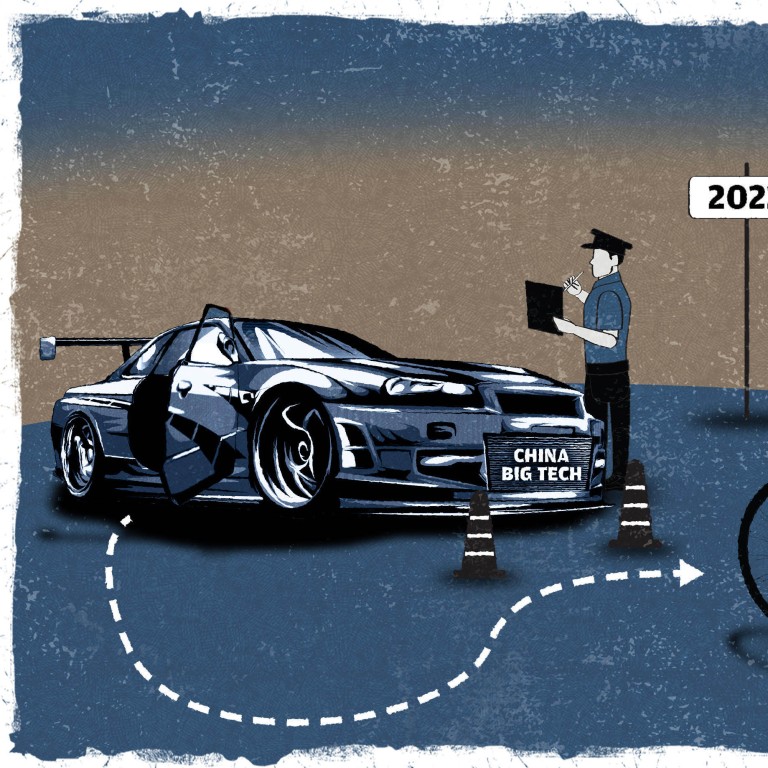

China 2021 tech crackdown: once seen as the golden ticket, Big Tech has shed jobs and lost its allure among the young

- The change of mood in China’s tech industry is tangible and sudden after a decade of exceptional growth

- Chinese users of internet services have also had to modify their behaviour in 2021 to comply with a barrage of new regulations

Xiang Zikui, a Shenzhen-based woman who works in the gaming division of one of China’s biggest internet companies, says she was shocked to hear about large-scale lay-offs at iQiyi, often dubbed China’s Netflix.

The Baidu-owned company, operating one of the country’s biggest video streaming platforms, reportedly started trimming more than 30 per cent of its workforce at some high-expense departments earlier this month, in a wave of lay-offs that is expected to continue through the Lunar New Year.

Short video giant Kuaishou Technology has also started to let go of employees who received low scores in performance reviews, the South China Morning Post reported earlier this month, citing three people familiar with the matter. Laid-off employees have been offered compensation based on the number of years they have served, plus one month’s salary, the people said.

While neither company was directly targeted by Beijing’s year-long crackdown on the country’s tech giants, the job cuts reflect a tougher overall environment for internet companies amid tighter regulations, more scrutiny of content and zero tolerance of monopolistic practices.

“The lay-offs may have more to do with the general industry trend,” said Xiang. “There are now strong regulations on many things including games, online ads and everything that involves privacy, which makes me feel like the industry may have hit a bottleneck.”

Baidu cuts staff from gaming unit amid regulatory crackdown, heavy losses

The change of mood in China’s tech industry is tangible and sudden after a decade of exceptional growth, blessed by lax regulation and easy funding. And for skilled tech workers from the country’s elite universities – who used to be fought over by Big Tech giants with offers of ever-higher salaries – the increased uncertainty is particularly harsh.

“These days there are voices around me saying that internet companies are no longer people’s first choice for jobs, and that some people would now prefer to work for state-owned companies or take civil service exams,” said Xiang. She added that Beijing’s ultimatum that game makers put in place anti-addiction mechanisms to protect kids had not affected her workplace too much though.

According to a survey conducted by Chinese job search platform Lagou that was reported by Chinese media, less than half of employees at the country’s internet companies are hopeful about getting a bonus at the end of this year. Another Lagou report published this month showed that in November, demand for talent from major internet companies shrank 26 per cent year on year.

While many Big Tech employees the Post spoke to said that their day-to-day work had not been affected too much by the government’s blizzard of regulatory action, some are re-examining their future career direction.

Feng Xing, a Chengdu-based software engineer working at a state-owned company and using a pseudonym to protect his identity, said that many of his colleagues who recently joined the company have come from major internet companies.

