80 years later: can China, Japan overcome Nanking Massacre’s legacy?

Memory of the mass killings in 1937 sits at the heart of disputes between Beijing and Tokyo today, but the issue goes beyond Chinese anger versus Japanese silence

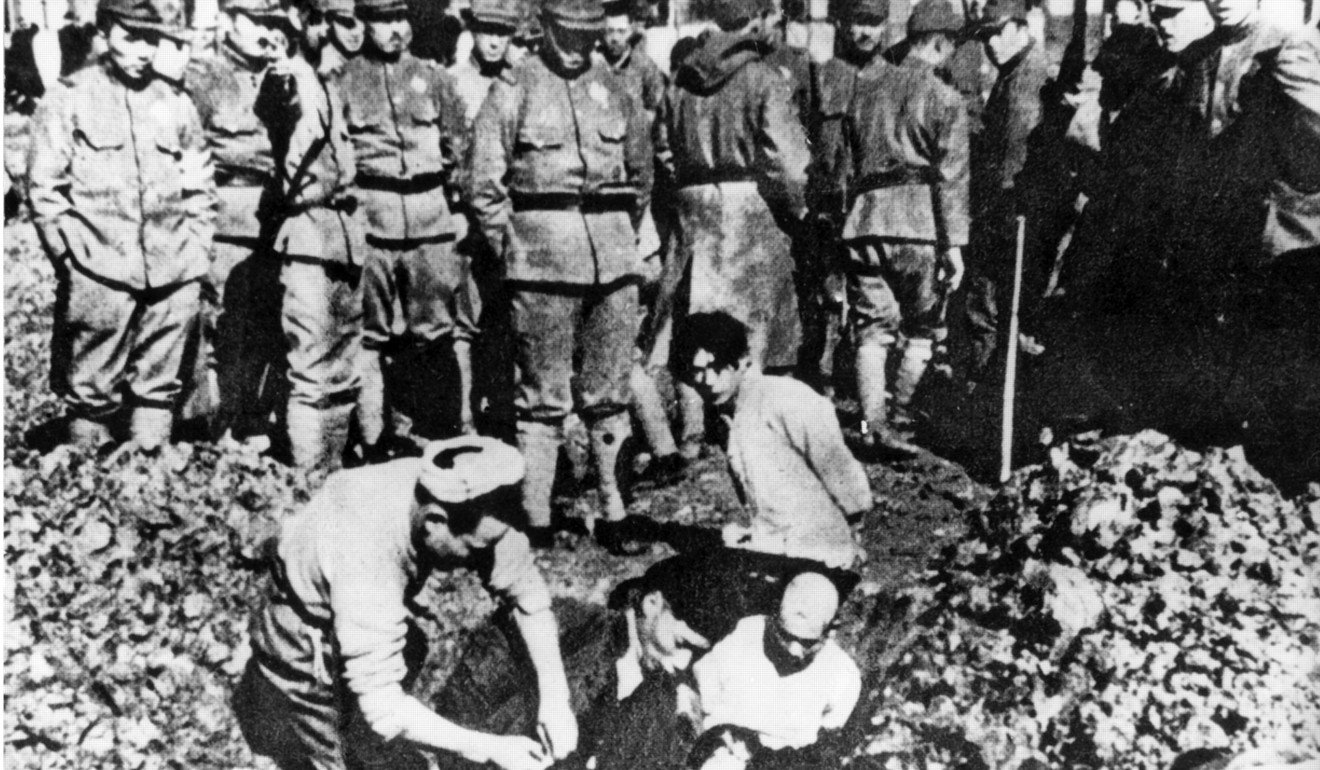

The city had been abandoned by Tang Shengzhi, the general charged with defending it to the death, the night before. On December 12, Tang himself had slipped away in a small boat while the city’s civilian population waited for the conquerors to enter. Few expected the Japanese to be gentle occupiers. But the scale of the savagery that the city saw was beyond imagination. The killing and sexual assault of thousands upon thousands of civilians would be remembered, using the city’s older English name, as “The Rape of Nanking”. Nowadays it is more frequently called the Nanking massacre.

Opinion: Can Asia handle parallel rise of strongmen in Japan and China?

Historians from China, Japan and the Western world have no doubts about the reality of the horror unleashed on the city. More difficult has been answering the question of why it happened. Reasons specific to the invasion itself played some role. The troops sent to the city as part of the Japanese Imperial Army were not the best troops that Tokyo had to offer. They had been told that the Chinese armies would crumble before them, but instead found themselves fighting lengthy, savage battles in places like Shanghai.

‘Pollution by tourism’: How Japan fell out of love with visitors from China and beyond

Memory of the massacre sits at the heart of disputes between China and Japan today. However, it is too simplistic to see the issue as purely one of Chinese anger versus Japanese silence. For a start, the Japanese role in exposing the massacre to the wider world was important. The Japanese journalist Honda Katsuichi was instrumental in publishing accounts of the massacre in the Japanese press in the early 1970s. There are still too many voices on Japan’s right who play down or even deny the events of December 1937. Yet the contributions of Japan’s progressive forces – historians, journalists, politicians – in acknowledging the shame of the Imperial Army’s actions have been an important part of moving towards reconciliation. Yet Japan’s public sphere has to make even greater efforts to look at the history of the massacre straight on. Even now, its aspirations for leadership in Asia depend in part on its ability to acknowledge the brutality of Japan’s pre-war past.

However, there is also a challenge for China. It is necessary, and right, to acknowledge the horrors committed against innocent Chinese during the killings of 1937-1938. It is also appropriate to commemorate the victims, as the memorial in Nanjing does in a sequence of wrenching statues placed on the approach to the building.

However, there must be no attempt to use the horrors of history to make simplistic claims about Japan today. Japan is a very different society from the one that gave rise to the atrocity: democratic, peaceful and seeking to strengthen multilateral ties in Asia.

What Shinzo Abe’s election win will mean for China-Japan relations

Eighty years on, the two major powers of East Asia should remember and mourn the Nanking massacre together, rather than remain divided over this most horrific of war crimes. ■

Rana Mitter is director of the University China Centre at the University of Oxford and author of ‘A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World’ and ‘China’s War with Japan, 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival’