New Zealand mass shooting: is any country safe from terrorism?

- Has social media, populist politics and xenophobia created a community of extremists like Christchurch massacre gunman? Paul Spoonley believes so

Parliament is a case in point, with white female Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, Maori Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters and seats reserved for Maori political representation. But that reputation has been called into question with the shootings in Christchurch, even though Ardern made it clear she rejected on behalf of the country the politics involved in the shooting.

The incident gained international media attention, not helped by the gunman’s use of online media to explain what he was doing and even show it, by live-streaming the massacre.

The incident raised a number of concerns, not only for New Zealand but liberal democracies around the world.

The first is the ability and willingness of security agencies to devote enough attention and resources to monitoring extremists, as they have done with some Muslim or political groups. But New Zealand police admitted the gunman was not on their watch list – or any in Australia, where he was born and lived until a few years ago.

New Zealand authorities have said they consider right-wing extremism a concern but the question is whether enough resources and attention are devoted to such groups or individuals. It is no small or cheap task but clearly not enough had been done.

The second is the role of social media. The gunman used various media to express his views and actions, but also published a “manifesto” – similar to Norwegian mass-murderer Anders Behring Breivik’s “2083: A European Declaration of Independence” – which demonises Muslims.

New Zealand has a permissive approach to speech and most tend to argue in favour of free speech over limitations on practically any speech. The argument is free speech is integral to democracies and healthy community debate – and that is true. But surely there should be a severity threshold beyond which speech is deemed hateful and against social cohesion.

This incident will highlight the way in which these ideas migrate around the globe and help mandate extremist beliefs. It raises a series of questions for me: who monitors and manages hate speech internationally? Should it be left to the online platforms themselves? Or should there be international protocols to identify and reduce risks to public safety?

New Zealand’s Muslims left shaken and fearful after mosque shooting

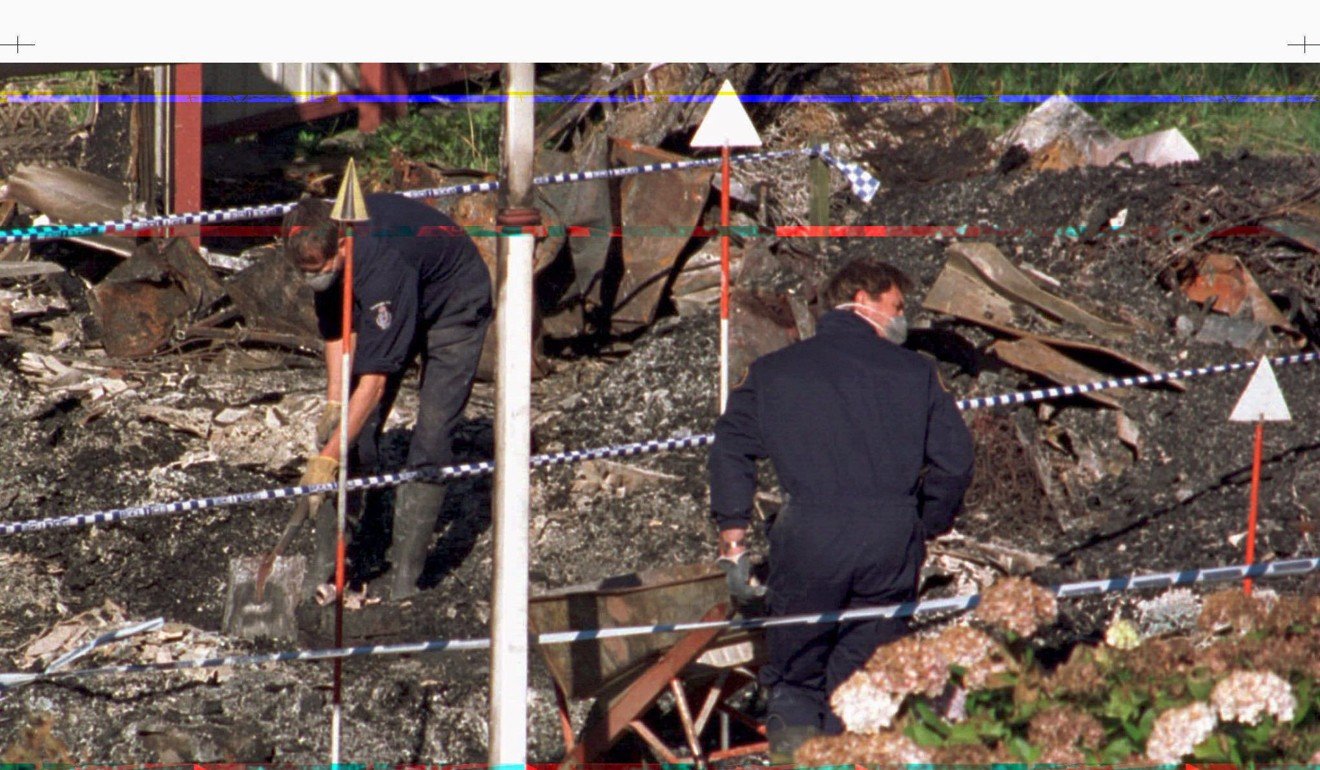

Domestically, the incident raises concerns about the ability to access firearms, especially high powered, rapid-fire guns. New Zealand has reasonable requirements for accessing guns and licensing the holder of a weapon. But the shooter obtained five guns, including two it would be difficult to justify ownership of in any local community. He also obtained a licence to own them. The prime minister has indicated that a review of gun ownership and safety is high on her agenda. As with changes to Australia’s gun laws after the Tasmanian mass shooting some time ago, it would be hard to argue against tightening New Zealand’s. Some will counter that tightening interferes with the rights of gun owners. These advocates, relatively small in number, will face a committed and concerned public.

New Zealand’s reputation for tolerance and safety has been irrevocably tarnished but it is the latest example of a shift to a form of political activism which has the ability to undermine core values and practices in western democracies. It is a hard lesson to learn that New Zealand, on the edge of the world, is not exempt from such contemporary political movements and ideologies.

Paul Spoonley is a distinguished professor at Massey University in New Zealand and pro vice-chancellor of its College of Humanities and Social Sciences