Explainer | Can Thai separatists and Bangkok agree on peace in talks brokered by Malaysia?

- On January 11, the Barisan Revolusi Nasional and other Malay-Muslim separatist groups from Thailand’s southern provinces hope to seek a peace deal with Bangkok

- While Malaysia is a trusted party due to its success in mediating in similar conflicts in the Philippines, it faces some heat over its appointed facilitator

Why is there a separatist movement?

The provinces of Pattani, Songkhla, Yala and Narathiwat in southern Thailand were historically part of the Malay kingdom of Patani. But they were severed from their southern neighbours under a 1909 colonial-era agreement between Britain and Thailand that put Patani under the authority of Bangkok.

The 3 million Malay-Muslims in Thailand’s south are a minority in Thailand, whose 70 million people are predominantly Buddhist.

While many have adapted to life as Thai citizens – including adopting Thai names – many oppose what they view as the erasure of their Malay identity under Bangkok’s “Thaification” policy to assimilate all citizens of the kingdom into the dominant culture of central Thailand.

This includes the erasure of the Malay language in government schools in favour of Thai as the sole language of instruction.

While many dates have been cited as the “fall of Patani”, including one as far back as the 1700s, most groups cite the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 as the major date of Thai hegemony over the region, pointing out that the treaty was done between the two powers without any consultation with Patani leaders and its people.

Who are the main separatist groups?

There are several organisations involved in the southern Thailand separatist movement.

Mara Patani, an umbrella organisation of Malay-Muslim separatist fronts, led peace negotiations in 2015 with the government in Bangkok before being sidelined when Thai authorities switched to negotiating with Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) or the National Revolutionary Front in 2020, after reaching an agreement with the more influential group.

The move put paid to years of negotiation, with both sides forced to embark on confidence-building efforts to mend the breakdown in trust.

Deep South Watch, a local conflict-monitoring network, says 7,224 deaths and 13,427 injuries have been linked to violence arising from the conflict from 2004 to February 2021. Victims have included Malay-Muslims, Thai Buddhist civilians as well as Thai soldiers, police and rebel fighters.

While staying relatively dormant for decades since the start of nationalist movements in the 1950s, the region erupted in violence following the 2004 Tak Bai incident, where a protest over the arrest of six men led to the death of 85 people – seven shot by Thai police while 78 others suffocated in trucks while being transported to an army camp after being detained.

Violence has continued amid the pandemic, with six bombs detonated in Yala on the last day of 2021. The BRN claimed responsibility for the blasts, according to Thai authorities.

On December 13, three bombs went off along a railway track in Songkhla, injuring two railway workers and one passenger, and causing damages to the carriage.

The provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala are among the poorest in Thailand, with a GDP per capita of around US$2,000-4,000, below the national average of US$6,600, prompting many to leave for better economic opportunities in Malaysia.

Why is Malaysia involved in the peace process?

Malaysia began brokering peace between Bangkok and the separatists in 2013 under Thai Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, during which the “General Consensus on Peace Dialogue Process” pact was signed between Thailand’s National Security Council and the BRN, marking the first time both sides put ink to paper.

After the 2014 coup in Thailand led to the elected government being ousted for a second time in a decade, the BRN refused to participate in the peace process, saying the new government was filled with their long-time adversaries in the Thai armed forces.

But Malaysia’s presence at the negotiation table has also been awkward.

“Malaysia has been very proactive with Mindanao [in the Philippines], Aceh [in Indonesia] and Sri Lanka, but when it comes to Patani, it gets difficult,” said researcher Adrian Pereira, referring to how Kuala Lumpur was involved in resolving conflicts between rebels and the government in those places.

Even though Malaysia shares a common language, culture, history and religion with Patani and the southern Thai provinces, Kuala Lumpur is bound by its close bilateral ties with Bangkok, said Pereira, who is from the North-South Initiative, formed in Malaysia in 2011 to support the empowerment of Patani youth.

As a member of Asean, Malaysia also has to adhere to the bloc’s principle of non-intervention in member states’ internal affairs.

“The Asean spirit prohibits Malaysia’s intervention in the call for self-determination,” he said.

