US-China rivalry: it’s not a Cold War, but is conflict inevitable or avoidable?

- Neither Washington nor Beijing want conflict in the South China Sea, or over Taiwan or Hong Kong, says former Singapore ambassador Chan Heng Chee

- But in the absence of mutual trust, they will push their positions to the farthest limit, and Asean will be the site of keen strategic competition

The Trump administration is convinced China wants to offer an alternative model and shape a world antithetical to the values and interests of the US.

01:34

Trump ‘pleaded’ for China to help him get re-elected, writes former US adviser Bolton in new book

The US has been the hegemonic power for the past seven decades in Asia, providing a strong security and economic presence. The rise of China has been welcomed in Southeast Asia as both an opportunity and challenge. Although there are two US treaty allies in Asean – Thailand and the Philippines – they are less enduring allies for the US, unlike Japan or South Korea, as they were not driven by the same existential need for the treaties.

In recent years the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte has rebalanced its policy, pivoting to China. It continues to maintain US military ties, though it is ambivalent about whether to end the status of forces agreement (SOFA) with the US.

Are China and the US heading for a breather after months of sparring?

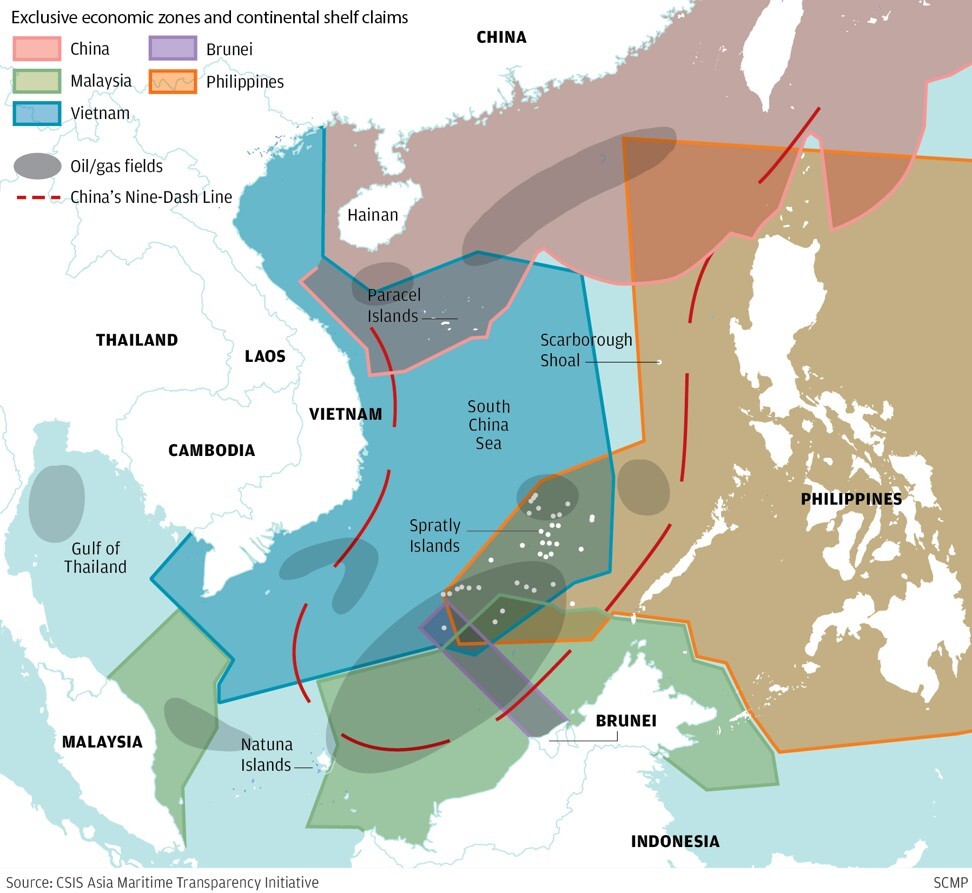

Although the parties in the South China Sea territorial dispute are China, Taiwan and the four Asean claimant states – the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam – the US is very much a player in the region and regarded by these countries as the only effective counterweight to China.

On behalf of the global superpower and the region’s dominant power, the US Navy Seventh fleet has defended freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait as well as the East China Sea. China’s nine-dash line claim – as well as its increased activism in reclamations and military build-up in the South China Sea – has not only alienated Asean claimants and increased anxiety in the region, it has sharply escalated the potential for conflict between the US and China.

