Advertisement

China Briefing | Why a stronger Xi Jinping is taking a gentler approach in China’s foreign affairs

From THAAD to Singapore and the South China Sea, a series of abrupt changes of course may appear unconnected, but taken together suggest Beijing is recalibrating to a confident, more magnanimous style

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

With the conclusion last month of the Communist Party’s 19th congress, which made Xi Jinping China’s most powerful president since Mao Zedong, the general consensus among overseas analysts is that China’s foreign policy will become more confident, assertive, and muscular through its military build-up in places like the South China Sea and through economic schemes like the Belt and Road Initiative. In his report to the congress, Xi vowed that China would continue to seek a greater role in world affairs in a new era as it strides towards the global centre-stage.

In this context, it is interesting to see that, contrary to popular expectations, after securing a stronger mandate at the conference, Xi appears to have adopted a more conciliatory approach to foreign policy.

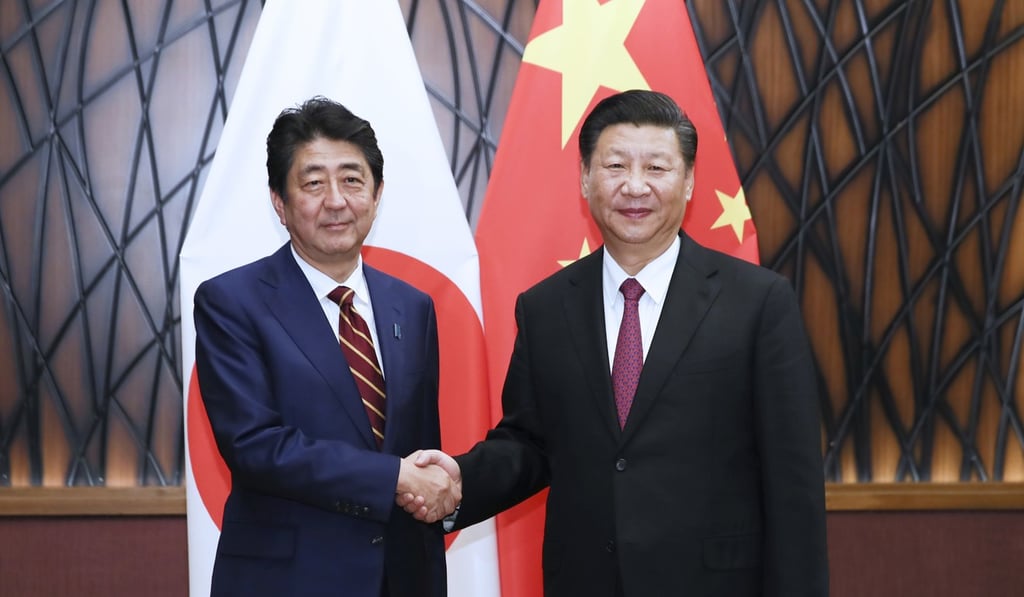

Last week, he chose Vietnam for his first foreign visit after the congress following heightened bilateral tensions over the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Recent media reports have suggested South Korean President Moon Jae-in could visit China as early as next month following more than a year of hostilities over the deployment of US anti-missile systems in South Korea, which China believes threaten its security. Even relations between China and Japan are on the mend as both Xi and Premier Li Keqiang met with Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe last week.

Advertisement

Those positive developments are in sharp contrast to China’s foreign policy quandary over the past year or so.

WATCH: What did Xi Jinping do during his first five-year term?

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x