Under Beijing’s forceful clampdown, China’s tech giants fell in line

One contributing factor, according to Feng, is the fabled 35-year-old age ceiling in the internet industry, where people older than 35 are often shunned by employers and are at high risk of being laid off in cost-cutting rounds unless they have ascended to the ranks of senior management.

Some niche industries have seen a worse affected than others.

Kelly Huang, in her 30s and using a pseudonym to protect her identity, used to work at one of China’s top live-streaming platforms. She said that Beijing’s crackdown had mostly extinguished people’s desire to go into the live-streaming industry, a stark contrast to when she joined the company a few years ago when possibilities seemed infinite.

Live streaming has been repeatedly bashed by the Chinese government in recent months for allowing the dissemination of vulgar content, shady traffic numbers and reviews, and for opaque tax practices among its top influencers. Just this week, Huang Wei, known as Viya online, received a record fine of 1.34 billion yuan (US$210 million) from a local tax bureau for tax evasion, following less hefty fines on other live-streamers.

China’s tech crackdown: surveying the aftermath a year on

“I wouldn’t say that there has been a staff exodus at our company at this point. But it feels like everybody is just hanging on,” said Kelly Huang. “And the management’s focus has been on how to find pockets of new revenue and marginal growth to fill the void left by the revenue loss from areas which have now become heavily regulated.”

She said that declining prospects for the industry have savaged morale, which eventually led her to leave her job and join a hardware company.

But it is not just workers who have been affected by Beijing’s iron-fist approach to tech in 2021 – users of internet services have also had to modify their behaviour to comply with new regulations.

This year, Chinese regulators in August banned kids under 18 from playing video games for more than three hours a week, which accompanied a licence freeze for new video games in the country at around the same time. Beijing has proclaimed several times that it wants to prevent gaming addiction and promote positive content among the nation’s youth.

For Eason Shan, a 14-year-old teenager living in Zhejiang province, this has meant several lifestyle changes.

“After a certain period, I can’t play any more. Sometimes I can’t match my playtime with that of my classmates, so the gaming experience is worse,” said Shan, who plays Tencent Holdings’ popular mobile game Honor of Kings.

“Of course we were angry [when the policy was announced], we don’t want to accept it but we don’t have a choice,” he said.

Hangzhou fines top influencer Viya a record US$210 million for tax evasion

Of course, some kids have tried to game the system – employing a variety of workarounds such as using their parents’ accounts to bypass various gaming restrictions imposed by the government.

Evan Liang, a 14-year-old middle school student also using a pseudonym to protect his identity, said China’s tougher rules have not disrupted his gaming habits much. “Most kids have access to adult accounts … I do,” he said. “People have secretly registered adult accounts by stealing and using their parents’ national IDs.”

But Beijing has these practices in its sights too and summoned gaming companies on numerous occasions in 2021 to lay down the law on enforcing gaming restrictions and preventing such workarounds.

Beijing has also stepped up its scrutiny of online content – declaring that it must adhere to and promote positive cultural values.

Shanghai-based internet user Xiuli Zhou, also a pseudonym, said that in the past year, she felt that online content control has been tightened substantially.

An avid user of social media platform Douban, where netizens seek a liberal forum to gather and discuss films, books and current affairs, she has found it increasingly hard to communicate with others after the platform momentarily suspended a reply function in discussion groups.

In September, Douban suspended its reply function for a week due to “technical reasons”, although users speculated that it had done so in response to Beijing’s sweeping crackdown on social networks, online fan clubs and the entertainment industry at large.

Hong Kong IPOs hit by China’s regulatory crackdown, earnings misses

Earlier this month, Douban, along with 105 other apps, were also removed from app stores for alleged data privacy violations after being fined by regulators for the “unlawful release of information”.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the country’s powerful internet watchdog, said earlier this month that it had summoned and fined Weibo for repeated allowing “information forbidden by law and regulations,” and that it had punished the company a total of 44 times from January to November this year, with fines totalling 14.3 million yuan.

Zhou’s account on social media platform Weibo has also been banned from posting for no clear reason, she said.

“The result is I have to constantly self-censor myself,” Zhou said, adding that she also needs to use pinyin or romanised Mandarin to replace actual words, one of the many methods Chinese netizens use to try to get around online censorship, which is often done via key word filtering by platforms. “Which is a big hassle. Very annoying,” she said.

Censorship issues aside, Zhou said she thinks that many policies aimed at regulating the internet industry this year come from a good place and should enhance the industry’s development. But she added that more clarity is needed on red lines and what internet users can do to help themselves.

“That’s the thing with our national policies, they raise you up then hammer you down, they fiddle with you to make you develop at a stable pace,” said Feng, the software engineer at a state-owned company. “They don’t allow you to keep expanding.”