The US Navy has responded with regular and robust freedom of navigation operations in the region’s waters, bringing the two navies into frequent confrontation. In October 2018, the USS Decatur, an American destroyer, nearly collided with a Chinese warship in the Spratly Islands.

The US and China are both party to the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, a 2014 agreement to reduce the chance of incidents and prevent escalation. Both sides expect encounters in the South China Sea to be the norm, but they are targeted to be below the level of provoking conflict.

Could US, China rivalry lead to war? History shows it might

Still, there is a possibility that a war could start by accident. Should that happen, one hopes what happened over the EP-3 incident in 2001 – when a US surveillance plane off the coast of China was shot at by a Chinese plane trying to chase it away – would be replayed. The plane landed on Hainan Island; delicate diplomacy ensued during the George W. Bush administration, when the neoconservative hawks were in charge. Fortunately, wise counsel from former president George H.W. Bush, former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft, and former secretary of state Colin Powell prevailed. The US and China stared each other in the face and decided it was not worth war.

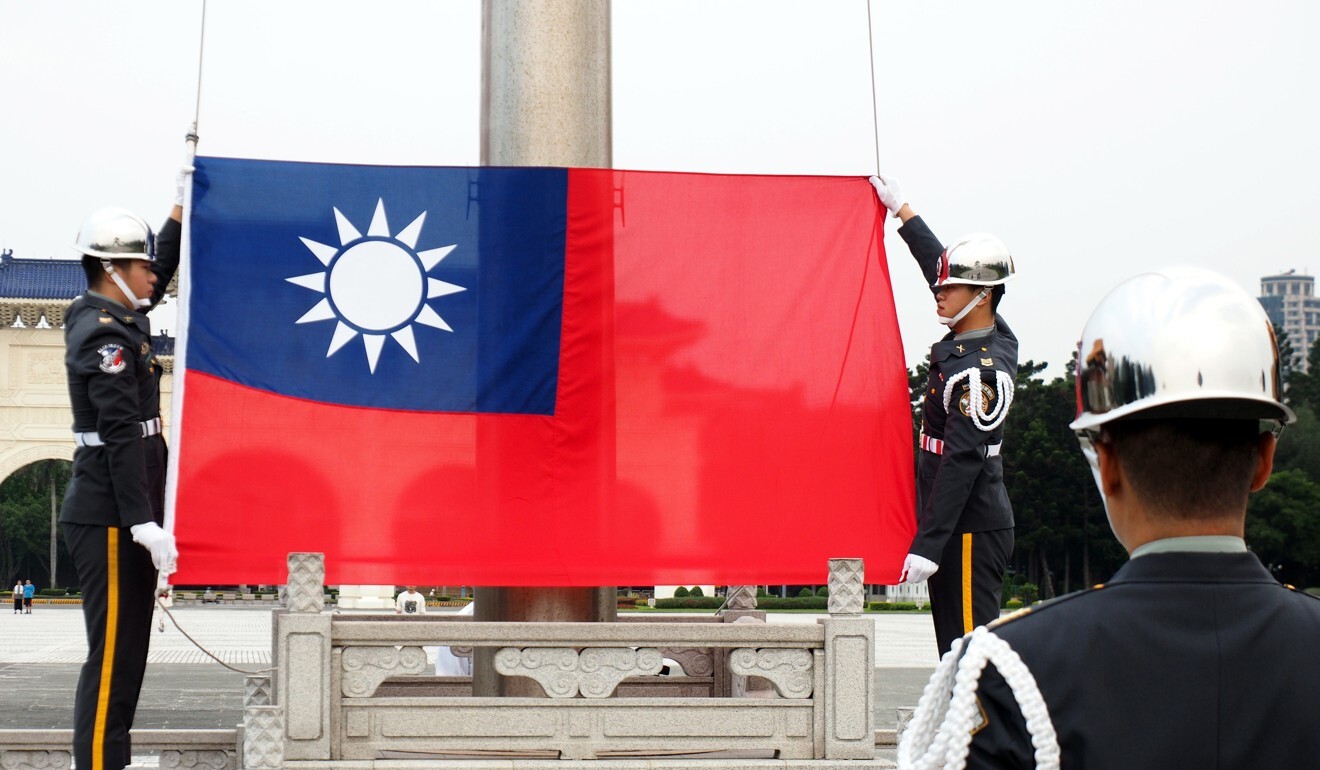

Could war between China and the US break out over Taiwan? For China, Taiwan is an enduring core interest. It has always regarded the reunification of Taiwan with the mainland as something of an inevitability. Taiwan, however, has long links with the US establishment in Congress, the State Department and the Pentagon.