Pereira however stressed that the matter of self-determination was up to the Patani people themselves, and since it was a right enshrined in the United Nations charter, the question was not whether Malaysia supported it but how.

While there are pockets of academics and historians that support bringing Patani “back into the Malay world”, former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad in 2019 said he did not believe Thailand would allow the region to have autonomy or independence.

“We only want to find ways to end the unrest, [otherwise] it could lead to Thailand becoming hardline, and many more will die,” he told US news agency BenarNews in New York in an interview.

Despite that official stance, the Brussels-based International Crisis Group in a 2020 report noted that Malaysia was home to the separatist insurgents, making its position in the peace talks “awkward”.

“Malaysia’s role as de facto mediator is awkward: since the country is Thailand’s neighbour and home to many insurgents, some Thai officials regard it as an interested party,” it said.

One such Thai insurgent leader, who is now based in Malaysia, however said Kuala Lumpur’s success in mediating peace in the Philippines’ Mindanao in 2014 could portend similar achievements for southern Thailand.

“Similar situations in Aceh, Timor Leste and Mindanao were resolved, so why not with Patani?” said Abu Hafez Al-Hakim, a spokesman for Mara Patani.

Conflict expert Chanintira na Thalang, from Thailand’s Thammasat University, said Malaysia had a special position in resolving such delicate situations.

“While the both the Mindanao and Thai border disputes are in Muslim-majority areas governed by governments of a different ethnicity and religion, Malaysia, as a moderate Muslim country and fellow Asean member state, could bridge the gap between the conflicting parties,” she said.

Who is the Malaysian mediator?

