door.”

In words that are eerily familiar, the Australian delegation had insisted on removing from the forum’s official communique any references to coal, setting a limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius for global warming, or announcing a zero-emissions strategy by 2050 – in essence, imposing the political calculus of Morrison’s party upon countries at existential risk from climate change.

The planet’s climate looks likely to change much faster than Canberra’s stance on it

Even the Morrison administration’s handling of the Great Barrier Reef uses the same playbook. In June, an expert Unesco committee recommended that the reef be added to a list of World Heritage Sites that are “in danger”, an indictment that not enough had been done to protect it.

The reef has lost more than half its corals since 1995, according to an Australian Research Council report in October last year. The report attributed the main cause of coral death to climate change. Australia’s conservative government attributed the move to politics, given that China currently chairs Unesco.

After some frantic lobbying, Canberra succeeded in avoiding the downgrade, with a report on the reef’s status pushed back to 2022. If only this level of righteous fury had been aimed at actually dealing with damage the 2,300km natural wonder has already suffered, instead of outrage at a label indicating it was in dire need of help.

Australia in 2015 committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, with Morrison saying that any updates to this target will be revealed at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow later this year. But the prime minister as recently as January declared that coal mining will continue to generate wealth for the country for decades to come, despite calls to phase out fossil fuels – and despite reports in June that Australian coal burned overseas accounts for nearly twice its domestic emissions.

Perhaps the Morrison administration will pay closer attention to the threat of lost revenue, as global demand for coal lessens, than that of climate change. Perhaps later this year, Australia will join the countries that have already realised there is no time to waste when it comes to recalibrating targets, approaches and attitudes towards the environment. But while I have never hoped more to be wrong, the planet’s climate looks likely to change much faster than Canberra’s stance on it.