There is also a Mutual Defence Treaty which obliges the US to help Taiwan in case of an attack from China. US defence allies in Asia such as Australia and Japan are bound by their defence agreements to fight alongside the US to support Taiwan in such an attack.

China’s zealous ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy highlights both Beijing’s power and insecurity

But in 2003, then president George W. Bush sent a clear message to Chen Shui-bian – Taiwan’s president at the time, who was pushing provocative tactics on the cross-strait issue – during the visit of China’s then premier Wen Jiabao to the US. Bush said: “We oppose any unilateral decision by either China or Taiwan to change the status quo. And the comments and actions made by the leader of Taiwan indicate he may be willing to make decisions unilaterally that change the status quo, which we oppose.”

Drawing this line helped to stabilise cross-strait relations for a number of years, but Trump’s White House has a different attitude on Taiwan which borders on ideological and could lead to stand-offs with China, resulting in rash responses from both sides. In January 2020, after the Taiwan elections, a US warship sailed through the Taiwan Strait. This was presumably a response to China sailing its Shandong aircraft carrier through the strait twice before the election. The Trump administration is openly helping Taiwan expand its diplomatic space, passing the TAIPEI (Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative) Act, which strengthens the scope of Washington-Taipei ties and promises to help Taiwan gain access to international organisations.

Tsai Ing-wen at her second inauguration did not refer to the 1992 consensus between Beijing and Taipei in her speech, and she maintained the past administration’s opposition to China using “one country, two systems” to resolve the dispute with Taiwan. “Cross-strait relations have reached a historical turning point,” she said. “Both sides have a duty to find a way to coexist over the long term and prevent the intensification of antagonism and differences.”

China is deeply suspicious that Tsai would be moving towards de jure independence. In his work report to the National People’s Congress in May, Premier Li Keqiang was noted to have dropped the word “peaceful” when mentioning “reunification”, which is the standard reference to Taiwan. This excited speculation that China would proceed to toughen its stance on Taiwan.

Asia shouldn’t underestimate America’s ability to counter China

At a later press conference, Li replied to a question from a Taiwanese newspaper by reiterating that China remained committed to the one-China principle and “firmly opposes Taiwan’s independence”. He also slipped in that Beijing would “continue to show maximum security and do our very utmost to promote peaceful reunification of China”.

While the word “peaceful” came back, I would not read it as China changing its stance from the work report, but that China is signalling that nothing is off the table. The Taiwan issue bears watching.

And now there is Hong Kong. The US government took the side of protesters with Congress passing the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act 2019. In 2020, with China’s introduction of the national security law to cover Hong Kong, the Trump administration will withdraw the special status Hong Kong currently enjoys with the United States.

Whether it is the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait or Hong Kong, neither the US nor China want a conflict with each other – for many reasons – but they will push their positions to the farthest limits. For China, Taiwan and Hong Kong are core interests and they have more recently defined the South China Sea as a core interest too. For the US, it is about credibility as the guarantor of security and living up to the role of the predominant regional power.

The main concern of the region is a conflict or war started by accident between the two powers.

Are we, however, in a second Cold War? Former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger, having lived through the original, in November 2019 said “we are at the foothills of a Cold War”. Australia’s former prime minister Kevin Rudd said this is “Cold War 1.5”.

I would say the tech war is on, with Chinese student and scientist visas denied as well for subjects relating to computer engineering, AI and biomedical sciences. We have a tech cold war. But economically, the US and its allies all want to participate in China’s growth market. The US cannot shut China out, nor will Europe and other countries join it to isolate China.

The Cold War had economic and military structures. Economically, it was separate orders. Militarily, the US and Soviet armies confronted each other head to head and toe to toe.

Economically, this is not happening in the US-China rivalry, for the reasons I mentioned. Militarily, I don’t see the US and China confronting each other now.

So, this is not a repeat of the US-Soviet Union Cold War. But middle-sized and smaller countries, including Singapore, will face the same pressure from both sides to make choices in this contestation.

This is an excerpt of a speech delivered during the 7th IPS-Nathan Lecture Series titled The US-China Rivalry: Inevitable War or Avoidable War?