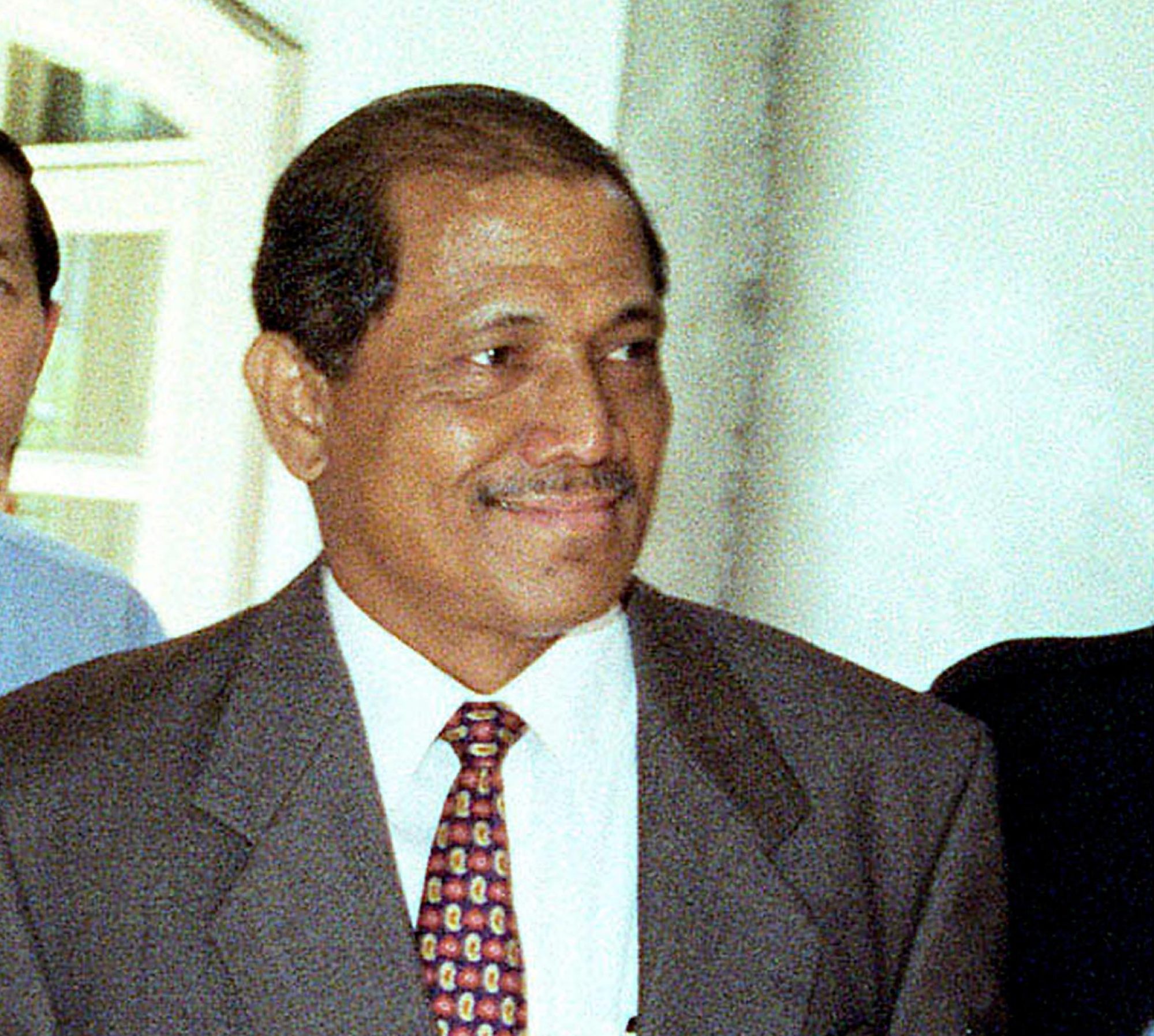

Rahim Noor, 78, is Malaysia’s appointed facilitator for the peace talks, though he is himself a controversial figure.

He came into the picture in August 2018 when then-prime minister Mahathir hand-picked him to replace ex-diplomat Ahmad Zamzamin Hashim, who was appointed by Mahathir’s disgraced predecessor Najib Razak.

Najib lost the general election earlier that year in the wake of the billion-dollar 1MDB corruption scandal.

In the past two years, Rahim has insisted that the peace talks should only take place face to face, a highly-placed source on the Malaysian side claimed.

“Both sides were keen on getting on with the talks, they already have a technical team sorting things out but Rahim refused to have it remotely,” according to the source.

Rahim, a former chief of the Malaysian police force, was instrumental in the 1989 peace settlement between Kuala Lumpur and communist insurgents who were launching attacks in Malaysia from their hideout in the forested border regions of Thailand.

Despite that success, he remains a controversial figure in Malaysian society after the top cop assaulted deposed deputy Malaysian prime minister Anwar Ibrahim in 1998 during an interrogation while under police custody, resulting in him appearing in court with a black eye.

Nurul Izzah, Anwar’s daughter and a member of parliament, in 2018 opposed Rahim’s appointment for the peace talks, referring to him as “a brutal assaulter of an innocent man”.

The appointment of the former top cop was also not well received by separatists in southern Thailand.

Saying that they had suffered under authority figures inclined to heavy-handed approaches on the Thai side, one leader said Rahim’s way of thinking was not aligned with what the separatists were trying to achieve. In fact, Rahim was the “biggest hurdle” to the peace process, he said.

The mediator “cannot be a police officer, it needs to be a diplomat. Their way of thinking is not the same. The police sometimes think like they are ‘cowboys’ coming in with guns blazing, including Rahim Noor. We’ve sat down with him, we know how he is like”, said the leader, who declined to be named.

What are expectations for a resolution?

Even with BRN at the negotiating table, a BRN leader told This Week in Asia the group would not lay down its arms just yet.

“We will not put aside our weapons. When will we put it aside? Later when there’s a ceasefire,” he said.

In April last year, BRN declared a ceasefire on humanitarian grounds following the outbreak of Covid-19. Recent attacks suggest that such arrangements are no longer in place.

Geopolitical strategy expert Azmi Hassan said however that the fact both sides were still eager to meet and talk after the hiatus, was a positive sign.

“The important thing is they both want to talk. And I attribute this to the mediator, Malaysia, which is trusted by both sides,” Azmi said.

If this round of talks in Kuala Lumpur succeeds in producing any outcomes, Azmi said the next big question was whether the decision negotiated by BRN could be accepted by the people in Patani.

“The big issue is whether the other group can accept BRN as their representative at the negotiation table,” he said.