Anwar Ibrahim’s prophecy of power could come true at last. But for Malaysia, it might be better if it didn’t

- As the Malaysian democracy icon prepares to meet the country’s king on Tuesday, anticipation is growing that he might finally become PM

- History shows such an upset is possible, yet the compromises it would involve could dash any hopes of democratic reform and cause inequalities to stagnate

Self-fulfilling prophecies occur when something happens because one said it would, whereas their inverse – self-negating prophecies – are the polar opposite. Both are well-documented phenomena, and serve to show the power that imagination has to shape the world we live in, as it is the claim itself that alters reality, creating the context needed for the prophecy to happen.

Anwar’s plot to oust Malaysia PM Muhyiddin: Mahathir doubts it, Najib mocks it

Politicians everywhere depend on these sorts of phenomena to some degree, but they are particularly apparent in Malaysian politics, with Anwar giving us a brilliant demonstration.

Count and recount as many times as you like, Anwar does not have “the numbers” in parliament – his loyal coalition supporters like the Democratic Action Party and Amanah have been staying at a safe distance, since he apparently did not consult with them nor reveal to them his plans.

This is the reason he has not been able to give names, or a list of the supporters he claims to have. But the timing of his announcement was crucial in creating momentum that has allowed Anwar to influence reality and, perhaps, eventually obtain what he wants.

Remember, it was only a few short years ago that Mahathir prophesied his own reinvention from autocrat to democrat, which ended up getting him re-elected as prime minister.

01:34

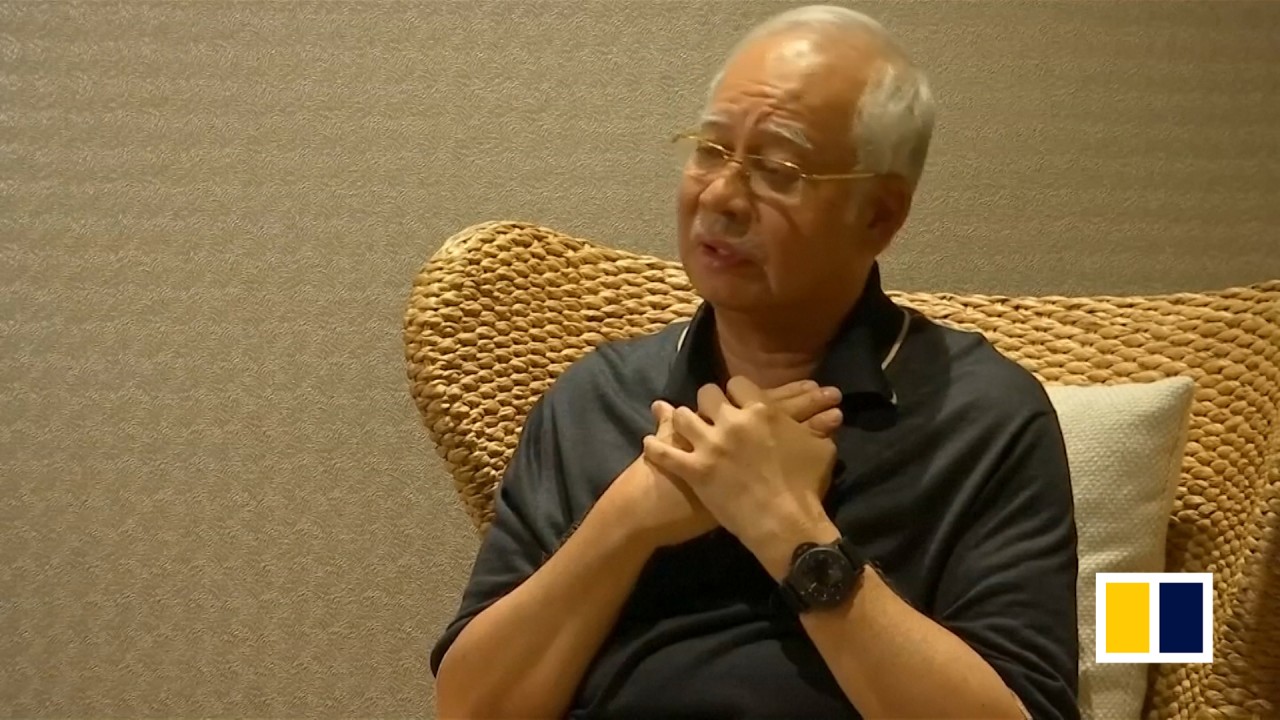

Former Malaysian PM Najib denies benefitting from 1MDB in exclusive interview

Mahathir’s first 22 years in power were tainted by authoritarian tendencies and the severe repression of the Reformasi movement, founded by Anwar. Yet two decades later, Mahathir made Reformasi his own, and became a champion of human rights and democracy – ideas he had criticised in the past as “Western”.

Today, Anwar is attempting a similar leap of faith – even if it implies compromising his democratic agenda by allying with the leaders of the United Malay National Organisation he once labelled “corrupt” and “kleptocrats”.

Yet an alliance between Najib, Zahid and Anwar could turn the tide of history for the Umno leaders, whose political fates are now intertwined with their legal predicament. Umno’s alliance with Bersatu, Muhyiddin’s party, has not been favourable for Najib, what with his July sentencing and another corruption trial set to resume on Friday.

In spite of the theoretical independence of the Malaysian judiciary, the courts’ decisions are highly political ones and a leadership change could create a more favourable political climate for leniency. Like Anwar did when put on trial for sodomy, Najib has maintained his innocence for years and accused the Mahathir government – which brought the charges – of conspiring against him. The truth here does not matter: this could well be another self-fulfilling prophecy.

The opposition lost another state, and handed the embattled prime minister a superficial victory, for even though Muhyiddin may appear to be in a position of strength, he is in fact vulnerable to pressure from within his own government – both from Umno and the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS).

Anwar’s announcement only added to the pressure, as many of Muhyiddin’s recent political decisions have put his ruling coalition to the test. Despite the key role Umno played in consolidating several victories for Muhyiddin, he has favoured members of his own party when it came time to appoint the new chief minister of Sabah, as well as the new state cabinet. The leadership of Umno is, understandably perhaps, not best pleased with its fragile ally and wants Malaysia’s voters to have their say. But for Muhyiddin, an early general election could well be the end of the road.

Since we are discussing prophecies, let’s use our imagination to anticipate what could happen on Tuesday – and deduce whether Anwar’s prophecy will be self-fulfilling or not.

Muhyiddin’s government and Malaysia’s fragile status quo can’t last

In the second scenario, Anwar’s attempts to harness the momentum created by his announcement were not enough to take him to the top. His manoeuvring influenced the Sabah election and destabilised the Muhyiddin government – sending tremors through the stock market as collateral damage, or perhaps by design.

The momentum also helped him raise funds while making promises to businessmen keen on getting closer to the man they believe might become prime minister in a matter of days.

But this time, again, Anwar does not have the numbers. The meeting with the king is followed by a dramatic speech and disappointment for his supporters. He explains away the flop by crafting another conspiracy story.

Whether or not Anwar’s prophecy turns out to be self-fulfilling, there is another prediction we can all look forward to watching unfold: Najib’s triumphant return to power, only this time as a democracy icon.

Sophie Lemière is a political anthropologist and Associate Researcher at the Collège de France’s Institut du Monde Contemporain in Paris. She is also Associate Researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand’s The History Workshop in Johannesburg, and Adjunct Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC.