Judging empires: Was Japanese rule in Taiwan benevolent?

While imperialism may result in some benefits for those under rule, weighing up individual cases of good and bad misses a crucial point about the structures of empire

Taiwan’s politics, even today, is shaped by the memory of the years when Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists ruled the island during the cold war. The battle between the “mainlanders” who poured in at the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949 and the indigenous Taiwanese still resonates in today’s politics.

In contrast, one other relatively recent historical experience seems much less relevant: the period of Japanese colonial rule over Taiwan from 1895 to 1945. The younger generation hardly talk about those years. The older generation – and one has to be in one’s 80s or older to have any real memory of the period – often speak of the Japanese occupation with equanimity, even nostalgia.

Is Taiwan trying to erase links to mainland China, or forget a bloody past?

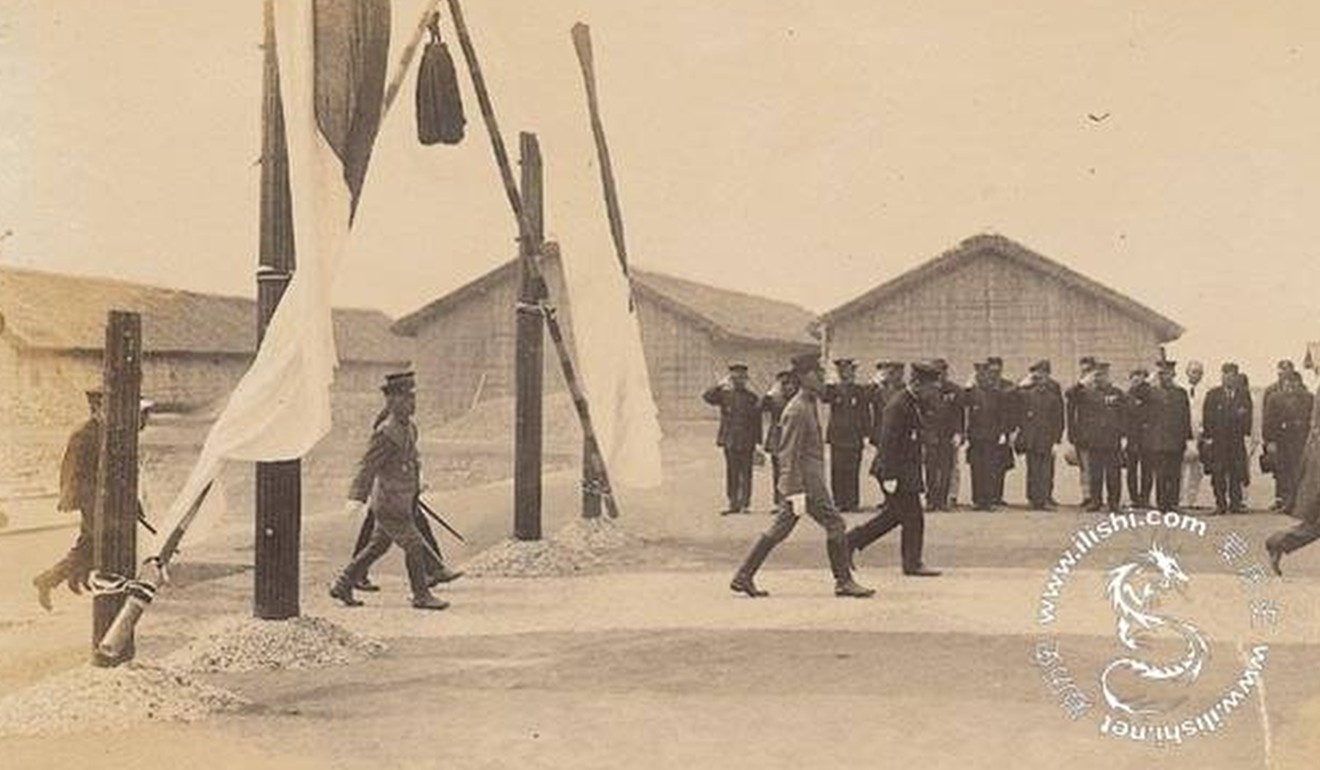

Former president of the Republic of China, Lee Teng-hui, who grew up in the colonial period, once famously claimed that he felt that Japanese was his first language. When they ruled Taiwan, its Japanese masters created a new Taiwan Chinese middle class which benefited from improvements in education, public health and infrastructure commissioned by their colonial rulers. Compared with the suppression of the native Taiwanese population by the Nationalists (for instance in the notorious 2.28 Incident of 1947, which led to the mass killing of many of the island’s indigenous intellectuals), Japanese rule seems quite benign.

