It’s no joke: the North Korean nuclear crisis could get Trump the Nobel Peace Prize

The US president’s unpredictability has pushed the peninsula to the brink of nuclear war, but it’s that same caprice that could save us all from Armageddon

To be clear, if the thinking in Washington today no longer excludes the idea of pre-emptive and, by likely implication, nuclear war with North Korea, then the prospect of near-term escalation in the domestic crisis surrounding the White House could soon yield to a “consolidation action” – in military form – by Trump that launches Asia and the world into a massive war.

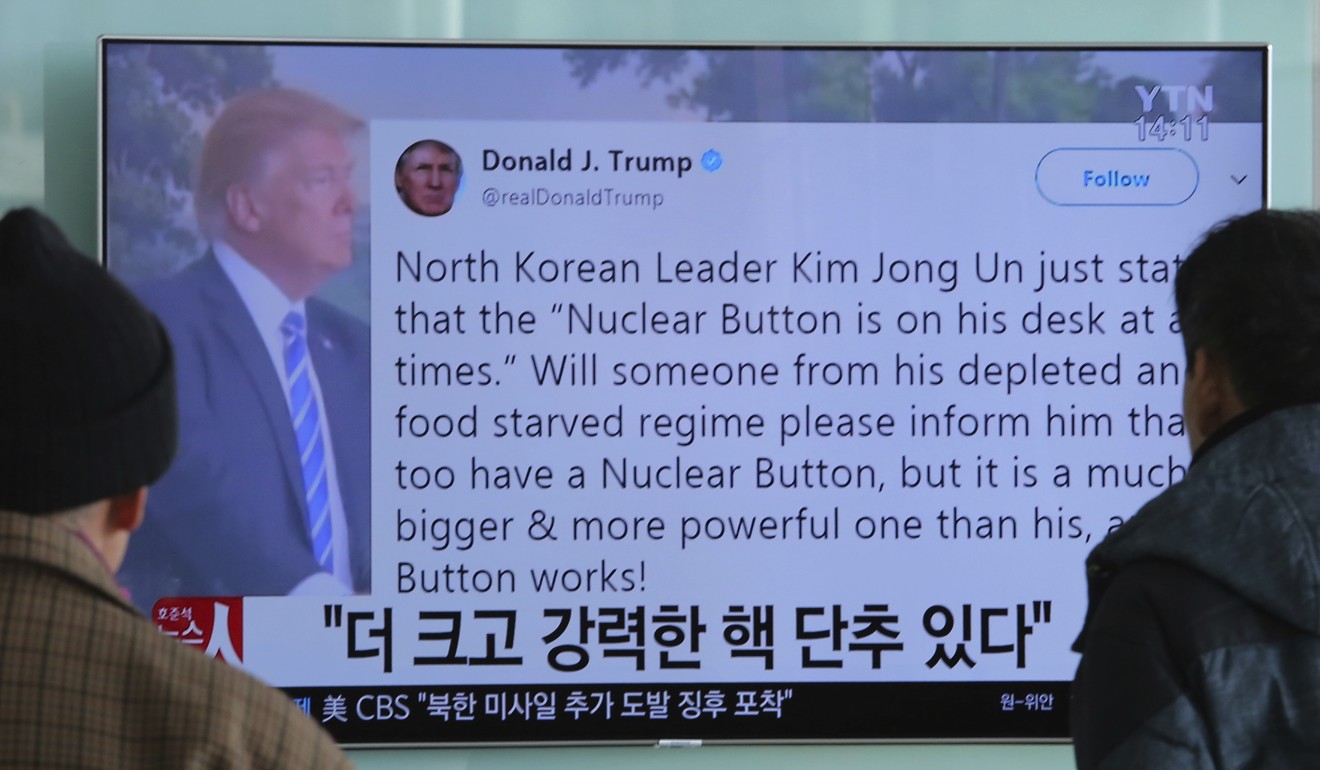

Trump’s big button to Thai penis whitening: hail the emperor, without his clothes

There are three crucial points that may be underappreciated in the present rhetorical and ideational hysteria that have led to this strange prologue to tragedy. First, from a North American perspective, war in general, and nuclear war in particular, continue to seem very “far” – a function of geographical good fortune that surely explains some of the American levity and obliviousness to proportionality in deliberating how and when to launch a war on another continent.

Watch: China prepares for a potential crisis in North Korea

Second, nuclear war over North Korea could well sound the death knell for the Chinese project in our time – that is, having finally recovered from the original destabilisation of the Opium Wars a century and a half ago, China could again be destabilised and suffer monumental political and economic regression.

Is China to blame for the North Korea crisis? The answer depends on who you ask

Third, nuclear war on the Korean peninsula will lead to other nuclear wars – given that nuclear powers such as China, Russia, Israel and India will not only become more loose in their standards for first use, but also because the nuclear powers will have lost trust among themselves in respect of nuclear restraint and judgment.

The good news is that the mad caprice that could lead to nuclear war in the coming year is the very same mad caprice that could give Trump the Nobel Peace Prize. This is not a joke. And while the present crisis in the Koreas appears, in my view, to have been largely manufactured or invented through poor American analytics and an improper appreciation and gaming of threat scenarios, the crisis has now manifestly assumed its own military, political and, critically, psychological momentum – one that is proving ever difficult to resist. And that is why the Nobel scenario offers a genuine alternative to cataclysm. But which Nobel Prize suggests itself in the context of the present nuclear tensions? And how would it be engineered?

The Nobel Peace Prize that saves the world from nuclear war requires that the US immediately change the terms of the desired endgame from the stated “denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula” to “reunification of the Koreas”. Denuclearisation to reunification is a radical shift, requiring a biblical degree of caprice.

Can North Korea cover up its brutal regime with lipstick diplomacy?

The path to the prize for Trump has two key steps. First, he must, as mentioned, declare the goal to be reunification rather than denuclearisation. This must come with a concrete, urgent timetable, requiring that a declaration of reunification be made jointly by Pyongyang and Seoul this year.

Second, as an immediate signal of goodwill, confidence-building and the intention to lead, support and partly fund the reunification project, Trump should open an American embassy in Pyongyang. This embassy would be temporary, pending the outcome of the reunification process. It should be accompanied by similar embassy openings by leading Western states – most importantly, Canada, Australia and France. (Germany, the United Kingdom and Sweden already have diplomatic missions to Pyongyang.)

Watch: How do South and North Korea communicate?

If Seoul, which has long prepared for this day, could be pressed to agree to immediate reunification in place of a potential war, this logic may be insufficiently compelling to Pyongyang. For Kim Jong-un, then, reunification must also be pitched in terms of an appeal to narcissism – to his potential glory not only as a Nobel Prize winner, but also as a hero and unifier in Korean history.

Don’t be confused by Trump’s mixed messages, US approach to North Korea is coherent … but scary

Evidently, the final look of a reunified Korea would be determined through intense negotiation and by the decisions and actions on the ground of millions of Koreans over the course of decades. The leadership of both Koreas should survive this reunification. And who knows where the capital will be?

If the original impulse and pressure for reunification should come from America, then the Chinese interest, typically associated with hostility to reunification – lest it lead to a powerful Korean neighbour at its doorstep and the demise of the Leninist model that is partly thought to legitimate Beijing’s rule itself – should also be updated. China certainly understands the prospect of its own terrible destabilisation in the event of a nuclear war on the Korean peninsular, let alone the far-from-inconceivable scenario of a direct military clash with the US. China is also increasingly frustrated with the caprices of North Korea – behaviour that is often well beyond Chinese control or influence.

Where China’s sense of vulnerability or its frustration with Pyongyang may not yet be sufficient in their own right to move Beijing to actively support reunification, it will be for Trump’s caprice and vaulting imagination to involve Beijing directly in shaping the reunification and, to be sure, to give Beijing a significant share of the economic and commercial opportunities that will arise from the huge reconstruction and modernisation work required in North Korea in particular.

Are US and China sincere partners in disarming North Korea?

If Trump is smart, then the engineering of a Korean reunification as a substitute for nuclear war could well prove the “deal of the century” that he has apparently been seeking on other continents. It is even possible that this united Korea will be non-nuclear. But if he is not smart, then he may well greenlight the bombing of North Korea soon after the conclusion of the Paralympic Games in late March. This would be perverse indeed, especially for a potential Nobel Prize winner. ■

Irvin Studin is editor-in-chief of Global Brief Magazine, and president of the Institute for 21st Century Questions (Toronto)