This might seem useful material for the growing voices in recent years arguing for a more positive assessment of colonialism overall. Most of this analysis concentrates on the British Empire, rather than the Japanese or French. It argues, factually enough, that some unarguable good deeds were carried out by colonial states: for instance, the British Navy was fundamental in ending the slave trade. Overall, it argues that the best way to assess modern empires is to weigh the good and the bad and see how the balance works out.

Trump’s big button to Thai penis whitening: hail the emperor, without his clothes

Nobody fair-minded would deny that there were decent and positive actions carried out under imperial rule. But a balance-sheet approach, weighing up individual cases of good and bad, misses a crucial point about the structures of empire. These structures are always the same: they are about one set of people using power – ultimately, coercive, violent power – to control another set of people.

There may be such thing as a (relatively) benevolent empire; the last decades of British rule in Hong Kong would certainly qualify. But there is no such thing as an equal empire. An empire is not a nation-state, a political entity whose self-definition is of an equal, sovereign, citizen people (however flawed it might be in reality), nor is it a democracy.

Instead, an empire is necessarily a framework of rulers who have the ultimate say over the ruled, using violence where useful and arranging economic matters primarily to suit the imperialists, not their subjects. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be an empire. One of the finest novels on the ambiguities of imperialism, E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, captures this reality brilliantly. It ends with the English protagonist asking whether he can truly be friends with his Indian interlocutor: the latter replies, “We shall drive every blasted Englishman into the sea … and then you and I shall be friends.”

In other words, friendship is a quality that emerges between genuine equals.

An echo of colonial Britain in China’s boycott against South Korea

This doesn’t mean that there haven’t been positive sides of the imperial legacy. Imperial rule brought aspects of modernity to various societies; India’s railways are a product of British imperial rule, just as Korea’s chaebol have their origins in the zaibatsu industrial combines of Japanese colonialism. However, it doesn’t follow that imperial occupation was a necessary condition to change these societies. Japan was the only major Asian country (apart from Siam) to resist colonial occupation in the late 19th century.

Who gained the most from Hong Kong’s colonial era: Britain, China or the city?

Not coincidentally, Japan quickly became the most advanced country in the region, with its “Meiji restoration” giving it an advanced industrialised economy, new roads and railways, and a modern conscript army – not because of imperial occupation, but as a consequence of being free from it. Unlike those in India, Japan’s railways were laid down primarily for the benefit of its own people.

Early 20th century Japan became relatively rich. India, in the same period, stayed poor (and suffered famines, which, as Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has pointed out, happen in empires and dictatorships, but not democracies). Ironically, the main reason that mid-20th century Japan encountered disaster was its decision to form its own empire. Rather than strengthening its society at home, Japan decided to invade China, and wrote the death warrant for its pre-war society. A Japan that had stayed at home, getting rich, might have been even more prosperous.

Singapore and Hong Kong may be different, but there’s no debate on what the British did to India

The question of whether individual empires, or imperialists, can do good is easily answered. The South African Jan Christian Smuts believed in racial segregation; he was also a founder of the United Nations. Goto Shimpei, the colonial governor of Taiwan, believed that the Taiwanese were inferior to their Japanese masters; he also promoted education and development on the island for its indigenous people. An honest reckoning will give credit to many individual practitioners of empire for their positive contributions to history. But the honest reckoning has to ask how much that matters. The reason that empires were able to create those positive effects was that imperial powers had power – guns, money and powerful ideologies about racial and social superiority – that encouraged them to “civilise” other peoples. The first part of the reckoning may mitigate the second. It does not excuse it. ■

Rana Mitter is director of the University China Centre at the University of Oxford and author of ‘A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World’ and ‘China’s War with Japan, 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival’